The Yakuza are Japan’s long-standing criminal network. They’ve been in existence for 400 years and have instilled fear and respect among the population.

But are they more than a bunch of ruthless criminals? The truth has a habit of being more complex than first thought. They’ve blighted the country’s history, according to some. Others believe they are a foundation stone of modern society, for better or worse.

The organization started in the early 17th century, apparently born from necessity. Yakuza have their origins in the Burakumin. These lower classes had it tough in the hierarchy of Japanese culture. In a place where even a name was a luxury, they were shunned and made to live in isolation.

The most famous leader of the BLL, Jiichirō Matsumoto (1887–1966), who was born a burakumin in Fukuoka. He was a statesman and called “the father of buraku liberation.”

Why? The website All That’s Interesting writes, “The Burakumin were the executioners, the butchers, the undertakers, and the leather workers. They were those who worked with death – men who, in Buddhist and Shinto society, were considered unclean.”

So in order to survive, certain outcasts banded together and the Yakuza took shape. In addition to financial gain, they offered belonging, a sense of family. Mail Online explains that “Gangs are headed by an ‘oyabun’ or ‘kumicho’, which translates as ‘foster parent’ and ‘family head’, who give orders to their fiercely loyal ‘kobun’ — or ‘foster children’.”

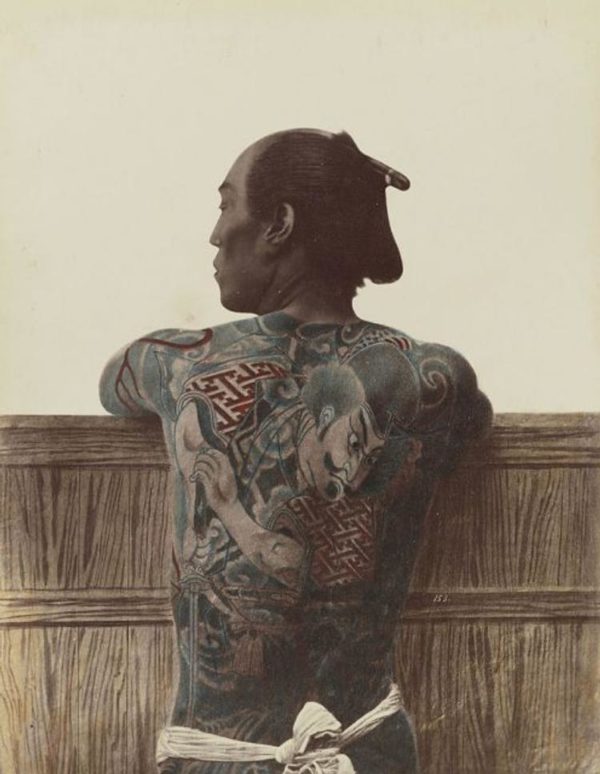

Being welcomed into the fearsome clan requires adjustment, not least having elaborate tattoos, or “ irezumi,” applied to the whole body.

A tattooed man’s back, c. 1875.

Another noticeable feature about members is that fingers from the left hand may be missing. A Yakuza who shames his boss has to sever the tip of a digit. This symbolic punishment affects the man’s ability to hold a sword, or a gun.

And it isn’t an entirely male domain. The Mail refers to “the few women in their ranks” who “are known as ‘ane-san’ – or ‘older sister’.”

Joining the Yakuza is not a licence to break the law. The groups operate under an honor code known as “ninkyo,” which respects their humble origins and provides help to those in need. For example, Yakuza arrived to help in the aftermath of the 2011 Tōhoku region earthquake and tsunami. Their response was reportedly faster than the government’s.

An early example of Irezumi tattoos, 1870s.

The idea of Yakuza reaching out to the disadvantaged has been around for centuries. As an article from the Los Angeles Times in 1996 states, there is a “romantic image of yakuza as wandering gamblers who helped the weak and punished the strong. After World War II, a popular genre of yakuza films perpetuated the Robin Hood theme.”

The same article estimates the number of Yakuza at 80,000. Over 20 years on, the figure is said to stand at 100,000. However, by some accounts Yakuza membership has declined in recent years, owing to economic and other factors.

It’s believed this is connected to the gangs’ increased sense of legitimacy, leading to government crackdowns. Yakuza staples of extortion, drugs, prostitution and the like became mixed up with the high fliers of the property market. The closer they got to white collar crime, the more of a priority they seemed to be for the authorities.

Leave a reply