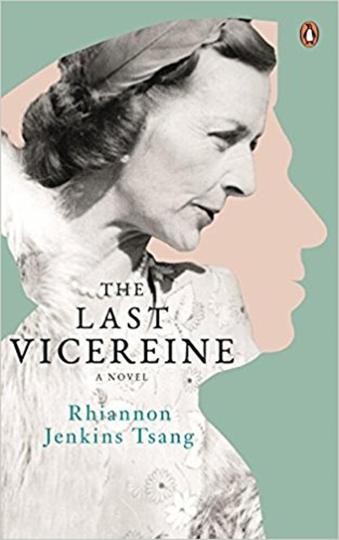

Review: The Last Vicereine by Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang

There are moments that define a country. Every incident, every event – however earth-shattering or even however worthless – is coloured by perception. For India this is so with Independence and the Partition, when great tragedy was conjoined with the euphoric final dissolution of colonial rule. The Last Vicereine by Rhiannon Jenkins Tsang is set in this turbulent time, the moment when a nation was born from centuries of struggle, divisions and upheavals.

Through the voice of a spectator and a friend, the novel follows Edwina Mountbatten, the last Vicereine of India, who along with her husband Lord Mountbatten oversaw the transition of power to Independent India and drew the lines that still have geo-political consequences. But this is merely a portion of the novel. A huge chunk of the story has fictionalized an explosive topic — the rumoured affair between Jawaharlal Nehru and Edwina.

The Last Vicereine shows Edwina’s empathy and role in relief efforts in the aftermath of Partition. It also displays her charm infused with a flamboyant ego and her unhappy marriage to Mountbatten. Despite all this, the novel doesn’t flutter beneath the surface of Edwina’s polished image. Perhaps this is because the story is being told by a narrator outside the mind of its subject. Sometimes a witnesses can present a picture of an individual, complete with their blemishes and positive points. That isn’t the case here. The voice of Pippi — a middle-aged British woman who lost her sons to war and husband to an ailment, and arrives in India as a special assistant to Edwina — overpowers the theme. Pippi’s steadfast attempt to distract herself from grief, and her exploration of Lutyen’s Delhi and of the political power circle takes up most of the space. The Vicereine is lost somewhere in between her virtues and a misplaced love.

Indians are apt to read this novel with some skepticism. The itch to gauge how the Western world thought of us, and still does is part of our colonial baggage, one of the complexities that comes with being born in a nation that belonged to the Commonwealth. About this, there’s good news and bad.

Let’s begin at the heart of darkness. All the thoroughly-sketched Indians in the novel have Western ideals or have had a Western education. Nehru and Pippi’s love interest, Dr Hari, are both intellectuals who have glimpsed the developed world. Minor characters like Zamurad Khan, an employee of the Viceroy’s House, are simply obedient followers of the British. It’s telling that common Indians who suffered the most in the aftermath of Independence are absent through most of the story. They are visible (literally) from an aerial view that dehumanises them, making them an embodiment of poverty, rioting and abuse. The reader cannot possibly sympathise with others like the constable, who brutally slits the throat of a stray dog.

The novel – much like modern Britain opting for Brexit because it fears foreigners will swamp its culture and values – omits to emphasize that colonial rule wasn’t harmless. Not a single British character, including a white reporter sniffing for scandal, is reprehensible. This is a feat for a whitewashed tale of Partition about Empire withdrawing from the land it plundered.

Still, there’s some light. The author ’s choices aren’t intentional and there’s simply no spite in evidence. Because why would Pippi and Edwina’s meeting with Gandhi exalt the bespectacled leader to an almost God-like figure who, through the humble act of weaving, provides solace to the two troubled souls? There are no easy answers with this novel. There are no sides to pick. The Last Vicereine is a lot like the simultaneous occurrence of Independence and Partition. It’s bittersweet.

Leave a reply