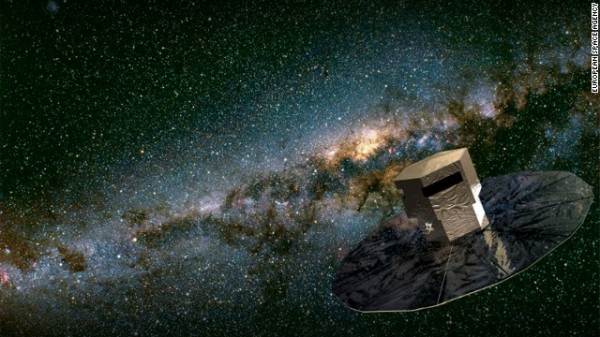

An artist's impression of the European Space Agency's space telescope Gaia in operation.

- European Space Agency’s Gaia has been tasked with making a 3D map of the Milky Way

- Telescope so sensitive that makers say it could measure a human thumbnail from Moon

- One of Gaia’s objectives is to help in hunt for exoplanets

- Mission applauded for building up most accurate charts of the cosmos

What do you need to map a billion stars? A billion-pixel camera certainly helps.

Scientists hope to glean more clues about the origin and evolution of the universe, and in particular our own galaxy, when a camera of this incredible scale — fitted to the Gaia space telescope — is launched Thursday.

Gaia, which is due to lift off from French Guyana, has been tasked with mapping the Milky Way in greater detail than ever before.

Designed and built by Astrium for the European Space Agency (ESA), the makers say the telescope is so sensitive that it could measure a person’s thumbnail from the Moon, or to put it another way, detect the width of a human hair from 1,000km (620 miles) away.

The mission’s aim is to build a three-dimensional picture of our galaxy, measuring precise distances to a billion stars. Even this is a small fraction of the Milky Way, as astronomers believe there are at least 100 billion stars in our galaxy.

Astrium says Gaia is also expected to log a million quasars beyond the Milky Way, and a quarter of a million objects in our own solar system, including comets and asteroids.

“It can do it with incredible accuracy. It’s the biggest camera ever put into space,” said Ralph Cordey, head of science and exploration at Astrium.

He said the spacecraft cost 400 million euros ($549 million) to build, but the total cost of the mission would come to 740 million euros ($1.02 billion) when the expense of the launch and running the mission for its projected five-year lifetime are included.

If successful, Gaia will add to the knowledge gained from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, which is still in operation, and ESA’s Hipparcos satellite, which gathered data until 1993.

The value of putting a billion-pixel camera into space has been championed by Robert Massey from the UK’s Royal Astronomical Society.

“Gaia is an amazingly ambitious mission,” he said.

“Until now astronomers have relied on very indirect methods to gauge the distance to all but the nearest stars, meaning that the foundation on which we build a map of the universe is surprisingly weak.

“Building on the work of the pioneering Hipparcos satellite that mapped the stellar neighbourhood in the 1990s, Gaia will be used to carry out work analogous to the cartographers who surveyed the Earth in the 19th and 20th centuries, building up the first accurate charts of the cosmos and helping us better understand the structure, history and fate of the galaxy we live in.”

One of Gaia’s objectives is to help in the hunt for exoplanets — new worlds beyond our own solar system.

NASA’s Kepler mission has so far confirmed the existence of 167 exoplanets with hundreds more being investigated, but Cordey anticipates Gaia will likely discover thousands of new planets, while further missions will be able to uncover more detail about them.

In a recent interview with CNN, George Whitesides, CEO of Virgin Galactic — the company planning to take tourists into space — said he thought that within a lifetime it would be possible to detect seasons on far-off worlds.

He may have not have too long to wait, as Astrium is already working on design concepts to examine exoplanet atmospheres — which may provide signs of seasonal variations.

“We are designing missions that could probably do that very thing — it’s not science fiction,” said Cordey.

Leave a reply