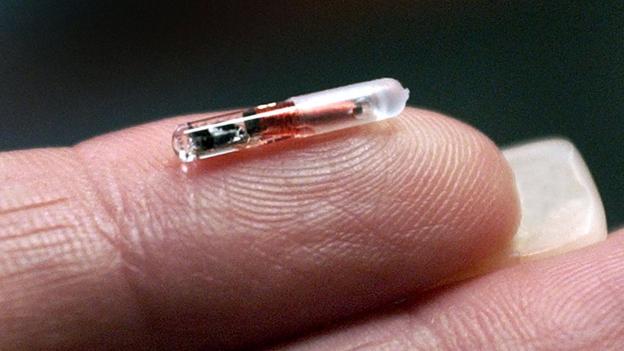

Medical history

This chip, manufactured in the early 2000s by a company called VeriChip, stores personal medical information

With a chip under your skin, you can do everything from unlocking doors to starting motorbikes, says Frank Swain, who has been trying to get his own implant.

A few years ago, I perched on the edge of my bed in a tiny flat, breathing in a cloud of acetone fumes, using a scalpel to pick at the corner of an electronic travel card. More than 10 million Londoners use these Oyster cards to ride the city’s public transport network. I had decided to dissect mine. After letting the card sit in pink nail polish remover for a week, the plastic had softened enough that I could peel apart the layers. Buried inside was a tiny microchip attached to a fine copper wire: the radio frequency identification (RFID) chip.

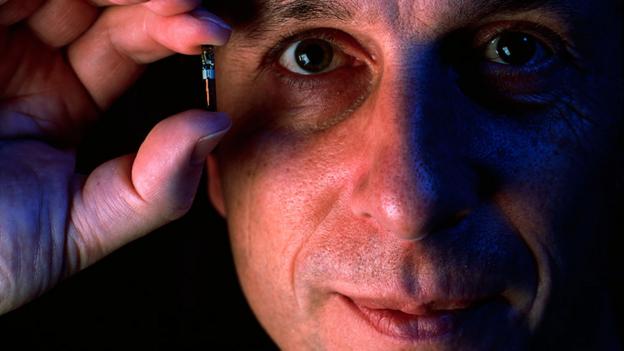

First cyborg

British researcher Kevin Warwick was one of the first people to have a chip implanted – in his forearm.

My goal was to bury the chip under my skin, so that the machine barriers at the entrance to the Underground would fly open with a wave of my hand, as if I was some kind of technological wizard. But although I had the chip and an ex-Royal Marines medic willing to do the surgery, I failed to get my hands on the high-grade silicone I’d need to coat the chip to prevent my body reacting against it. Since then, people have used the technique I helped popularise to put liberated Oyster chips in bracelets, rings, magic wands, even fruit, but the prize for first London transport cyborg is still up for grabs.

Multi-functional

Warwick’s sub-skin chip allowed him to be tracked and unlock doors; others have used their chips to start vehicles.

The person who does will find themselves inducted into the community of “grinders” – hobbyists who modify their own body with technological improvements. Just as you might find petrol heads poring over an engine, or hackers tinkering away at software code, grinders dream up ways to tweak their own bodies. One of the most popular upgrades is to implant a microchip under the skin, usually in the soft webbing between the thumb and forefinger.

Many people now have chips implanted in the fleshy part between thumb and index finger

Take Amal Graafstra, a self-described “adventure technologist” and founder of biohacking company Dangerous Things in Seattle, Washington. He is a double implantee – he has a microchip in each hand.

In his right hand is a re-writable chip, the same kind used in Oyster travel cards, which can be used to store small amounts of data. By pressing his hand to his phone, information can be downloaded from his body or uploaded into it. The left contains a simple identity number that can be scanned to unlock his front door, log into his computer or even start a motorbike.

Tasty chips

Some companies, such as Proteus Digital Health, are developing electronic sensors that can be swallowed.

This month at the Transhuman Visions conference in San Francisco, Graafstra set up an “implantation station” offering attendees the chance to be chipped at $50 a time. Using a large needle designed for microchipping pets, Graafstra injected a glass-coated RFID tag the size of a rice grain into each volunteer. By the end of the day Graafstra had created 15 new cyborgs.

For other people, though, the idea of implanting themselves with microchips may conjure up spectres of surveillance and totalitarian control. “Every Hollywood movie has told them that implants are for tracking people,” says Graafsta. “People don’t get that it’s the same exact technology as the card in your wallet. When someone uses a credit card, wireless or not, they are tracked because several other corporations know who they are, when they purchased, how much they spent, and where they spent it.”

Chip in pin

At a recent conference in San Francisco, people paid $50 to be chipped with a needle device like this one.

Yet if that’s true, what’s the point of implanting it? Graafstra and his fellow cyborgs could just as easily use a chip inside plastic wallet to store data, and a key to open his front door or start a motorbike. “Yes, basically you’ve taken an RFID access card normally stored in a pants pocket and moved it to a skin pocket,” admits Graafstra. Still, there are some advantages: one benefit is that you’ll never lose the chip, and it makes physical theft impossible – at least unless a thief is prepared for some gruesome surgery.

Graafsta also points out that embedding the chip under the skin reduces the distance that it can be read with a scanner, making it more secure. When it’s in your arm or hand, there’s less chance someone can surreptitiously scan your details, by sweeping a card reader nearby.

Sub-skin capsule with chip that can be read by scanners

Ultimately, implanted microchips offer a way to make your physical body machine-readable. Currently, there is no single standard of communicating with the machines that underpin society – from building access panels to ATMs – but an endless diversity of identification systems: magnetic strips, passwords, PIN numbers, security questions, and dongles. All of these are attempts to bridge the divide between your digital and physical identity, and if you forget or lose them, you are suddenly cut off from your bank account, your gym, your ride home, your proof of ID, and more. An implanted chip, by contrast, could act as our universal identity token for navigating the machine-regulated world.

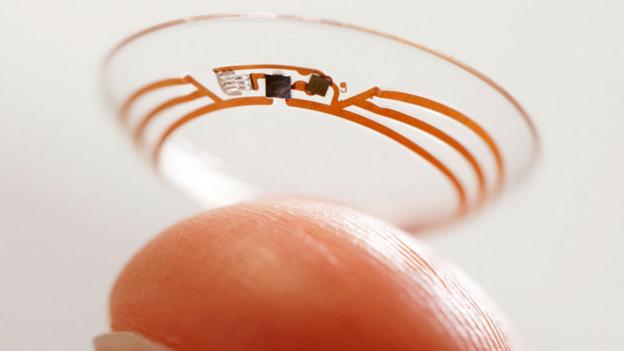

Smart eyes

Google is exploring the idea of electronics in the eye, held on a contact lens, to monitor health.

Yet to work, such a chip would need to be truly universal and account for potential obsolescence. My own flirtation with implanted technology came to an end when I moved away from London, making an Oyster-equipped hand pointless. Even with a return to London on the cards, I’m thinking twice about returning to my project, since Oyster cards are being phased out.

Cyber cat

Pets like this cat are routinely chipped to help locate them if they become lost.

Thinking ink

An alternative to implanted chips is the “electronic tattoo”, an adhesive worn on the skin.

Such a development may actually be a cause for optimism for implant enthusiasts, however, because instead of Oyster cards, London’s transport authority is allowing people to ride the subways and buses using bank cards. It marks the beginnings of a slow move toward a world where everything will be accessed from a single RFID microchip. If that day comes, I can’t think of a safer place to keep it than inside my own body.

Leave a reply