She was attacked at a rural police station, and her landmark case awakened India decades ago. But did she manage to love, have children, find happiness? New headlines about rape in my homeland set me on a journey to find her.

She was 14, maybe 16, when they raped her. It was 1972, and I was 9. The India of her youth was the India of mine — except she lived in utter poverty.

She was an orphaned adivasi, a tribal girl, and she performed the most menial of jobs to put bread in her belly. She collected cow dung with her bare hands, shaped it into patties, slapped them on walls to dry and then sold them as fuel. It’s a sight and smell familiar to me. I used to watch women in my Kolkata neighborhood do the same thing, using the back wall of my grandfather’s house. I couldn’t imagine plunging my hand into piles of animal waste.

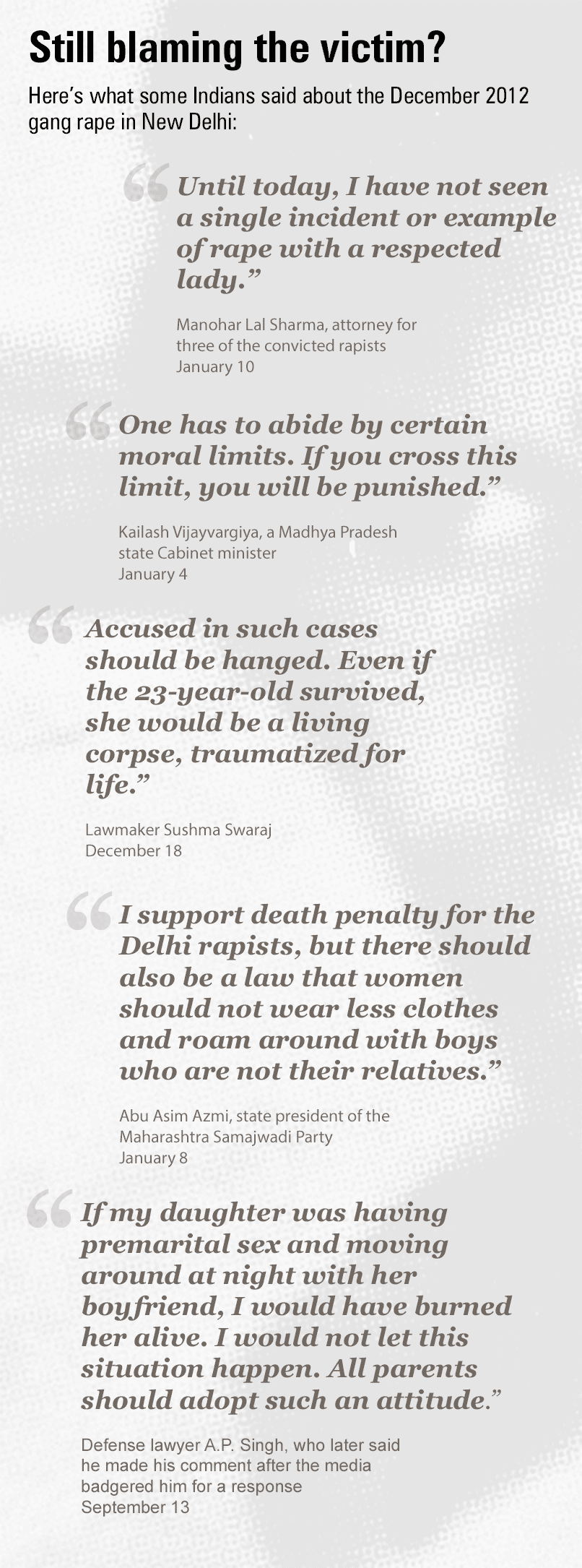

Women march in New Delhi in 1980 to demand that the Indian Supreme Court reconsider the case of Mathura, who accused two policemen of raping her when she was a teenager. The high court overturned the convictions of the two constables.

But rape knows no boundaries of class or culture.

After it happened, she might as well have worn a scarlet letter on her chest. Such was the stigma of rape in India then. She was brave to speak out and did what few women back then did. She took her case to court.

But the highest court of the land did not believe she was telling the truth. The justices overturned the convictions of her attackers, two police constables who maintained their innocence, and set them free.

Her case was monumental, both from a social and legal perspective. It sparked public protest for the first time about rape in India and led to the reform of sexual assault laws. It gave rise to a women’s movement in India, sprouting a host of groups dedicated to empowering women. At last, people here began to see gender-based violence for what it really is: a brutal act of power.

I first read about the case after I began working as a journalist in the United States and developed a curiosity about women’s rights around the world. Though the courts ultimately refused to believe Mathura was raped, history has come down on her side. She is uniformly depicted as a rape victim — not a woman who cried rape.

For me, her case became a prism through which I could see my homeland and measure its progress over the past four decades. Then, in December, another rape galvanized India. Thousands marched on the streets after a young New Delhi woman was viciously gang-raped on a bus, an act so horrific that she later died.

A headline in The Hindustan Times newspaper caught my eye. The accompanying column lamented that the attitudes of men had changed little since the landmark 1972 case. Some said the outcry in Delhi could be traced to the rape 41 years ago. Numerous other stories, opinion pieces and timelines on rape legislation mentioned the case.

But no one seemed to know what had happened to the victim, the teenage girl whose court-given name now popped up everywhere: Mathura.

Was she still alive?

So began my quest to find the woman who had innocently walked to a village police station to settle a domestic dispute and returned home a rape victim.

I wanted to find her for many reasons. In profound ways, I related to her.

Sweeping generalizations about my country in news coverage on sexual assault both embarrassed and angered me. I wanted to learn for myself how India, as a society, dealt with rape. And how Mathura had fared.

In some ways, life has not changed much for women in rural India since Mathura’s rape in 1972. At this chili processing plant in the town of Bhiwapur, workers make 80 cents a day de-stemming fiery hot peppers.

I knew how devastating rape could be, and I wondered how she had coped given her hardscrabble life, the crush of poverty, illiteracy and patriarchy. Did she manage to love, have children, find happiness? Had she heard about the New Delhi gang rape that pulled her name back into the news?

The answers to these questions would not come easily. Myriad phone calls — mainly to lawyers, journalists and activists — led nowhere. It was 40 years ago, they told me. She was a poor, uneducated girl who lived in a remote village.

“You will never find her.”

Seeing outrage for the first time

My journey begins outside a district court in south Delhi’s Saket neighborhood, where hundreds have gathered on a sweltering September afternoon for what feels like judgment day for all of India. The four men convicted in December’s gang rape are about to be sentenced.

From the main road outside the courthouse complex, I can see Select Citywalk, the luxe shopping mall where the 23-year-old woman had gone to see “Life of Pi” with a male companion. This six-acre retail heaven stands as an emblem of the new India, bursting with American and European commercial ventures such as Forever 21, the Body Shop and T.G.I. Fridays.

But social attitudes here lag far behind material gains. Men and women mingle but rarely touch — and never kiss in public. More than 80% will agree to marriages arranged by the parents, according to a poll this year.

On the night of December 16, 2012, the young woman and her friend boarded a private bus near this mall to make their way home to the suburb of Dwarka. The driver and five other men were drunk that night and looking for a joy ride. They dragged the woman to the back of the bus and beat up her friend; then they took turns raping her, using an iron rod to violate her as the bus circled the city for almost an hour. When they finished, they dumped their victims on the side of the road.

The woman’s internal injuries were so severe that almost all her intestines had to be removed. She developed sepsis and two weeks later, in a hospital in Singapore, she died.

The chilling nature of the crime haunted people. It was like a bomb exploded inside the collective Indian psyche.

A 10-year-old girl goes to school in Desaiganj, the town where Mathura was raped. Many people here still hold traditional views about the roles of girls and women in society.

There was raw anger over the failure of the nation to check this sort of extreme violence. Indian law prohibits the identification of rape victims, and two of the pseudonyms the media gave the Delhi woman spoke both of her impact on the country and her courage: Damini, which means lightning, and Nirbhaya, without fear.

Outside the court, I see those names swirling about me on crudely crafted cardboard posters. The crowd is clamoring for death sentences for the rapists. Inside, people crowd the balconies overlooking a courtyard, all the way to the seventh floor. They stand on chairs, stretch their necks to get a glimpse of Courtroom 304, where Judge Yogesh Khanna is about to proclaim his sentence.

Never before have I witnessed outrage in my homeland over the assault and killing of a woman.

Could this be the same place where I am afraid to get on a public bus or the metro at rush hour because inevitably I will feel a man’s hands on my breasts?

I used to complain to my mother about the stares I got on the streets. She told me not to wear sleeveless blouses or show my legs. India, she said, was conservative that way. But it was more than that. No matter what I wore, some men felt they could look at me with abandon — as if I were an object, as if they could overpower me at any moment and no one would care.

It was visual rape.

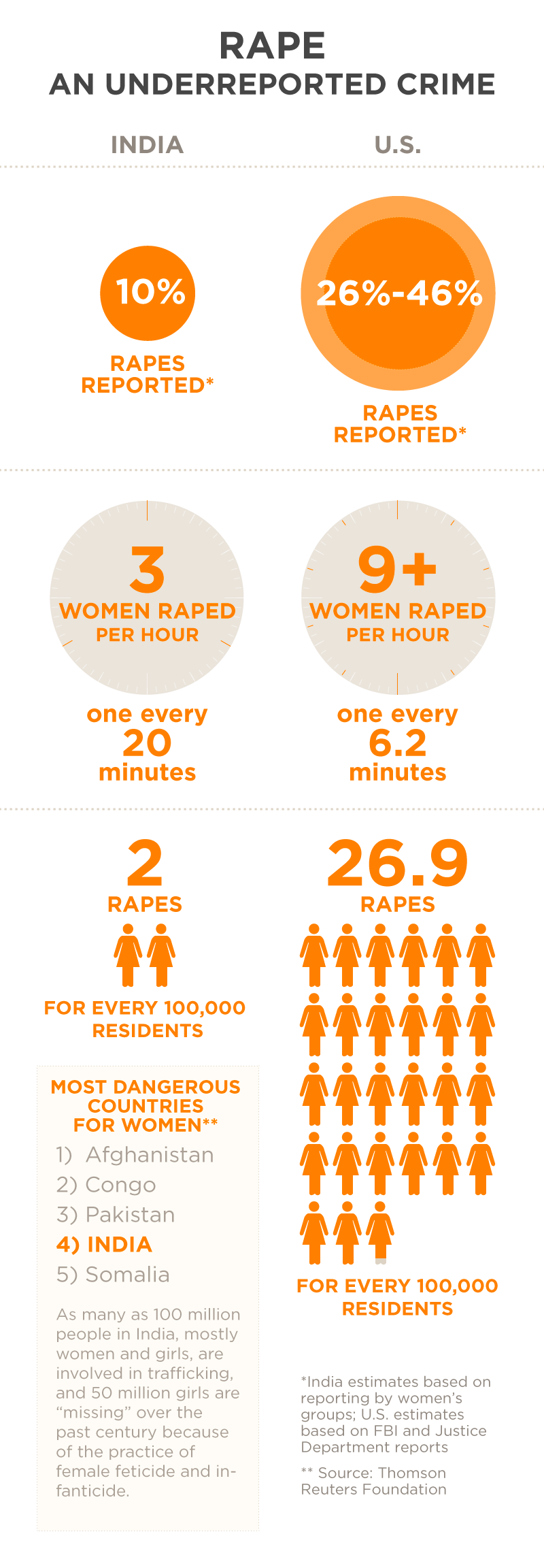

Here is the sad truth about India: A woman is raped every 20 minutes.

This case, Nirbhaya’s, was exceptional. Most of the time, violence against women — in the form of rape, bride burnings, wife battering — occurs out of the public eye and remains that way. Often the victim is too frightened to report the crime. She may fault herself for what happened or fear bringing shame to herself and her family. Or she lacks faith that the police — notorious in India for poor treatment of rape survivors — will investigate, or that the courts will prosecute.

Rape is an act forgotten with silence.

That is not the case here at the sentencing of Nirbhaya’s rapists. Just five minutes after court convenes, the decision is read aloud: the gallows for all four men. The people chant, “Fansi! Fansi!” Hang them! There’s something medieval about their demand for death. Nothing less will satisfy. Nothing less is justice for Nirbhaya.

In the midst of this madding crowd, I think of Mathura.

Her case also was exceptional: She was just a girl, a minor attacked by two policemen at a police station. I wonder what the reaction would be if those events occurred today?

Is this public condemnation I am witnessing truly a culmination of the women’s movement spawned by Mathura’s case, as one women’s rights activist suggested to me? An entire generation of urban, educated Indians has grown to adulthood in the years since.

But would there be similar indignation over a poor girl in a village? About 75% of India’s 1.2 billion people live in rural areas such as the one where Mathura lived, hundreds of miles south of Delhi in the central state of Maharashtra. Has the mindset of men — including those in positions of authority — changed in those places? Or are people still blaming victims for their rapes?

I am about to find out.

On the road to the scene of the crime

National Highway 9, known in these parts as Umred Road, snakes through verdant rice paddies and orange groves under unpolluted skies. This part of eastern Maharashtra is largely rural and so far unscathed by India’s monstrous rush to modernity.

National Highway 9 leads from the city of Nagpur to Desaiganj, a town in central India where many people are sympathetic to the anti-government rebels known as Naxals.

The unmarked road is no different than any other in India, laden with potholes as big as bomb craters. Cars screech to a halt for meandering water buffaloes and women balancing aluminum vessels filled with laundry on their heads. In their rainbow shades of saris they trek to the banks of the Wainganga River to wash clothes.

Here, centuries-old traditions still rule, especially among tribal people known as the Gond, their troubles in life masked by the serenity of the landscape. More than half survive on 50 cents a day, and they are often caught in the lethal crossfire between police and Maoist anti-government insurgents known as the Naxals, who have long had a stronghold in this area. As recently as July, six Naxals were killed after they allegedly attacked a police station.

Prabha Ram Take, a worker at the chili processing plant, is from the same generation as Mathura.

I’ve never before seen this part of my homeland. Most Indian city dwellers — and certainly tourists — don’t visit here. It’s rural and there are few attractions to draw them.

My reason is Mathura. My goal is to reach Desaiganj, the town where she lived when she was raped.

It’s in out-of-the-way places like this where violence against women still often goes unpunished or unnoticed — at least that’s what feminist activists have told me. It’s also a place that gives me discomfort as a woman and as an outsider who has come to ask difficult questions.

Traffic stops for an express train in Desaiganj, a town in Maharashtra state not often visited by India’s city dwellers or foreign tourists.

I’ve learned Mathura still has a few relatives and friends in Desaiganj, but there are no guarantees I will find her. I don’t know her real name, nor am I sure she is even alive. She would be 55 or 57 now. In rural India, chances of a long, healthy life are slim.

I also don’t assume she will want to talk about what she suffered four decades ago. Rape, I know all too well, is terrible to have to relive.

I gaze out the window, my thoughts whirring faster than the Toyota Innova’s engine. What exactly happened that night to Mathura? How is it that two policemen thought they could get away with using brute force on a girl still years from adulthood? Did they shatter her spirit?

The SUV makes its way past a soybean factory, through a village famous for paan or betel nut, an addictive chew for millions of Indians. An hour to the west is Tadoba, a Royal Bengal tiger reserve I’ve just read about in an Air India in-flight magazine.

We stop in Bhiwapur, where hundreds of men and women and even a few children work for a company that exports fiery chili peppers to Western nations. All day long, they de-stem dried red chilies, making mountains of crimson behind them and sending capsaicin molecules flying through the air. I begin coughing the moment I step out of the car.

A woman who introduces herself as Prabha Ram Take has been coughing for the 20 years she has worked here. She tells me she is 60 and makes 7 rupees for every kilo of peppers she de-stems. That’s about 80 cents a day. I stare at her sun-worn face and the rivulets of sweat settling into the crevices of her skin. I have never seen a picture of Mathura, but I imagine her to look a lot like Prabha Ram Take.

She asks me why I am here. I don’t know how to answer except to say I am looking for someone very much like her, someone who lives under similar conditions.

She lets out a hint of a smile. “Why are you looking for her?”

“Because,” I tell her, “something very bad happened to her many years ago.”

I realize I don’t know how to say rape in Hindi. India is a country of many tongues, and I grew up speaking Bengali, not the national language of Hindi. I understand it well enough to get by, and I know there is a word for rape. But I have never heard it used. The term I know is izzat lootna, or stealing a woman’s dignity. It is a euphemism, and like so many other words society substitutes for rape, it conceals the crime’s true horror.

‘They were human beings, too’

Before I speak to people who knew Mathura in Desaiganj, I decide to learn more about her assailants. I am eager to know if they still live in the area and how they shaped their lives after being accused of rape.

I head to the police station in Desaiganj, a town of about 25,000 also known as Wadsa. The station is housed at a paramilitary post; security presence is heavy here because of the Maoist rebels. One wall is plastered with photos of “wanted” Naxals.

The inspector, Annasaheb Manjare, has not yet arrived. I wait in his office and can see folders of documents piled on a metal shelf. Everything is still logged by hand, on paper. Maybe one of those files contains Mathura’s story.

When Manjare finally arrives, I ask for a copy of the police records of the case. There are none, he says.

We talk for a few minutes about the events of that night. I know the two attackers only by the names contained in court documents, Ganpat and Tukaram. I ask the inspector: “Do you know what happened to the accused policemen?”

His answer is “no.” It was 40 years ago, he says. What does all this have to do with him or any of his staff?

Then, he blurts out a telling thought about Mathura’s attackers.

“They were human beings, too. They were a part of society.”

The seeds of rape are many in India — among them, poverty, institutional gender bias and lack of education. But another force is the traditions and cultural norms that allow boys to grow up believing they are superior to girls. I think about the inspector’s subtle defense of the two policemen.

Did he mean they were acting as they’d been taught; that, in a way, it was only natural?

A childhood friend

In Desaiganj, I learn the names of Mathura’s relatives and friends, including a man named Motiram Meshram. He has known Mathura since her childhood.

Motiram Meshram has been a friend of Mathura’s since childhood. He testified against the two policemen she said raped her.

I meet him at his house in Shivaji Ward. It’s the same neighborhood where Mathura lived in 1972.

I mentally size Meshram up as a socially conservative man who probably did not make much of Mathura’s rape, maybe even blamed her in some way or justified it like the police inspector did. Instead I sit down with a man who surprises me.

At 65, Meshram has done better than many. He raised two sons and a daughter and makes a living farming rice. He owns a tractor and a two-room house that even has an air cooler inside, although it’s of no use on sultry days like this when the air is thick with dampness. Still, it’s a relief to talk out of the sun’s punishing glare.

I speak to him in Hindi. When I’m uncertain of his words, I ask a CNN producer, a native speaker, to translate.

Right away, I am struck by something he tells me. All this time, I’ve believed Mathura to be the victim’s court-given name. It isn’t. It is her real name. There was no attempt to shield her identity.

I strain to hear Meshram over the voices of first-graders at the Manavta Primary School next door. They are learning how to say numbers in English. “S-E-V-E-N!” they spell out in a lyrical chant. Behind the school are thatched-roof huts. This is where open drains exude the stench of human waste, where families survive every day on daal, or lentils, and flatbread known as rotis.

But many of the huts in the Shivaji Ward have been replaced by brick and mortar homes like Meshram’s. He takes me to see where Mathura lived. Her hut is long gone, and a new home is going up. People look at us suspiciously. Who are these people filming the construction? There is a high level of distrust of officials and law enforcement here. The crowd that has gathered thinks the members of the CNN crew are government surveyors, spying on the people. We are forced to leave when taunts and screams become outright threats.

Back at Meshram’s house, we sit on plastic chairs in his front yard. The three goats tied up to posts and the roaming roosters bristle at the afternoon interruption. I imagine life was not very different when Mathura lived here, except now everyone has mobile phones and television sets. But Meshram’s wife tells me that one, far more important thing has changed in Desaiganj.

Four decades ago, says Shantibai, men were good for nothing. They sat at home with their hooch, got drunk and then abused their girlfriends and wives, the sole wage earners in the family. She suspects Mathura may have suffered so.

“What was she like as a girl?” I ask Shantibai.

Women from Nawargaon, the village where Mathura now lives, wash clothes in an irrigation channel.

“She was pretty. Fair-skinned,” she says. “She was simple-natured.”

Her parents died when she was young and she, not surprisingly, learned to fend for herself. She lived with one of her two brothers, Gama, who herded cattle and did various other menial jobs. Mathura made money as a maid.

Sometimes, she found work with a woman named Nushi and spent time at her house. There, she met Nushi’s nephew. Ashok Kodape was tall and slender and an orphan like Mathura.

Ashok is no longer alive. But Meshram has asked Ashok’s cousin, Ganesh Kodape, to come over and speak with me. Ganesh is 54 now, has skin the color of coffee beans and large eyes that are fierce and gentle all at once. He dropped out of school after the second grade. He says everyone in his family — including Ashok — was poor, so poor that Ganesh didn’t wear any clothes as a boy.

He was only 13 or 14 when Mathura was attacked, and he doesn’t remember it well. But he tells me Ashok worked as a manual laborer.

Mathura and Ashok fell in love. They developed an intimate relationship and decided they would one day marry. Ganesh remembers Nushi treated Mathura as a daughter-in-law. In tribal communities, Mathura’s relationship with Ashok was not unheard of. But in the larger Indian society, she was a tainted woman for being single and sexually active.

Mathura’s brother did not approve.

Gama, according to court documents, lodged a complaint with the police that his sister had been abducted by Ashok and his family; that she was forced into prostitution. Either he didn’t believe Mathura was in love or he was embarrassed by the relationship and wanted to break it up.

Meshram continues his story. He remembers the night when police summoned Mathura to the station. She was required to make a statement regarding her brother’s complaint.

Then Meshram tells me something I didn’t know from reading accounts of the case. He tells me that he accompanied Mathura to the police station.

“You were there the night she was raped?” I ask.

“Yes,” he says. “I can take you there.”

An eyewitness account

Meshram and I stand before the old police station. It’s nothing more than a crumbling building. Moss and weeds devour the stairs to the second and third floors where there were once apartments. The concrete walls are bleak with mold and water stains. They look sad, like they have been crying for years.

There is only one burst of color here: the door and windows, painted a vivid United Nations blue. The building is padlocked, as if it holds something worth taking — secrets better kept hidden inside.

Meshram can’t remember the last time he was here. Maybe it was on that wretched day, March 26, 1972.

I ask him to take me back to that evening when police summoned Mathura. Ashok and Nushi planned to accompany her to the station. Ashok asked Meshram to join them on the mile walk from their homes.

Meshram pauses. I begin to think I will have to prod him for details, but then his narrative flows like a torrent.

He waited while the three made their statements to the head constable, Baburao. Ashok was asked to return later with some proof of age for Mathura. By then, it was almost 10:30 at night, and Baburao left because dinner was waiting for him at home. Mathura and her escorts also started to leave, but two constables, Ganpat and Tukaram, asked Mathura to wait inside the police station. Meshram waited for her outside, with Ashok and Nushi.

A shepherd makes his way to Mathura’s village with his animals.

Meshram points to the blue front door. It was 41 years ago, but he can clearly see Mathura even now, standing in the front room with the two policemen. It’s almost as though a movie of that night is playing in front of us.

She is wearing a cotton printed sari. And chappals, or sandals, on her feet. He can see Ganpat standing next to Mathura and placing a hand on her shoulder. And then, everything goes dark. The police officers switch off the lights.

“Ganpat, Tukaram!” Meshram shouts. “What are you doing in there?”

There is no answer. Meshram grows worried and bolts up the stairs to the second floor and asks the man who lives there for help.

“The girl,” he says, “is alone inside with the police. The lights are off.”

Meshram convinces the man and his friend to help them. They run back downstairs, enter the front room of the police station and plead for Mathura to make noise so they can find her.

But Mathura is silent.

That fact will later haunt her. Officials will view her silence as consent, though that night she told Meshram the police threatened to throw her, Ashok and his aunt behind bars without bail if she so much as made a whimper.

Then, she later said, Ganpat took her into a latrine behind the police station, loosened her underwear and — using a flashlight — stared at her private parts. He then dragged her to a veranda, shoved her to the ground, beat and raped her. After he was done, Tukaram took his turn. He fondled Mathura’s body but could not penetrate her because he was too intoxicated.

Motiram Meshram’s wife, Shantibai, says 40 years ago, men in Desaiganj were good for nothing. They drank hooch and abused their wives and girlfriends.

When it was over, Mathura came running out. Her hair was disheveled, her sari torn. Tears streamed down her face.

“What happened?” Meshram asked. “Did they misbehave?”

“They raped me,” she said.

Anger surged within Meshram. How could two men who were protectors of the law, supposed guardians of powerless people, do this?

“You are demons,” he told them. “You deserve to be punished, and we’ll ensure that. That’s our promise to you.”

I am taken aback by the tone of Meshram’s speech as he recounts history. I sense his anger even now.

Meshram and Nushi took Mathura to the local government dispensary. Dr. Sambhrao Khule said he was not authorized to conduct rape tests but gave them a reference letter for a larger hospital in Chandrapur, the city that was then the county seat.

Meshram remembers boarding a 10 a.m. bus the next day with Mathura. At the Chandrapur hospital, Dr. Kamal Shastrakar examined her.

“The girl had no injury on her person,” his report said, according to court documents. “Her hymen revealed old ruptures. The vagina admitted two fingers easily. There was no matting of the pubic hair.”

He found no traces of semen inside her but detected it on her clothes and underwear.

By then, almost 24 hours had passed since the attack.

Marked twice

Mathura withdrew. She cried a lot, Meshram remembers. She couldn’t concentrate.

“First, poverty made her vulnerable,” Meshram says. “Then this incident broke her from within. Completely. She lost everyone who was in her life.”

“Do dag,” Meshram says, raising two fingers. In Hindi, it means two marks.

Mathura was marked twice: She’d had premarital sex, and she had been raped.

What kind of future would she have?

Some people in Desaiganj grew suspicious of the police. But there wasn’t much outrage.

“We were poor and uneducated,” Meshram tells me. “How could we go up against the police? We were scared.

“Nobody gave importance to what was happening within the society. Nor would they stand up against injustice done to others. That’s why cases of rape were buried by people in those days. Rape, murder. … They went unreported.”

But Mathura wanted the perpetrators punished. She pressed charges, knowing how difficult it would be for her in court. It would be her word against that of two policemen.

The trial was held a few months later at the district court in Chandrapur. She and others who testified, including Meshram, were given 5 rupees (8 cents) a day to travel by bus from Desaiganj.

I was not able to find a transcript of the trial so I can’t be certain who testified on Mathura’s behalf besides Meshram. He says some of what Mathura told the court was used against her.

The defense lawyer asked why she didn’t scream. Did Ganpat or Tukaram cover her mouth with their hands? Did they gag her?

“No,” she replied.

In June 1974, the district court judge acquitted her assailants. He called her a “shocking liar” whose testimony was “riddled with falsehood and improbabilities.” She was used to having sex and must have consented to the police, the judge said. She claimed rape so that she would appear virtuous to her lover.

The case went to the Bombay High Court in Nagpur, a city about three hours’ drive from Desaiganj. On October 12, 1976, that court reversed the acquittals of the two police constables. Ganpat was sentenced to five years for rape; Tukaram got a year for the “assault or criminal force to a woman with intent to outrage her modesty.”

Whatever sense of justice Mathura felt was short-lived. In a 1978 appeal, the Indian Supreme Court overturned the convictions. It said Mathura must have consented because she didn’t scream, and there were no visible bruises on her body.

India’s rape laws at that time favored the accused. The courts did not presume a lack of consent in cases of custodial rape — when the victim is in the custody of authorities — as they do today. Instead the burden of proof fell on the victim, who had to convince the court she had not consented.

“No marks of injury were found on the person of the girl after the incident and their absence goes a long way to indicate that the alleged intercourse was a peaceful affair, and that the story of a stiff resistance having been put up by the girl is all false,” wrote Justice A.D. Koshal, who retired four years after the ruling and died in 2011.

I think about the restless crowds I’d seen at the courthouse in New Delhi. Would they stand up for Mathura as they had for Nirbhaya?

I pose this question to Meshram.

He tells me attitudes have changed a lot since the 1970s, not just among ordinary people but among people in power. “Had it happened today,” he says, “I am confident they would have at least gotten 10 years in jail.”

Again, I am surprised by Meshram’s words. Perhaps they are borne out of the hope that poor people in India can also get justice. Perhaps he feels that he, too, failed Mathura and cannot bear to believe that four decades later, it could happen again.

As I listen, I am struck by Meshram’s courage and compassion. I hope that he in no way blames himself. In helping Mathura, he went against the norms in those days. He is not the man I’d imagined. Quite the opposite. He’s somewhat of a hero in Mathura’s tale.

In my mind, Meshram stands as a symbol of the progress my homeland has made. Perhaps today, there are more men who think like him in places such as Desaiganj.

My journey is starting to answer some of the troubling questions I asked myself after the Delhi gang rape, after the media began reporting on sexual assault much more than before. The headlines gave the impression that the problem had suddenly worsened here when, really, India has been on an ebb-and-flow path of progress ever since the watershed moment sparked by Mathura. But I am not so sure attitudes have shifted as much as Meshram would like to believe.

I am reminded of a statement made by the lawyer who represented three of the men accused of raping Nirbhaya in Delhi. He suggested she would not have been raped if she were more virtuous. “Even an underworld don would not like to touch a girl without respect,” he said.

Is that not how Mathura’s judges saw her? They said she was “habituated to sex.” Therefore, she must not have been raped.

Meshram tells me that by the time of the Supreme Court ruling, Ashok had died from liver disease. Mathura tried to move back in with her brother. But Meshram says Gama shunned her.

Determined not to be abandoned, Mathura agreed to marry a man named Bhagwan Attaram and moved with him to another village. There she hoped to put the past behind her. It is the choice of many rape victims: to go silent.

Mathura wanted to start again among people who may not have heard her story. She had no idea of the national storm that was brewing. And that she was smack in the middle of it.

‘Millions of Mathuras’

In Delhi, Upendra Baxi read the Supreme Court’s 1978 decision with utter shock. The dean of the University of Delhi law school felt compelled to speak his mind on what he believed was a travesty of justice and, more importantly, a disgrace to human rights in India. But what could he do?

Women wait at a rural help center in Desaiganj. Mathura’s rape spawned a movement to fight violence against women in India.

He endured 10 sleepless nights before an idea sprouted: He would write an open letter to the chief justice. Rape was not a matter of national conscience in 1978. Baxi intended to make it one, for the sake of the “millions of Mathuras” who didn’t even get as far as filing the first police report.

He intended to change Indian rape laws so that the burden of proof would shift away from the victim. He intended to escalate punishment for rape, to make sure the real name of a rape victim never appeared in public, to get rid of absurd metrics such as the two-finger test performed on Mathura.

His letter to the chief justice would outline all the reasons why the decision was wrong:

“What matters is a search for liberation from the colonial and male-dominated notions of what may constitute the element of consent, and the burden of proof, for rape which affect many Mathuras on the Indian countryside.

“Nothing short of the protection of human rights and constitutionalism is at stake.”

The letter was co-signed on September 16, 1979, by three other prominent Indian lawyers.

In those days, the Supreme Court was inaccessible to most Indians. Ordinary citizens did not have the right to petition the court. Nor was it customary to pen public letters to one of the most powerful institutions in the land. No media outlet thought it newsworthy or appropriate to publish the letter.

It was only after The Dawn newspaper in Pakistan printed the letter a few months later that it appeared in the Indian media, Baxi told me. The Supreme Court did not respond, but the letter had the same kind of effect that news of the Delhi gang rape did last year, though on a smaller scale. Indians, mainly women, were shocked by the plight of Mathura.

On March 8, 1980, on International Women’s Day, thousands of women marched on the streets of Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Nagpur. They included Seema Sakhare, who went on to form one of the first organizations in India to take on the issue of violence against women.

Now 80, Sakhare told me she was so taken with Mathura’s case that she visited Desaiganj to see if she could help her. She even stood on a stage with Mathura at an early anti-rape rally. Then, like everyone else in India, Sakhare, too, lost touch with the woman who’d become a rallying cry for the country.

This is the legal and social history I know as I speak with the people of Desaiganj, many of them unaware of the importance of events that took place here in 1972. But Meshram knows. He knows that Mathura’s name became synonymous with the changes that Baxi proposed, and the reforms that followed.

A man in Mathura’s village carries branches and twigs on his head, a common way to transport goods by foot.

In 1983, a new category was added to criminal laws dealing with rape. When a victim is in the custody of the state, as was Mathura, the law mandates that a court presume a woman who says she did not consent is telling the truth. Mathura’s case also led to rape trials being conducted as closed proceedings and to a ban on identifying victims by their real names.

Had Mathura’s name not been everywhere, would she have stayed in Desaiganj? Perhaps. But as it were, she left. And only a few people from her previous life stayed in touch. One was Meshram. He has seen Mathura now and then over the years.

But he never spoke publicly again of what happened — until last December, when news of the Delhi gang rape reached Desaiganj.

“It happened here, too,” he told people in the Shivaji Ward neighborhood. “Forty years ago, it happened.”

No one listened. Some even thought he was getting senile, making things up.

“When is the last time you saw Mathura?” I ask him as the sun sets and darkness descends on the old police station.

He pauses to think. “It must have been four years ago. I went to Nawargaon (her village) and she saw me on the street. She was selling bamboo baskets. She recognized me and asked me to come over for a cup of tea. She seemed happy.”

Four years. I wonder what has become of her since? For the first time, I dare to hope that I will find her.

I ask Meshram to take me to Nawargaon. Maybe Mathura will be open to speaking with me if she sees a familiar face.

The end of my quest

We push westward for two hours. Any semblance of modern life vanishes as the car heads deeper into forested lands swarming with Naxals. The far-left Maoist movement finds a great deal of support here among tribal and indigenous people who feel displaced by encroaching corporations or mistreated by politicians and police.

Meshram has forgotten the exact location of Mathura’s house. We drive to the central market in the village and ask, mentioning her husband’s name.

A 1980 story I read in The Times of India said Mathura had married Attaram in 1975; that he only learned of his wife’s rape after the Supreme Court judgment. But Meshram tells me Attaram knew the sad facts of Mathura’s life before the wedding. “He is a good man.”

I feel my heart racing as we approach the three-room government-sanctioned house where Mathura lives. She steps out when she sees Meshram and invites us inside.

She is not too different than I imagined — small, maybe about 5 feet tall and light-skinned for an adivasi woman. Her hair is oiled back in a bun, and a maroon stick-on bindi adorns her forehead. She drapes her sari around her shoulder. It’s cotton and printed, like the one she was wearing the night she was raped.

I want to say so many things. That I am sorry for everything she’s endured. That I understand. But I tell myself to wait, to gauge her reaction.

Newly hatched chicks and a barking stray dog scurry out as we enter. It’s dark and hot inside. Electricity has not yet found its way to Mathura’s house.

The front room is filled by two wood and jute cots carefully balanced on the undulating dirt floor. The walls are empty except for four pictures, including a recent portrait of Mathura with her husband.

He is not here today. She says he is out collecting bamboo; the family makes a living selling baskets.

The pictures seize my attention momentarily. When all you have is so little, they seem to speak volumes. One is of Mahatma Gandhi. Another is of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Both led India to independence from British rule. The third is a small poster of Durga, the Hindu goddess of strength.

I stare at Durga, fierce with her 10 arms, each carrying a weapon that could instantly kill a man. How ironic, I think, that Indians choose to celebrate the force of good triumphing over evil in the form of a woman.

‘I had no choice’

I explain to Mathura who I am, why I am here, that I have been trying to find her for some time and journeyed almost 9,000 miles to see her.

Mathura tells me she has lived in this village ever since she married Attaram. She has two sons, she says. A third died when he was only 5 months old.

“Why have you come to see me?” she asks. “No one has come to see me in all these years. No one came to help me.”

I ask if she’s heard of Nirbhaya, the young woman who was gang-raped in Delhi.

Mathura nods her head. Yes.

“Do you know your name was in the newspapers after that gang rape?” I ask.

“No,” she says. “What did they say?”

I explain to her the significance of her case. I ask if she will speak about what happened.

She begins to answer. But then her oldest son, Papu Attaram, 25, comes between us. He looks nothing like Mathura. He is tall and dark and wears tight jeans and a polo shirt. In his left hand, he clutches a mobile phone. With his right hand, he gestures to me.

“We are not interested in anything you have to say,” he says, speaking for his mother.

The sons know their mother’s cruel history, but not everyone around them does. I wonder if they might have been more open to speaking to me had her identity not been revealed all those years ago.

“I tried very hard to forget,” Mathura tells me. “I tried very hard to start my life all over again. I had no choice.”

I want to tell her that I know what she means. Mathura was 14 when she was raped, maybe 16.

Activist Seema Sakhare went to visit Mathura after India’s Supreme Court overturned the convictions of the two policemen. Sakhare believes women who are raped in India are then raped again by the courts and society.

I was 18.

It happened on a college campus in the United States more than three decades ago and yet, sometimes, every detail of the violence feels fresh — his smell, his strength, his force and most of all, his eyes. This is one of those moments. I wonder if Mathura feels the same way about her attackers.

I want to tell her that this is another reason I wanted to find her. But I can’t break the silence I’ve kept for so long. The words won’t come out.

I look at her and think that in the most callous of ways, poverty and a lack of education helped save her. She was not like Nirbhaya in Delhi. Nirbhaya was a college student, studying physiotherapy. Had she survived, she might have had to deal with the stigma of rape in circles that mattered to her career and family. But Mathura did not have time to dwell on her trauma. It didn’t matter what people thought or said. She was forced to go back to the daily routine of her life in order to eat.

My thoughts are interrupted by her sons. “The government and police are useless,” Papu Attaram says. “I have a good mind to join the Naxals.”

Sakhare stands with Mathura, left, at an anti-rape rally after the Indian Supreme Court ruling. This photo appeared in a booklet about Sakhare’s career as a women’s activist.

His sentiments strike me as the norm in this part of India. I understand now that he equates me with the establishment, one that failed his mother 40 years ago. I also understand that he will not allow his mother to speak freely, that Mathura has no say in the matter. They have nothing but their reputations. They will not risk the black mark of rape again.

I don’t want to put the family in jeopardy. But I cannot help but feel disappointed. I had so many questions to ask her.

Attaram hands me a glass of sugary chai. At the same time, he suggests it’s time for me to leave. He expresses anger at Meshram for having brought me to see his mother. And he laces his words with threats. He tells us he has friends in this village. Naxal friends.

If her sons were not here, I think, Mathura might have burst open like a levee over a swollen river. But that will not happen today.

She tells me the only other outsider who ever came to visit her was Seema Sakhare, the feminist from Nagpur, who believes Indian women who are raped are then raped again by police, by courts and by society. That Mathura stands as proof.

I swallow the last few drops of tea and get up to leave. She agrees to a quick iPhone snap of the two of us if I promise not to publish it. Then she takes her place again behind her sons.

They come to the door as I step outside. “Are you happy, Mathura?” I ask.

“Happiness. Sadness. What does it matter?” she replies. I look down, unsure of how to respond.

She finishes her thought. “What’s important is that I’ve survived.”

Leave a reply