Umesh Malhotra an IITian working in California became aware of the strong focus and impact of books on children at a very early age, thanks to US activity-based libraries.

When he decided to return to India, he promised his seven-year-old son that he will recreate a similar, more novel experience not just for him but for many more children.

However, things were different when he arrived.

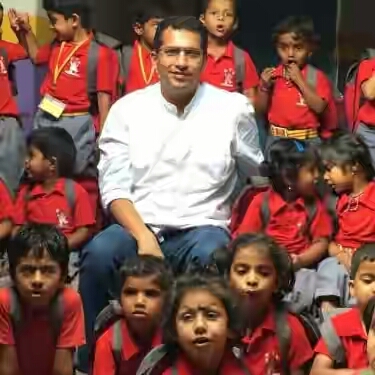

Umesh Malhotra, founder of Hippocampus Learning Centres, braced all challenges for over a decade and continued to refine his model. From urban libraries to rural pre-primary school centres, Umesh has come a long way.

Today, he runs 285 primary school centres in Karnataka alone, benefitting over 11,000 children.

In another three months, he will be opening 30 new centres and venturing into a new state — Maharashtra.

In 2003, Umesh built the first library in a sprawling 5,600-sq ft plot he owned in Koramangala, Bengaluru.

The library boasts of an envious collection of children’s movies and hosts reading sessions and other fun activities such as treasure hunts, movie screenings, quizzes and trips.

Three years later, after a conversation with Rohini Nilekani (wife of Nandan Nilekani) and visits to a few rural schools, Umesh decided to expand his reach by including the bottom of the pyramid.

His ultimate aim was to be able to motivate every child, irrespective of geographical location, and inculcate the habit of reading without force or intervention.

So, he started the ‘Grow by Reading’ programme, which was designed to address different reading interests, keeping in mind varying reading proficiencies as well.

The intervention has identified six reading levels and every child was assessed and assigned a certain level, allowing them to choose books that they can easily read as well as gradually progress by incorporating higher level books.

For the first seven years, Umesh focussed on building libraries right from the ‘Motorcycle’ to the ‘Bicycle’ segment (rich to poor).

But was it enough? Definitely not.

According to Pratham’s study, 45 percent of the children between the age group of seven and 10 from government schools and 24 percent in private schools can’t read words, leave alone sentences, with ease.

And in an economy where English is slowly emerging as the language of choice, it’s only natural for parents to have this as one of their top expectations — one which currently isn’t met in the Tier III and IV markets.

Umesh started toying with the idea of setting up preschools for children across rural India.

He began experimenting again — with pre-primary schools, after-school tuitions for Class I to V, and a programme for Class IX and X students to help them pass their board exams.

But the results of the preschool learning centres were the most effective. So Umesh opened 17 Hippocampus Learning Centres in 2011 in Mandya, Karnataka. He affirms, “the idea was to open pre-primary schools in areas which one can’t even find on the map, the Tier IV markets.”

He further adds, “And the second crucial aspect was to train and employ people from this region, primarily women in order to give them the benefit of organised employment.”

According to Umesh, this is a market that makes up for 60 percent of India’s population. Yet, the irony is that it’s most neglected as for development.

Today, Umesh runs over 300 centres, with 700 teachers who benefit 11,000 preschoolers.

Umesh’s preschool programme is a three-year-long programme designed for 2.5- to 6-year-olds, wherein they are introduced to English and Maths. He says, “In rural India, education begins only in the first grade. The government-run anganwadis act as day-care centres and don’t have outcome-based learnings at the core of it. HLC tackles this by getting preschoolers ready to enter the formal education system.”

HLC’s internal impact assessment has shown that by the end of the three-year programme, at least 85 percent of the children are able to read and write simple sentences in English and Kannada as well as perform single-digit Maths problems.

Umesh also has a training academy for teachers.

But, the most interesting and powerful aspect of HLC is its scale — from 17 to 285 centres in less than five years.

It’s been well-established that HLC has achieved impact in terms of learning outcomes as well as generating employment for rural women. But the biggest challenge ahead was scale. After all, Umesh has set himself on ‘Mission Finland’ — to bring preschool education to as many students in India as the population of Finland.

So, he started the partnership model.

He says, “There are enough individuals in our nation who are thinking about the prosperity of their villages, but have little support. We leverage on these individuals by hand-holding them into rural entrepreneurship in a profitable, sustainable and scalable fashion — keeping outcome-based learning at the heart of it.”

Nagendra Mali from Karnataka’s Haveri village is one such entrepreneur.

He has over two decades of experience in micro-financing and was also running a public school for almost nine years. But when he heard of Hippocampus, he decided to add the preschool wing to his school and after seeing its impact of it, he decided to start five more schools.

He says, “In our taluk there is only one micro-finance branch but Hippocampus has eight branches. This is a testimony of the untapped potential and demand in the rural market.”

Nagendra has managed to open two schools as of now and hopes to continue expanding the HLC network.

The cost of opening a preschool franchisee ranges between Rs 2 to 2.5 lakh, wherein HLC helps with teacher recruitment and training, knowledge, expertise and assessment. The fees ranges between Rs 3,000 and 8,000 per annum depending upon the level.

According to CRISIL, the preschool industry has been growing at a five-year CAGR of 20 percent and was standing at Rs 99 billion last year.

By 2020, the estimate is that this industry will be worth Rs 220 billion. However, Tier IV markets remain a challenge and HLC has been able to scale up as the modest input costs has been a prime factor.

Competitors such as Euro Kids, Kidzee, Shemrock and other chain of play schools require anywhere between Rs 10 to 20 lakh to set up one centre.

Furthermore, there are a host of restrictions in place, such as having a minimum of 1,000 to 2,000 sq ft space, expensive monthly/quarterly fees, revenue-sharing model, branding costs etc. This makes it difficult to start generating profits early on.

HLC has seen that on an average, it takes a year to break-even. By the second year, entrepreneurs are on their way to making profits and in the third year, “they are soaring high.”

Today, 65 percent of HLCs are making profits, a sure sign that the model is working.

He says, “Eventually, we are looking at 15 –to 20 percent of the children of a village to join HLC.”

The company wants to expand to 5,000 centres in another five years. But beyond that, Umesh wants to break a myth,

“I want everyone to really believe that high-quality education can be provided to the poorest communities at affordable costs.”

Leave a reply