Indian agriculture has had a terrible year.

Unseasonal rains hit north India in February and March. The monsoon rains were inadequate in several states. Then floods hit south India in November and December.

Vast stretches of farmland lie devastated and the effects are showing up in the countryside where in states like Uttar Pradesh, as Scroll.in reported, the poor are eating rotis made of weeds.

In the first week of December, the agricultural minister Radha Mohan Singh told Parliament that deficit rainfall in the monsoon had affected crops spread over 19 million hectares in seven states.

The minister also said the planting of the winter crop was down by 18%.

In some parts of Madhya Pradesh, the water levels are so low that the administration has banned the drawing of water from public reservoirs for irrigation.

It might not be long before the cities feel the pinch.

Rise in food inflation

A failed crop doesn’t affect farmers alone – it pushes up the price of food for everybody.

As Business Standard reported this week, there has been a steady decline over the last year in the wholesale price index which reflects the price of goods traded by companies. But the consumer price index, which shows the price of goods available to consumers, remains high, primarily because of the rising prices of food.

This week, in a written reply to a question in Parliament, the food minister Ram Vilas Paswan put out data on the retail prices of food in the month of December over the last four years.

The data showed a shockingly steep rise in the price of arhar and urad dal.

The crisis of dal

India is one of the biggest consumers of dal in the world. Its large vegetarian population depends on dal for its protein intake. But the country has not been able to incentivise farmers into growing more dal. While the government purchases foodgrains in large quantities for its public distribution system, it does not buy dal on the same scale. The minimum support price it offers to farmers for dal is not much higher than the market price. This has ensured that farmers with irrigated land prefer growing grains. Key varieties of dal are grown on rainfed land, subject to the vagaries of the monsoon.

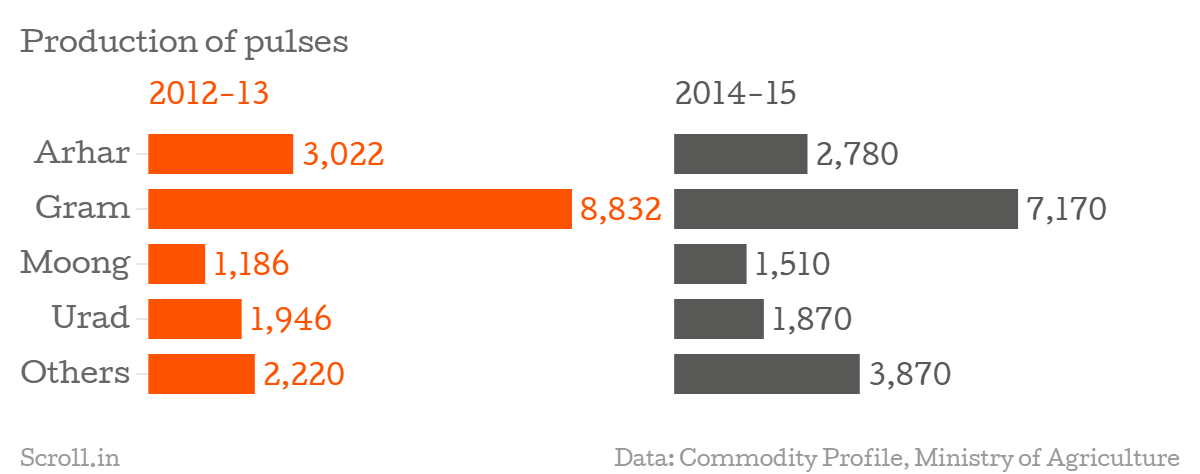

Given adverse weather conditions, the production of dal declined from 19.25 million tonnes in 2013-’14 to 17.20 million tonnes in 2014-’15, the food minister told Parliament.

But this doesn’t reveal the extent of the crisis. Disaggregated numbers show how much more steeply the production of the more popular varieties of dals has declined.

To insulate consumers from further price shocks, the government had decided to create a buffer stock by procuring 1.5 lakh tons of dal this year from farmers, the food minister said.

Debate on drought

The scale of the crisis is barely reflected in debates, whether on prime time news on television, social media conversations, or even within the Parliament.

On December 7, just past 2 pm, a debate began in Lok Sabha on the drought situation. Five MPs spoke on the subject. Most wanted to know what the government was doing to provide relief to farmers. Around 4 pm, the chairperson moved on to another subject, saying the debate would continue later.

But that never happened.

The same day, a court in Delhi issued summons to Congress leaders Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi in the National Herald case. Since then, Parliament has been caught in political bickering.

It has fallen on the Supreme Court to bring back attention to the issue.

On December 15, a week after the aborted debate in Lok Sabha, responding to a petition filed by activists, the Supreme Court issued notice to the central government along with 11 states, asking them to outline the steps they were taking for providing relief to farmers and ensuring the poor had access to food.

The central and state governments have time to respond by January 4, 2016.

Leave a reply