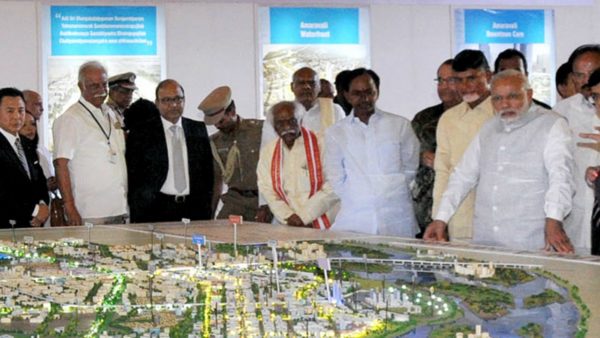

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone for a new capital in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh in 2015. But three years later nothing has been built in Amaravati, which was touted as a city that could “make India proud”, reports Sriram Karri.

The state was forced to look for a new capital after it was split in two to create India’s 29th state, Telangana. The current capital Hyderabad went to the new state, although both states were to share it for 10 years.

The plans for Amaravati were ambitious to say the least. The city was to be developed over 7,500 sq km (2,895 sq miles) over the next 10 years, and it was envisaged it would be 10 times bigger than Singapore.

The chief minister of Andhra Pradesh, N Chandrababu Naidu, who was widely held to be responsible for converting Hyderabad from a sleepy historic town into a global software destination during his previous term as chief minister between 1995 to 2004, was brimming with confidence.

He had proposed a scheme where farmers voluntarily surrendered their land in exchange for developed land in the city.

But today, nothing has been built on the vast amount of land procured from farmers. Even roads and basic infrastructure like drainage and power lines are yet to be put in place. Barring an interim government complex with a Legislative Assembly and a Secretariat, there is nothing.

The big reason has been Mr Naidu’s personal obsession with grandiose designs and obsessions for historic legacy.

First, the government chose Maa Ki, an architects’ firm from Japan, to create designs. After a year of changes and upgrades, their designs were rejected; and the project was handed to London-based Foster + Partners, early last year.

Thy are known for designs and projects globally, especially prestigious structures like the London headquarters of Swiss Re and the German parliament, but the chief minister remained unimpressed with their models for the Government Administrative Complex.

With not even a design for the first of the buildings in three years, Mr Naidu approached filmmaker Rajamouli, whose mythological epic, Bahubali, set in a fantastical city, was a huge hit. He was roped in to go to London and advise the architects on finer design elements. The movie director confessed to his own inability to play a role in designing a city but Mr Naidu’s critics say he ploughed on regardless.

Olympic venue?

Having allied with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Mr Naidu had hoped Mr Modi would fund the Amaravati project besides giving Andhra Pradesh a special category status so that tax concessions would have investors rushing to the state. A few months ago, Mr Naidu withdrew support for the Modi-led government and changed his political position overnight to oppose the BJP at next year’s elections.

Mr Naidu then approached the World Bank for a loan of 38 billion rupees ($535m; £411m) and India’s building authorities for another 75 billion rupees. All borrowing failed to match the huge capital costs needed to even start building the city of his dreams.

Meanwhile, the government of India capped its funding for Amaravati at 15 billion rupees, barely adequate for building the governor’s house, high court and legislative assembly besides a few other administrative offices.

Given the state’s poor financial condition, Mr Naidu had no option but to find creative ways to raise funds.

One such experiment was a crowd-sourcing effort to raise emotional equity around the city. Dubbed “My Brick, My Amaravati”, the government asked people worldwide to buy e-bricks at 10 rupees. After several campaigns to promote it, all it had was about 227,000 donors buying 5,708,905 e-bricks.

In a first of its kind, the cash-starved state government issued high interest-assured long-term Amaravati bonds on the Bombay Stock Exchange and raised 20 billion rupees. At a grand function, where the bonds were oversubscribed 1.53 times, Mr Naidu announced he planned to raise an additional 100 billion rupees soon.

So buoyed up was Mr Naidu by the response by institutional investors to his bonds, that he outlined a grand vision.

“I want to host the Olympics at Amaravati in the near future,” he said.

‘Flood risk’

But the first master plan created for Amaravati by a Singaporean firm had described the location to build the capital as “low to medium flood prone” and suggested a water network mitigation within the proposed city.

India’s environment body, the National Green Tribunal (NGT), had also accused the state government of not considering “ecological and environmental aspects of the project”. But it eventually gave a conditional nod to the proposed development.

“Amaravati is an environmentally unsustainable project and a flood risk,” says Prof Ramachandraiah Chigurupati of the Centre for Economic and Social Studies.

“In a zone characterised as low-lying plains with fertile agricultural land, floods will be a feature. The state has been hit by several cyclones over the years.

“In times of global warming, which leads to intense bursts of heavy rains, an entire city could be inundated within hours, leading to massive destruction as witnessed in the recent cyclones in Kerala.”

Sriram Karri is author of the bestselling, MAN Asian Literary Prize longlisted novel, Autobiography of a mad nation, whose next book will be One Farmer Less.

Leave a reply