No expense will have been spared preparing Australia’s and England’s cricketers for the first Ashes Test on Wednesday – from training and physiotherapy, to a good dinner and a luxurious bed. It was very different for the first Australian team to visit the UK.

As Michael Clarke and his Australian side finalise their preparations for the Ashes, Cricket Australia will leave no stone unturned in its quest to regain the urn.

The Australian side arrived in the UK some seven weeks before the start of the first Test at Trent Bridge. Throughout its stay, the squad will adhere to a finely tuned schedule ensuring players start each match at the peak of fitness – and recover quickly afterwards.

But for the first Australian side to tour the UK, conditions were markedly different.

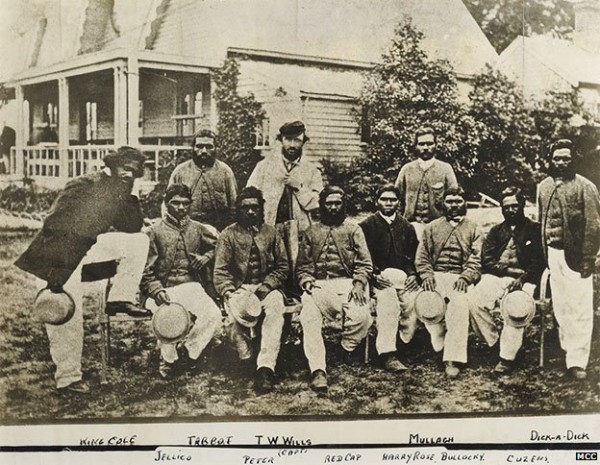

In 1868, English ex-pat and former first class cricketer Charles Lawrence brought a team of 13 Victoria-based Aboriginal players to the UK, intent on capitalising on public curiosity regarding “exotic races” following the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859.

Zellanach (Johnny Cuzens); A fearsome fast bowler

The tour faced strong opposition from the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines in Victoria, which feared that the Aboriginal players would struggle to survive the dismal English weather – it turned out to be a good summer, though the tour continued until October.

Concern had been heightened by the deaths of four players during and immediately after an abortive Sydney tour the previous year, at least two of them from pneumonia. Lawrence was therefore forced to smuggle the players from Victoria into Sydney, where they boarded a wool-carrying clipper bound for the UK on 8 February 1868.

Despite this, former Australian test cricketer Ashley Mallett, author of a book about the tour, Lords’ Dreaming, doesn’t believe the players were coerced.

“The players would have been happy for all the attention. In Australia at that time, Aboriginal people were treated very badly. Racism was rife,” he says.

The team eventually arrived at Gravesend on 13 May, after more than three months at sea – the outward journey alone took longer than the entire 2013 Ashes tour.

After a demonstration of their skills at Town Malling, the following day the Sporting Life wrote that they “gave great satisfaction to a critical coterie of spectators”.

“They are the first Australian natives who have visited this country on such a novel expedition, but it must not be inferred they that they are savages,” the report continued.

The first match featuring an Australian team in the UK began on 25 May 1868, against a Surrey side at the Oval. A crowd of 7,000 turned up for the first day’s play.

The Aboriginal side lost – as they did their first five matches of the tour – but several players impressed observers with the standard of their play. Johnny Mullagh was an all-rounder of genuine talent, while Johnny Cuzens was a fearsome fast bowler.

Squad members of lesser cricketing aptitude were given the opportunity to shine in other ways. Most matches featured two days of cricket followed by a third day of “sports”. This involved a mixture of the bizarre – running the 100 yards backwards and a contest involving picking up stones placed a yard apart – and more traditional Aboriginal events such as boomerang throwing.

Dick-a-Dick (the players were known by sobriquets as the public found their real names too difficult to pronounce), for example, had little in the way of cricket ability, yet became an undoubted star of the tour because of his skill at “dodging”. Spectators threw cricket balls from 10 paces, which Dick-a-Dick “dodged” using a parrying shield and leangle (an Aboriginal war club). He was hit just once on the entire tour.

One frightening stunt involved a group of players throwing spears at their team-mates – when they had finished, the men were encircled by a ring of spears, the sharp points buried in the ground.

The tour faced resistance from the more conservative members of the British cricketing fraternity, however. Lawrence was desperate for the side to play a match at Lord’s, knowing acceptance by the MCC would lead to a rush of lucrative offers from other clubs.

The Minutes of the MCC from 1868 show the Committee was dead against the idea of “tribal demonstrations” following any potential match, stating that “the exhibition was not one suited for Lord’s ground”.

The match was eventually agreed to and played on 11-12 June, against a side featuring an Earl and a Viscount. The Aboriginal side lost narrowly, but impressed with both their play and their dignified conduct. Despite the MCC’s misgivings, an afternoon of “sports” took place when the second day’s cricket finished early.

There followed a heated debate within the MCC Committee, though the Treasurer concluded by noting that “the performance seemed to give general satisfaction and the public would have been much disappointed if the sports had not taken place”.

As Lawrence predicted, the success of the Lord’s match led to further offers, but little consideration was given to the risk of exhausting the players. Matches were arranged in quick succession at opposite ends of the country, leading to a lot of travelling. The team was on the field for 99 out of a possible 126 days.

The tour was struck by one serious tragedy. King Cole, arguably the side’s most proficient fielder, had been taken ill with a chest complaint after the Lord’s match. His condition quickly worsened, and he died on 24 June 1868 – apparently of tuberculosis and pneumonia.

According to Aboriginal belief, it is a terrible thing to die away from home, and Mallett suspects that Lawrence may not have told the side of King Cole’s death for some time.

“In the Aboriginal culture, friends and relatives of a deceased person can sometimes mourn in ‘sorry’ mode for days, often weeks, and such a time span would have brought the tour to an abrupt halt,” he explains.

Two other members of the team, Jim Crow and Sundown, suffered bitterly after King Cole’s death, and returned to Sydney in September, a month before the tour ended.

In total the side won a creditable 14 matches, losing the same number and drawing on 19 occasions.

The tour was a financial success, officially netting a total profit of £2,176, but there is no evidence, Mallett says, that any Aboriginal player received payment.

Any possibility of subsequent tours ended with the implementation of the 1869 Aboriginal Protection Act, which gave the Victoria Aboriginal Protection Board the power to separate Aboriginal children from their families so that they could be “educated” within a European system. The new law meant overseas travel was now out of the question.

It was not until 1988 that the next Aboriginal side visited the UK, as part of Australia’s bicentennial celebrations, and it was a full 128 years after the 1868 tour before Australia fielded its first acknowledged Aboriginal test representative, Jason Gillespie, in 1996. The 1868 tour clearly provided little lasting legacy for Aboriginal cricket.

For all the difficulties they faced and the fact that one of the team died, Mallett believes the Aboriginal players genuinely enjoyed the tour, partly because they were treated with more respect than they were accustomed to at home.

It would certainly have been different from their work as agricultural labourers in Australia.

“If we are looking for an analogy it would have been akin to us being gathered up and flown in a space ship to the moon.”

Jason Gillespie

- Jason Gillespie (pictured) remains only modern-day Aboriginal cricket star

- Fast-medium bowler “Dizzy” Gillespie took 259 wickets in 71 Tests and scored double century against Bangladesh in 2006

- Retired from first-class game in 2008, he is currently first-team coach at Yorkshire CC

Leave a reply