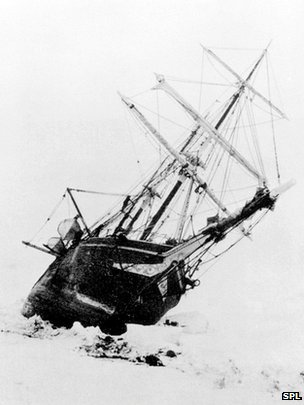

Ernest Shackleton’s famous ship, the Endurance, which he had to abandon in 1915 on his ill-fated Antarctic expedition, is probably still in very good condition on the ocean floor.

This is one conclusion from research that studied how sunken wood degrades in southern polar waters.

Experiments that submerged planks for over a year found they returned to the surface in near-pristine condition.

Scientists point to the absence in the region of wood-boring “ship worms”.

Anywhere else in the world, these molluscs would normally devour sunken wood rapidly.

But Adrian Glover from London’s Natural History Museum says the currents that circle the Antarctic likely prevent the organisms from getting anywhere near the continent.

It means the remains of old wooden shipwrecks, such as the oak- and pine-constructed Endurance, which was pierced by ice, may be remarkably well preserved in their water graves at the bottom of the sea.

The experimental planks were untouched

Shackleton's ship Endurance was holed by the pressing ice in Antarctica's Weddell Sea

“I think it’s a reasonable hypothesis to suggest Endurance is still in good condition, certainly based on our experiments and what we know about low microbial rates of degradation in the cold Antarctic deep sea,” Dr Glover told BBC News.

“Marine archaeologists and historians have long dreamt of finding the wreck and recovering artefacts from Shackleton’s expedition. But I’m interested in how deep-sea ecosystems function and how they recycle large organic inputs. All that oak and pinewood down there would be an amazing experiment in itself, and it would be fascinating to see it.”

The scientists recount how they put samples of whale bone and wood on platforms and then lowered them to the sea bed.

The recovery of bone and wood samples

They wanted to study the activity of some of the strangest creatures in the deep ocean.

These are the Osedax, or “zombie”, worms that consume the skeletons of dead cetaceans, and their wood-eating Xylophaga bivalve mollusc cousins.

The team had a simple idea to test: that Osedax should be abundant in a region that has relatively large populations of whales, but that Xylophaga ship worms ought to be extremely rare. The latter’s scarcity should be expected given that no significant tree growth has occurred in the Antarctic for millions of years, which means the amount of wood going into the Southern Ocean is minimal and therefore insufficient to sustain mollusc populations.

And this is indeed what the team found.

This whale bone was covered in a new species of zombie worm - Osedax antarcticus

After 14 months under water, the bones on the platforms were covered in zombie worms, including two previously undescribed species, but the wood was untouched.

The results support the contention that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), which sweeps around the White Continent, acts as a barrier to Xylophaga, preventing their larvae from entering the region from other ocean basins.

The study has also provided new insights into the evolutionary history of Osedax by comparing all the whale-bone-eating species now known to science with other, similar taxonomic groups.

It points to the zombie worms being most closely related to a clade of tiny mud-dwelling creatures that use specialist bacteria to consume chemicals in oxygen-poor sediments.

“Previous research had suggested that Osedax had diverged from groups that inhabited sulphidic hydrothermal vents and cold hydrocarbon seeps,” explained Dr Glover. “But as we added in more taxa and more genetic evidence, it implied they are more closely related to these mud-dwelling ‘beard’ worms. And that makes sense that the ancestor should be a sediment-dweller given what we think about the distribution of whale bones on the sea floor.”

Prof Lloyd Peck from the British Antarctic Survey was not involved in the study.

He said the cold Southern Ocean around the continent presented too great a challenge for a wide variety of organisms that could be found elsewhere in the world.

It might be that the way Xylophaga species digested wood simply did not function sufficiently well for the molluscs to establish themselves in the region – even if their larvae could cross the ACC and find rare sources of wood to colonise.

“It takes animals in the Antarctic marine environment a very, very long time to process a meal,” he told BBC News.

“These wood-boring molluscs use enzymes that break down the wood externally and then they digest it. It could just be that things operate so slowly that this way of life doesn’t work.”

Shackleton’s Endurance is thought to have settled about 3km (10,000ft) below the Weddell Sea surface. A number of groups have talked about trying to locate it.

David Mearns, from the UK-based company Blue Water Recoveries, is putting together one such plan. He said the new research reinforced his view that the wreck was in a good state.

“She was badly holed in the stern by large chunks of ice that broke through the ship’s sides below the water line and caused her to flood,” he explained.

“As the damage was too bad to be repairable, Sir Ernest was left with no other option than to abandon ship and set up camps on the ice. While Endurance will be a wreck, I expect to find her hull largely intact. She would have suffered additional impact damage when hitting the seabed, but I don’t expect this to be too bad.”

Ernest Shackleton and the Endurance

- 1914 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition hoped to become the first to cross Antarctica

- Crew faced hunger and loneliness when the Endurance became trapped by pack ice

- Endurance was eventually holed, sinking to the Weddell Sea floor in late 1915

- Crew lived on a drifting ice floe until its split forced them to take to lifeboats

- On reaching Elephant Island, Shackleton took a small group to South Georgia to seek help

- Rest of the crew were finally picked up from Elephant Island in August 1916

Leave a reply