In a world where readily believable first-hand accounts from the frontlines of the war against terror are abound in the same pensive space that authors on this side of the line are trying to define, there is probably little that an author can do with fiction that non-fiction hasn’t already.

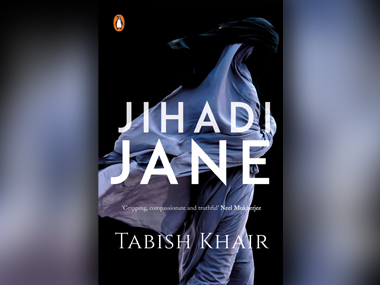

In other words, the war in Syria and the rise of the Islamic State have supplied enough narratives written along the tangent of documentation that even the most incisive of fiction is bound to stutter as it approaches the elusive inner self. Jihadi Jane by Indian-born writer Tabish Khair aims for the core, at a kinetic untangling of the stillborn question, the question that has in recent years eroded the anachronistic nature of probability in favour of the possibilities – why jihad? A query that has become so universal in appeal that it no longer specifies wherein the verity of the answers may lie, if anywhere at all. It could be religion, it could be the trauma of broken childhoods or it could simply be the exotic getaway from the ordinariness of contemplating life between the two.

Jihadi Jane is the story of two Muslim women, Jamilla and Ameena. Born and brought up in England, the two women live contrasting lives. While Jamilla, the narrator, is more reserved and in line with her religious upbringing, Ameena is the broker of the wild bunch, a quasi-rebel who finds in her little disagreements with the system the many reprieves that allow her to be part of one. But only just, because Ameena constantly struggles with her dysfunctional family, the sexism that her faith extends from and the racial profiling that Muslims across the country find themselves the subject of.

One, or perhaps the most important question that Khair would have had to answer in this fictional take is to try and explain to a reader why a person living in a prosperous third world country chooses to join the war in Syria. In that attempt Khair is largely successful although much of that success depends on the readers being familiar with the real-world situation. A reader approaching this book from behind an eclipse of information about the radicalisation of Islam in the Middle-East will most certainly find most of the book’s aphorisms unconvincing.

The two women find in Hejjiye, a matronly character, a woman apparently recruiting volunteers for the war in Syria over the internet. As far as journalistic supervision goes, this is as far as the insight of a non-fictional account would go. But a novel attempts to delve deeper, and understand the process and not the prospects. That is where, perhaps, Khair does most of his winning. One must consider, though, the contrast the story of a man on the same journey would bring to the writing. Here, gender is as much an issue, as is the provocation that radicals have come to sell.

A trick that Khair misses out is on the journey between England and Syria. Proclaimed as is in the book by Jamilla the tinctured details of the journey are omitted mostly because the journey itself is very simple on paper. There, though, is a human element to that journey, the irreparable path left behind and the many undecided, unwilled pauses that can only manifest in the manual, and the not so mechanical heart of a woman preparing to enter a war.

Both women enter Syria and henceforth begins the most predictable part of the book: the horrors of war, the stilted view of it in the head of the fanatics and in that view the many yearnings of our reserved protagonists. Ameena’s character seldom speaks in the book and we see her only through the eyes of the narrator. By the end there is a predictable turn of events as Ameena delivers the gong on the impending epiphany that may have most readers relieved, rather than curious about the blurring of her character.

Jihadi Jane is paced and structured to give the impression of a story told during a casual chat. It alights in places where the knowledge of speaking from a conflicted point of view is essential to separate the quality of prose from the reality that it must be attached to. Khair writes simply, and in most places with a word-of-mouth eccentricity, as only a documentarian or an interviewer might extract over a cup of coffee. There are some politically charged passages. For example, of Ameena’s mother, Jamilla says:

I can see the quandary she was in and sympathise with her: you cannot really discuss a moderate faith with someone who has an immoderate version of it

In perhaps an attempt to explain her confused self Ameena addresses the reader:

Divinity is divinity only to the extent that it exceeds the bounds of human understanding, you said. That was one of the statements that made me think of accosting you here. Well, perhaps, happiness is like that too: we cannot really understand the happiness of other people. Or their sorrow.

And:

You cannot imagine the bitterness all of this builds up in our souls. Sometimes I felt I would do anything to be free of all this, to be myself without being considered a monster or a curiosity.

Of Hassan’s (Ameena’s husband) agenda Jamilla says:

Hassan’s Islam was a do-it-yourself manual. . .for what? Ameena did not know: it was either for a living a certain kind of life or for gaining a certain kind of death, or perhaps both

Add to that these lines that centralise the nature of radical Islam in fairly layman terms:

The careerists win everywhere, believe me! Hassan’s fanaticism was a career to him. Killing was his corporate job. The apocalypse was how he planned to corner the market.

Perhaps, a restive, more ponderous approach to Jamilla’s psychology, and the induction of the image which is strangely missing from most of the book would have been welcome. The paucity of a take-away image renders us alien to the surroundings, the two-fold consequence of which is our inability to understand the people and the place that has made them. The question of the role of Islam in all of this goes unanswered as well – but that is in-line with most of reality. But then the interview-like narration of the book puts a cap on what can and cannot be done with the prose. Khair manages to keep it all together, sans his exploration of the jihadi in the woman, which is what makes this, as intriguing as it is challenging to write about.

The choice of gender adds to the quandary and in answering a severely more complicated question Khair can be seen at times struggling, for points of entry. That said, Jihadi Jane will probably ride the wind of its time, as it should, where the importance of the text might well be decided by what exists out of it. And that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Leave a reply