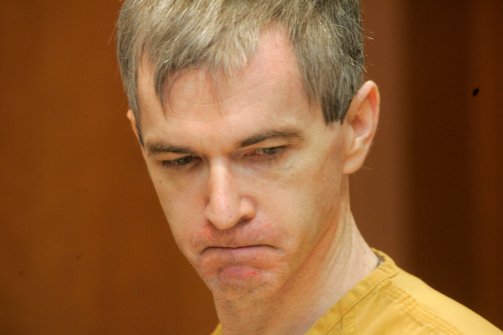

For 16 years, Charles Cullen kept killing his patients while his employers preferred not to notice. Lizzie Crocker on the new book that tells his story.

No one will ever know how many patients Charles Cullen murdered over the course of his 16-year career as a night nurse.

From 1987 until 2003, the man who may be the most prolific serial killer in American history was the subject of dozens of complaints and disciplinary citations, a handful of police investigations, up to 20 suicide attempts, and several lockdowns in a psychiatric ward. Many of his supervisors and colleagues were aware of his dangerous and unethical practices, but his professional résumé remained untainted as hospitals sent him with glowing references to become someone else’s problem. He worked at nine hospitals in total, murdering an unknown but large number of people—as many as 400 patients—with toxic intravenous injections.

Now, author Charles Graeber has compiled the full story in The Good Nurse. Out Monday, the true-crime thriller reveals as much about how hospitals’ systemic failings and unethical policies protected Cullen as it does about the serial killer himself.

The media dubbed Cullen “the Angel of Death”—a nickname he relished—when he was finally arrested in 2003. He then was convicted and sentenced to 100 years in prison. Raised Catholic, Cullen had always viewed himself as a martyr, like the namesake apostle of Saint Barnabas Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, where he began killing patients with insulin overdoses in the early ’90s. He later injected patients with high levels of digoxin, a deadly drug used to treat congestive heart failure.

Cullen is not the first serial killer in the medical profession. In 2000 a British doctor named Harold Shipman was convicted of murdering 15 patients (though an investigation revealed he killed hundreds more) and sentenced to life in prison. This year a Brazilian doctor, Virginia Soares de Souza, has been charged with murdering seven patients, though authorities warn that she also had hundreds of victims.

What makes these crimes particularly chilling is that they were committed in the very institutions we entrust our lives to. A hospital letting a murderer work freely is perhaps even more chilling than other instances of institutions—like the Catholic Church or Penn State—protecting themselves rather than the people they serve. Cullen may have been brought to justice, but the hospitals where he worked got away with murder.

In The Good Nurse, Graeber documents the numerous times hospitals decided not to bring in the police to look into unnatural deaths they had linked to Cullen. Instead they performed flawed if not perfunctory internal investigations that resulted in inconclusive evidence—and then let him leave with a clean slate. Desperate for night-shift staffers, prospective new employers ignored red flags from Cullen’s past.

The unpopular graveyard shifts made it that much easier for Cullen to satisfy his compulsion to kill, and when hospital insiders suspected or accused him of malpractice, he enjoyed the attention, reveling in their inability to stop him.

While Graeber presents Cullen as not entirely incapable of feeling or empathy (he didn’t want to disappoint his children, doesn’t want them to view him as a monster now, and strived to maintain casual friendships with other nurses), he still lacks the conscience to differentiate between right and wrong.

“The issue in almost all of these serial-killer cases is the complete absence of a functioning superego which thus fails to act as a restraining mechanism,” says Dr. Stephen Reich, director of the Forensic Psychology Group in New York City. “It can be a homeless drifter or an M.D. In either case, there’s a sense of impotence involved and compensatory power and a feeling of insignificance which they overcome by taking on the role of the all-powerful giver of life and death.”

What may be most remarkable is how institutions dedicated to first doing no harm instead allowed such a creature to work, unmolested, on their behalf.

Leave a reply