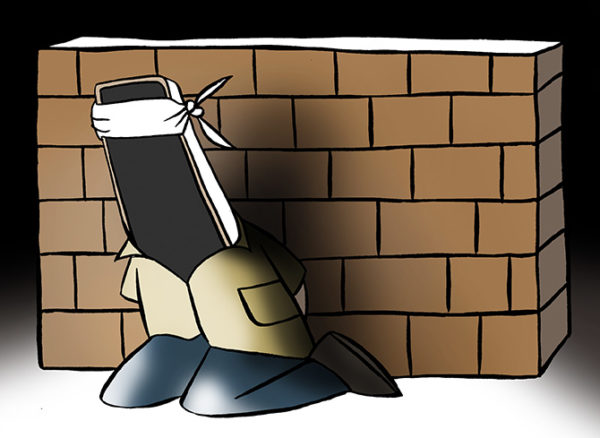

Journalism is a hazardous profession.

CBS News correspondent Lara Logan suffered a brutal sexual assault in Egypt’s Tahrir Square in 2011 while covering the country’s Arab Spring upheaval.

In 2014, an Islamic State video showed the beheading of Steven Sotloff, a US journalist who was held hostage by the militants.

Daniel Pearl, a Wall Street Journal reporter, was kidnapped and murdered in Pakistan in 2002.

Journalists all over the world have been disappearing and some have never been heard again.

Others have been imprisoned, tortured, and killed.

Nonetheless, journalists have never stopped reporting the truth as they see it, regardless of the consequences.

Today, however, the profession faces a graver danger, an existential threat: State-sponsored Internet-fuelled disinformation discreetly spread by countries such as Putin’s Russia; non-State actors such as Wiki-Leaks; and fake news Web sites that use Facebook, Twitter, Buzz Feed, and other social media that undermine the legitimacy, authenticity and trustworthiness of long-established news organisations.

Most bizarre, we have a gentleman in the White House who won the most powerful office in the world partly on the power of Twitter, thus, not only bypassing the traditional media gatekeepers but also making them look irrelevant and reckless.

President Donald Trump uses the bully pulpit to bully the press.

Since democracy cannot survive without a free, fearless, and robust press, what can news media organisations do to re-establish their reputation for authenticity, objectivity, impartiality, and trustworthiness especially after the US presidential election train wreck when all their projections and predictions went wrong?

Print newspapers organise themselves through sectionals, prioritising news as well as separating news from opinion pages. Today, however, most people get their news from smartphones.

But the smartphone has eliminated the space between news, opinions, and ads and sponsored news. In Google News, BuzzFeed and The New York Times are the same.

The brand does not matter for the hurried consumer of news.

Internet journalism is having a transformative impact on the news media ecosystem and the way people seek information and communicate with each other.

Many scholarly studies have discussed the decline of the traditional news media due to the rise of mobile news platforms.

Some newspapers have closed down, while others have become twice weekly or weekend newspapers.

Some newspapers such as US News and World Report have become completely online newspapers and lost their distinct identity.

The power of the smartphone and the reach and influence of the new generation of cyber-age grassroots civic journalists have grabbed the attention of governments around the world, particularly authoritarian and repressive ones, which have unleashed their brutal countermeasures.

The Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 259 journalists worldwide were jailed in 2016.

Forty-eight journalists were killed.

Traditional journalists have played important watchdog investigative roles based on their abilities to cultivate confidential sources.

For example, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of The Washington Post depended on a confidential source, Deep Throat, an FBI agent Mark Felt, for their path-breaking investigative reporting about Watergate that brought President Nixon down.

Corporate whistle-blowers have disclosed corrupt accounting practices, faulty products, and other malfeasances to traditional journalists so that society might benefit, as it has happened recently in the case of the Volkswagen emission scandal, for example.

But cyber journalism is changing the climate of news gathering and investigative reporting. Today online journalists, who may originate their investigative reporting from anywhere, can provide readers with unfiltered news, just as BuzzFeed did by publishing raw unverified blackmailing dossier about Donald Trump’s liaison in a Moscow hotel long before he entered the presidential election race.

Some non-profit organisations publish news leaks and classified information from clandestine anonymous sources.

Some are challenging the traditional news media to launch their own investigation for their commercial customers.

Sometime they collaborate, as it happened in 2010 between WikiLeaks and some major newspapers including The New York Times, The Guardian (London) and Der Spiegel (Germany), regarding the release of classified documents about the Iraq War.

Now we have a new media actor on the world stage, Putin’s Russia, and perhaps others, who can do a better job than Deep Throat did for The Washington Post investigative reporters.

The spread of selective disinformation by Russia, according to US intelligence agencies, about Hillary Clinton might have played an unspecified role during the presidential election.

It’s not only online journalists and whistle blowing social media sites but also private spy agencies that have begun to investigate hidden public spaces where earlier traditional journalists used to go.

Non-media foreign agencies that have played a role in US politics may also do so in other democratic countries such as India by spreading disinformation.

In this age of democratisation of news, alternative truths, alternative realities and Russian kompromat, the solution is candid, straightforward journalism.

Although it may be impolitic to call the US President a liar, journalists must call a spade a spade if there’s a ‘reckless disregard of the truth.’

Excessive deference can be corrosive to the democratic value of checks-and-balances.

As Dean Baquet, the executive editor of The New York Times, told Chuck Todd of NBC’s Meet the Press in a New Year Day broadcast, ‘The way to deal with all questions about journalism is more journalism and good journalism, deep, investigative reporting and deep questioning reporting.’

Leave a reply