Although NGOs help those in need, there are over two million NGOs in India and many of them don’t really do what they claim

Greenpeace claim that this is a crackdown on dissent from potential ‘disruptors of the narrative’

Sewa UK admit that honest NGOs are affected, but believe that Modi is doing this for the right reason

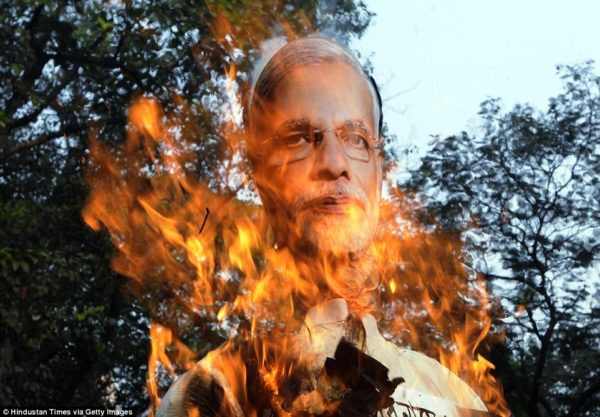

In his first two years in office we have seen much of Prime Minister Modi the statesman, charming (and enthusiastically hugging) the various world and industry leaders to arrive on India’s shores.

Internally he boasts a staggering 69% approval rating and his hastily arranged demonetisation measures seem to have actually boosted his popularity, despite the massive upheaval they’ve caused.

Added to his so-called ‘surgical strike’ against alleged Pakistani-backed militants on the de facto India-Pakistan border, Modi has made for himself a fully portable and powerful election hammer to help party members pound out the BJP ethos in poll-bound states across the country.

If present popularity is anything to go by, it is looking increasingly likely that he will be re-elected in 2019.

Although in the years since his election there have been flashes of the ‘Hindu supremacism’ and the rising tide of sectarian hatred promised by swathes of the western media, no single incident has been so sufficiently alarming as to deter a leader like Prime Minister Theresa May from visiting India cap-in-hand during the first round of Britain’s trade talks post-Brexit.

However, in Modi’s dealing with NGOs it would appear that we catch a glimpse of the leader who, it was argued by the Guardian, would struggle to find a balance in his character between political pragmatism and ‘the extremist ideology with which he has been associated since he was a young man’.

Despite all the good NGOs do in quite varied fields ranging from direct disaster relief (seen during the 2015 Chennai floods) to instances of children born with HIV denied an education – the BJP’s hatred for NGOs can be loosely broken down into a number of quite obvious reasons.

Firstly, the dissent from well-oiled self-funded PR machines with a human or environmental cause is believed to be curtailing India’s staggering economic growth.

Indeed the leaked intelligence report in 2015 claimed that groups like Greenpeace were damaging the country’s economy by campaigning against key development projects.

This in turn has led to the government pursuing bureaucratic solutions to solve human problems with the use of the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act withdrawing licenses so the NGOs cannot receive overseas donations, effectively strangling them.

As we’ve seen recently, the NGOs cannot appeal the withdrawal, nor is there a means to seek an explanation.

Secondly, there are over two million NGOs in India, and many of them don’t really do what they say on the tin. Corruption is rife. The large sums of money being thrown around, the lack of transparency and accountability as to where this money is being used has led to a great deal of mistrust.

So for every highly-efficient, globally-known NGO helping those in need, there are a number of NGOs whose operations are less transparent, and whose aims fall around the collection and spending of others people’s money.

But even so, why hate the help? It’s still not obvious why a leader elected to look after the poorest, most vulnerable people would choose to sever this lifeline.

According to Ravi Chellam, Executive Director for Greenpeace in India, ‘This is not a specifically Indian issue’ but rather a part and parcel of a general global crackdown from conservative governments seeking to decrease the scope for civil society.

‘I don’t think this issue is uniquely Indian, or even uniquely a BJP, Narendra Modi problem’ he says. ‘If you look at the global scenario with countries like the Philippines and the USA – what we are seeing personality politics with guys being elected with anti-liberal views and actually being quite proud about it. ‘They flaunt their views and there’s absolutely no shame or denial that’s what they are.

For Greenpeace and Chellam, this crackdown on dissent starts with the biggest players in the market:

‘Modi is attacking NGOs that people see as independent and credible; knowledgeable about certain specific issues, and potential disruptors of the narrative that these people want to convey.’

So, going back to the leaked intelligence report, is this about India’s economic growth? Perhaps, but Chellam disagrees with this oft-repeated idea of economic ‘growth’ in India:

‘If we fall into the trap of calling things like coal mining a ”growth” area we’re letting it be defined by economists who have a fairly narrow perspective. ‘Growth that results in a million premature deaths in not growth.

‘It’s like saying let’s have a pandemic so that people pay more for medicine and in that sector the economy grows!’

Who hates the help?

But when NGOs have a human cause – suffering, dying, marginalised people – added to a well-oiled PR machine and a source of funding, it’s not obvious why the Indian government would feel that this is a fight worth fighting.

But in India it often appears like he has the backing of his people.

The best summary of why ordinary, honest Indians follow their political leaders in a deep mistrust of NGOs is perhaps summarized best by a young man from West Bengal writing on the popular question-answer site Quora:

The young man exemplifies this peculiar mythology of mistrust in India, and according to Dr Nikita Sud Associate Professor of Development Studies at Oxford University, this mistrust is a large part of what brought Modi and the BJP to power in the first place.

‘The current government came to power with 31% of the vote,’ Sud says.

‘Those among the other two thirds of the country who did not vote for the ruling alliance might appreciate and understand what NGOs like Greenpeace and Lawyers Action Group do. But they are not the kind of people the government expects to rally behind them and support this rhetoric that NGOs are anti-national and must be put in their place.

‘The people that the government is hoping will support them in their fight against the NGOs lean to a suspicion of liberal, secular NGOs that talk about Human Rights and ostensibly give India a bad name. To many bhakts, or Modi followers, these NGOs are simply anti-national.

‘It makes sense for them to attack the very people that the rest of us see as the ”good guys”.’

Dodgy NGOs?

Dr Sud does sympathise with criticism of India’s disproportionate number of NGOs and the lack of transparency with which they often operate.

‘There is a big question about accountability. If you’re a company or a business you are accountable to your shareholders, if you are a government you are accountable to your electorate, but if you are an NGO there is a big question mark about who you are accountable to.

‘So if you are a big NGO like Oxfam you have built an accountability mechanism where the people who send £2 a month get regular updates about how their money was spent. For most of the 2 million NGOs in India that self-imposed mechanism for accountability does not exist.’

In short there’s not yet a good way to determine if an NGO is doing what it set out to do.

Bharat Vadukul of Sewa UK has his own stories to tell of India and those organisations he describes as ‘unscrupulous’ NGOs.

‘There are a lot of NGOs that make big claims about the work they purport to do, and the lives they save, but when you look at it closely – sometimes it is very hard to verify. Often what they’re saying and what they’re doing are two very different things.’

Bharat goes on to say, ‘I was over in India a few weeks ago and heard about the closing of one particular NGO that made it into the local press, but when you actually spoke to people about them it was obvious that what the work they reported and the work they actually did were two very different things.

In another incident he adds, ‘what happens immediately after a disaster in India (i.e Gujarat earthquake) we get a number of what we call ‘banner’ organisations cropping up.

‘They create a banner, a website, a name and an appeal with the promise to do all this great work.

‘But on one particular occasion one of these local groups in Gujarat started a campaign to help those suffering, and then immediately bought two 4x4s from the money that was collected for those in need.

‘They claimed that they needed these to get to the areas affected but as the relief mission went on it was obvious that the amount of work they did, didn’t justify the amount of money they had collected.’

Good NGOs or bad NGOs: Where to draw the line?

Sewa UK is a charity organisation and a splinter of the Sewa International group based in Delhi.

At present they are working on building schools and centres for people with disabilities and obviously continue to support long term rehabitation efforts after the upheaval in Jammu & Kashmir.

When asked about Sewa’s link to the RSS (the BJP’s ideological mentor of which Modi was once a member) Bharat says there is a ‘loose link’ with the RSS but everybody involved in Sewa in terms of running the organisation and in the background believes that humanitarian aid doesn’t stop at the point of creed, colour or caste.

‘Emergency aid goes to anybody that needs it, and that is a part of our Hindu scriptures.’

So does Modi’s clampdown affect both good and bad NGOs?

According to Bharat – ‘Yes’.

He adds, ‘Once the net is cast some of the good organisations get drawn in. When you are working hard and you’re struggling with a lot of things, you’re trying to help people and deliver on projects the emotions run high, especially when you’re being painted with the brush saying that you’re the same as all the unscrupulous NGOs – that’s frustrating.

‘But we believe that the Indian government is doing this for the right reason, however the way they’re doing it is unfortunately dragging good people in by association.’

Leave a reply