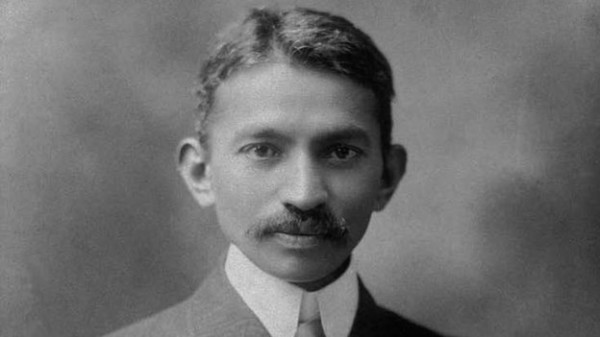

A photograph of Gandhi in South Africa taken in 1909

“I think it would be a good idea,” said Indian independence hero Mohandas Gandhi famously when asked by a British journalist about what he thought about modern civilisation.

But Gandhi was hardly a foe of the West. He counted three white men – Henry Salt, John Ruskin and Leo Tolstoy – as his mentors, wept when London was bombed during World War Two, and even hired Indians to fight in World War One.

He also spent nearly two decades – 1893 to 1914 – of his formative years in a foreign land – South Africa – where much of his time was spent as a lawyer and an activist.

Gandhi arrived in a deeply divided and inequitable South Africa, carved up into separate colonies, ruled by British expatriates and Afrikaners of Dutch descent. It was populated also by native Africans and Indian indentured labourers and professionals.

In this “strange scenario”, writes historian and author Ramachandra Guha, Gandhi acquired, honed and practised his four major callings – freedom fighter, social reformer, religious pluralist and prophet. He led protests against racial laws, reached out to different communities, forged friendships with dissident Jews and Christians and mobilised expatriate traders.

Guha has recently published Gandhi Before India, his magisterial new book on how South Africa changed the “earnest naive lawyer” to a “smart, sagacious and focused thinker-activist”. I spoke to him on how much Gandhi remained relevant in today’s world:

You write Gandhi’s ideas have survived. Can you give us some recent examples?

In India, the most important and influential of Gandhi’s ideas is one we affirm everyday without recognising it comes from him – our constitutional commitment to linguistic pluralism and diversity.

That we are not (or not yet) a Hindu Pakistan is also owed in some part to his legacy.

It is true that in their practice many politicians repudiate Gandhi.

Yet outside politics, in the sphere of social activism for example, he remains an inspiration.

The work of [social activists like] Ela Bhatt and Sewa or of Abhay and Rani Bang, is moderately well known; there are hundreds of such individuals and groups, who work away from the public gaze, in the fields of rural health care, women’s empowerment, environmental restoration, all inspired in lesser or greater degree by Gandhi.

But if Gandhi’s ideas have indeed survived, are they relevant in today’s age? If so, how?

In my view, four aspects of Gandhi’s legacy remain relevant, not just to India, but to the world.

First, non-violent resistance to unjust laws and/or authoritarian governments.

Second, the promotion of inter-faith understanding and religious tolerance.

Third, an economic model that does not rape or pillage nature.

Fourth, courtesy in public debate and transparency in one’s public dealings.

Gandhi, 1914, wearing white to mourn the deaths of Indian strikers killed in police firing

A curious testimony to Gandhi’s continuing relevance is the continuing vehemence of the attacks on him by radicals of left and right. Hindutvawadis [hardline Hindus] detest him – as some of the commentary on blogs and Twitter reveals. So do the Indian Maoists.

The British Marxist writer Perry Anderson, who in a 50-year-long career never previously showed any interest in India, has just penned a venomous attack on Gandhi – whose continuing worldwide influence he apparently cannot fathom (and certainly cannot understand).

How do you explain his glaring inconsistencies – saint and consummate politician, foe of the West and lack of bitterness against the ruling race, Hindu patriarch and upholder of human rights, practitioner of non-violence who hired Indians to serve in World War One? Or was he simply a confused man?

Gandhi lived a long life, wrote a great deal, and was actively involved in politics and social action for more than five decades.

It is therefore easy to quote Gandhi against himself (as it is with other prolific writers such as Winston Churchill and George Bernard Shaw).

On such matters as caste and gender equality, he gradually evolved, shedding conservative views for more progressive ones.

That said, there remain intellectual inconsistencies to be explained and personal fads (of diet, celibacy, etc) to be analysed – and Gandhi Before India and its sequel (still in the making) seek to do just that.

Do you think if Gandhi did not move out of the “conservative, static world” of his birthplace into a country still in the process of being made, he would not have become the great leader that he eventually did?

If Gandhi had succeeded as a lawyer in Rajkot or Bombay, we would not be having this conversation.

Had he lived in India, his clients would have been middle-class Hindus, and mostly Gujaratis at that.

He was saved from professional failure (and conservative habits and views) by the invitation from South Africa.

There, since his clients faced social discrimination from the white racist regime, he also began a parallel career as an activist.

Ironically, it was only in the diaspora that he came to appreciate the linguistic and religious heterogeneity of his own homeland.

Gandhi became a thinker and leader rather than a mere professional in South Africa; and it was here that he became more truly Indian as well.

You describe Gandhi’s South African campaigns as an early example of “diasporic nationalism”. Do you think diasporic nationalism has become rather controversial now as it is often identified with right-wing Indian nationalism?

Gandhi's wife Kasturba Gandhi with their children in 1901

The Indians in South Africa came from a variety of class backgrounds.

The struggles Gandhi led a hundred years ago first drew support from merchants, but later it was workers and hawkers who sustained it.

On the other hand, the Indian diaspora you refer to, based in the United States, is middle and upper class. And a solid source of support for Hindutva (Hinduness).

It is not clear whether economic privilege explains political reaction, however, or whether there are more complex psychological processes at work here.

You say Gandhi returned to India in 1915 fully formed and primed to carry out his different callings on a wider social and historical scale. At the same time, you say Gandhi around that time was essentially a community leader, who represented the interests of about 100,000 Indians in South Africa. So how did Gandhi transcend this?

Gandhi never intended to permanently stay overseas.

He came back in 1901 to try afresh at the Bombay Bar. Going back to South Africa a year later, he still hoped that when the rights of Indians in the Transvaal were secured he could return home.

In the event he stayed on till 1914, but for some time prior to that, had been urged by his closest friend Pranjivan Mehta to make a political career in India.

In retrospect, perhaps he (and we) were lucky that he stayed on as long as he did, since it allowed him to develop his social and political ideas, and emerge as an independent leader in his own right.

Leave a reply