The police were banging on the doors and the windows of her home while she cowered in the closet, a 17-year-old girl recounted. She remembered clutching her phone, crying, calling her mother.

“I was scared,” she wrote of the experience.

It may sound like a drug raid, or the climax of a movie. But in fact, the police, along with representatives of Connecticut’s Department of Children and Families, had come to take the girl for chemotherapy.

The girl, identified in court papers as Cassandra C., learned that she had Hodgkin’s lymphoma in September. Ever since, she and her mother have been entangled in a legal battle with the state of Connecticut over whether Cassandra, who is still a minor, can refuse the chemotherapy that doctors say is likely to save her life. Without it, the girl’s doctors say, she will die.

“It’s poison,” Cassandra’s mother, Jackie Fortin, said of chemotherapy in an interview on Friday. “Does it kill the cancer? I guess they say it does kill the cancer. But it also kills everything else in your body.”

Ms. Fortin continued, “It’s her body, and she should not be forced to do anything with her body.”

Doctors said in court documents that they had explained to Cassandra that while chemotherapy had side effects, serious risks were minimal.

On Thursday, Connecticut’s Supreme Court ruled that Cassandra had had the chance to show at trial that she was a “mature minor,” competent to make her own medical decisions, but had failed to do so. And so the chemotherapy treatments, which had already begun, will continue.

Cassandra was a healthy, artistic 16-year-old before the illness was diagnosed, her mother said. She liked to paint and draw, mostly abstract pieces, but also cartoons and silly things. She had a paper route and a retail job. She had a tattoo on her back of the character Simba from “The Lion King,” the namesake of her cherished, yellow tabby cat. She had been home-schooled since the 10th grade.

Then she found a lump on the right side of her neck. She went to her pediatrician, and after rounds of tests that dragged on for months, doctors at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center in Hartford told her she had Hodgkin’s lymphoma. According to court documents, her doctors said that with chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation, patients had an 85 percent chance of being disease-free after five years.

Ms. Fortin, of Windsor Locks, near Hartford, said that she and her daughter had wanted a second opinion and a fresh battery of tests. They had begun looking for a new team of doctors to verify the diagnosis, and hoped to find alternatives to chemotherapy.

But the state said in court documents that Ms. Fortin had not brought her daughter to some medical appointments and was “not attending to Cassandra’s medical needs in a timely basis.”

The Department of Children and Families took temporary custody of the girl in late October 2014. Two weeks later, she was allowed to go home, so long as she underwent chemotherapy. But after two days of treatment, she ran away from home.

“Although I didn’t have any intention of proceeding with the chemotherapy once I returned home, I endured two days of it,” Cassandra wrote in an essay published in The Hartford Courant this week. “Two days was enough; mentally and emotionally, I could not go through with chemotherapy.”

About a week after running away, Cassandra came home. In her essay, she wrote that she had returned because she was afraid her disappearance might land her mother in jail. In December, she was hospitalized.

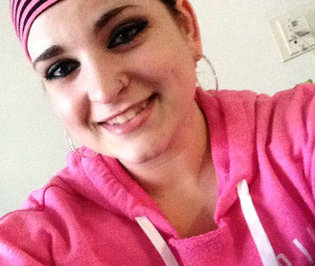

“I was strapped to a bed by my wrists and ankles and sedated,” she wrote in the essay, which was accompanied by a photo of her in the hospital. “I woke up in the recovery room with a port surgically placed in my chest. I was outraged and felt completely violated.”

“How long is a person actually supposed to live, and why?” she wrote. “I care about the quality of my life, not just the quantity.”

In a statement this week, the Department of Children and Families said it preferred to work with families, not compel them, but had no choice in some cases.

“When experts — such as the several physicians involved in this case — tell us with certainty that a child will die as a result of leaving a decision up to a parent,” the statement said, “then the Department has a responsibility to take action.”

Cassandra’s legal battle is not unprecedented, but it is unusual, said Dr. Paul.Appelbaum, director of the Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons.

“Nobody likes to overrule a parent and a child, particularly when they are in agreement,” he said.

Courts tend to be cautious about ordering treatment over a patient’s objections, Dr. Appelbaum said, and whether they do so often involves several factors, including the seriousness of the condition, the child’s maturity, and concern about whether the child’s opinions are being influenced by a parent or other third party. Several of those variables appear to have figured in this case, he said.

But Ms. Fortin’s lawyer, James P. Sexton, said that Cassandra was only months shy of her 18th birthday, when the decision about her care would be hers to make. By then, the chemotherapy will most likely be over.

Today she is confined to the hospital. Her communications are limited, as are her visits with her mother. Mr. Sexton said the family would continue to fight in court.

Leave a reply