Sanskrit is one of the oldest languages in the world, and is often considered to be one of the most refined. A Nagpur-based Sanskrit weekly has been keeping the language and its significance alive for over 65 years.

Sanskrit-Bhavitavyam was started in 1951 by Pradnyabharati Dr. Shridhar Bhaskar Warnekar, an erudite scholar, a musician par excellence, and an expert in the field of Yoga. It happens to be the only Sanskrit weekly in the world, boasting of a steady continuum in publication. “There has been no break,” the editorial board proclaims proudly. Bhavitavyam functions under the aegis of the Sanskrit Bhasha Pracharini Sabha.

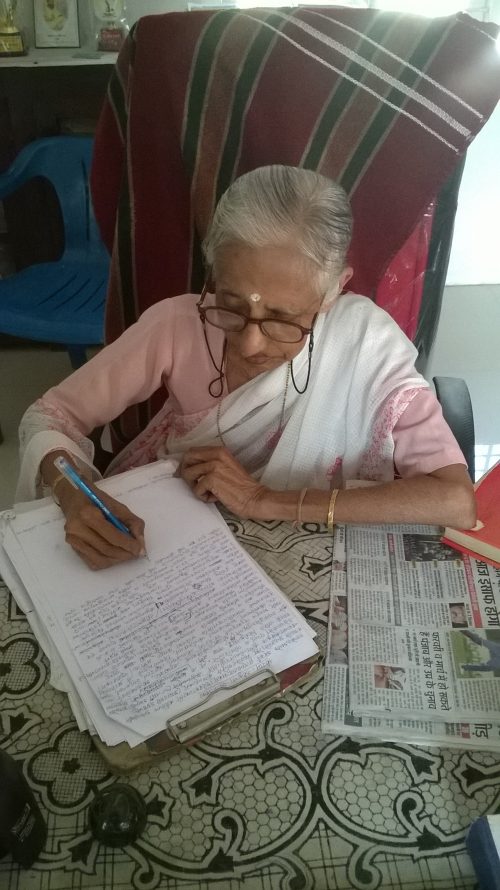

The Sanskrit Bhasha Pracharini Sabha is located in a quiet lane of the Civil Lines area of Nagpur City. Dr. Leena Rastogi, a reputed scholar of Sanskrit, is at work in her office. Warmly greeting me with “Katham Asti Bhavaan? (How are you?),” she arranges for a place for me to sit.

Although she is hesitant to speak about herself, she finally gives in after repeated requests. I am her student after all!

Dr. Rastogi has been the editor of the Sanskrit-Bhavitavyam, the mouth-piece of the Sabha, since 2005. She says, “Much of the work is now managed by Dr. Veena Ganu, Dr. Sharda Gagde, and Dr. Renuka Karandikar.” (All of them are Sanskrit scholars.)

Dr. Warnekar was in fact the first editor of the magazine, followed by Dr. Keshav Ramachandra Joshi and subsequently Dr. N. R. Varhadpande, all eminent Sanskrit scholars in their own rights. Accordingly, Dr. Rastogi is the fourth editor of the magazine. Born in Vadodara, she acquired her first degree from Wilson College, Mumbai, and went on to receive her doctorate from the University of Jabalpur. After teaching at a college in Umred, she recently settled in Nagpur.

Wholly and solely dedicated to Sanskrit even at the age of 77, Dr. Rastogi is also a renowned Ghazal Lekhika (Ghazal Writer).

She has as many as 13 books written in Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, and English to her credit.

One of her stories Katha Ek Kilakasya (Story of a Pin) has been included as part of the curriculum for the First Year undergraduate students of Amravati University. Her poem Namami Rashtradhwajam (Bowing before the National Flag) is a compulsory read for students of Standard X (Maharashtra Board); another story Kim Esha Me Putra? (Is he my son?) is part of the prose for the final year undergraduates of Nagpur University.

Currently, she is working on the life history of Shridhar Bhaskar Warnekar, a task given to her by the Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. She has also been asked by the Sundar Sanskar Va Swadhyaya Mandal, Pune to collect information on the lesser known Upanishads of the country.

“Enough about me,” she says, and the topic drifts to the life of Dr. Warnekar. Dr. Warnekar was born on 31st July, 1918 in Nagpur, in a Marathi family with meagre means of income. Since buying books was a costly affair, he would learn all his lessons by heart. This led to an interest in vocal singing, which he later developed into classical Sangeet to assist his poetic works like Tirtha-Bharatam. His most respected work on the history of the Maratha ruler Shivaji Maharaj (Shrishivarajodayam) won him the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1974. He was also conferred with the title of Pradnya Bharati by Jagadguru Shri Shankaracharya.

Dr. Warnekar was also the President of the Yogabhyasi Mandal, Nagpur, an institution that teaches yoga free-of-cost to all sections of society.

Dr. Rastogi says that due to her affinity for Sanskrit, Dr. Warnekar considered her as his own daughter. She then goes on to name some of his exceptional poetic creations: Vivekanandvijayam (The Victory of Swami Vivekananda), Ramkrishnaparamhamsiyam (dealing with the life of Ramkrishna Paramhamsa), and Vatsalyarasayanam (on Vatsalya Rasa, one of the rasas of Indian classical poetry, dance and drama), to name a few.

Our conversation then turns towards the role of the Sanskrit Bhasha Pracharini Sabha in keeping the rich culture of Sanskrit alive. I am told that a number of Vargas (classes) are conducted here free-of-cost, such as those on grammar, the Upanishads, and the Gita. An exam for students of Standards VI to XII is also conducted by the Sabha to demonstrate the importance of Sanskrit grammar. “Around 6,000 students sat for the exam in 2015,” says Dr. Rastogi.

Apart from this, the Sabha also undertakes the arduous task of getting books of Sanskrit scholars and enthusiasts published.

Dr. Chandragupta Warnekar, the eldest son of Dr. Shridhar Warnekar, runs a course on Sanganakiya Sanskrutam (studies dealing with coding a program in Sanskrit). Another noteworthy task taken up by the Sabha is Patheyam, a project to collaborate between science and Sanskrit. Scientists and Sanskrit scholars sit together to design experiments as documented in ancient texts. The group has so far conducted 23 experiments – and also presented the same – at a meet of the Indian Science Congress, where their effort was highly appreciated.

It is getting a bit dark outside and I have exhausted almost all of my questions now. I decide to leave, but only after having a look at the Sabha’s Vachnalaya (library) which has been meticulously maintained.

The library possesses many rare books of Sanskrit and allied topics besides the recent works of Sanskrit scholars.

The weather is pleasant and the road bears a deserted look. On the board at the gate, one reads the name of the weekly once again – Sanskrit-Bhavitavyam, meaning, “We ought to be cultured!”

Leave a reply