As India’s most restive region stares down the abyss of what a commentator calls another “hot summer of violence”, the doom-laden headline has returned with a vengeance: Is India losing Kashmir?

Last summer was one of the bloodiest in the Muslim-dominated valley in recent years. Following the killing of influential militant Burhan Wani by Indian forces last July, more than 100 civilians lost their lives in clashes during a four-month-long security lockdown in the valley.

It’s not looking very promising this summer.

This month’s parliamentary election in Srinagar was scarred by violence and a record-low turnout of voters. To add fuel to the fire, graphic social videos surfaced claiming to show abuses by security forces and young people who oppose Indian rule. A full-blown protest by students has now erupted on the streets; and, in a rare sight, even schoolgirls are throwing stones and hitting police vehicles.

Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, who leads an awkward ruling coalition with the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), rushed to Delhi on Monday to urge the federal government to “announce a dialogue and show reconciliatory gestures”.

Reports say Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Rajnath Singh told her that they could not “offer a dialogue with separatists and other restive groups in the valley” while fierce violence and militant attacks continued.

Former chief minister and leader of the regional National Conference party Farooq Abdullah warned India that it was “losing Kashmir”. What Mr Abdullah suggested was unexceptionable: the government should begin talking with the stakeholders – Pakistan, the separatists, mainstream parties, the minority Kashmiri Hindus – and start “thinking of not a military solution, but a political way”.

With more than 500,000 security forces in the region, India is unlikely to lose territory in Kashmir. But Shekhar Gupta, a leading columnist, says that while Kashmir is “territorially secure, we are fast losing it emotionally and psychologically”. The abysmal 7% turnout in the Srinagar poll proved that “while your grip on the land is firm, you are losing its people”.

So what is new about Kashmir that is worrying India and even provoking senior army officials to admit that the situation is fragile?

For one, a more reckless and alienated younger generation of local youth is now leading the anti-India protests. More than 60% of the men in the valley are under 30. Many of them are angry and confused.

Ajaz, a 19-year-old student in Budgam, told me that hope had evaporated for his generation “in face of Indian oppression” and he and his friends did not “fear death”. When I took him aside after a while to ask about his ambitions in life, he said he wanted to become a bureaucrat and serve Kashmir.

“It is wrong to say that the Kashmiri youth has become fearless. He just feels alienated, sidelined and humiliated. When he feels like that, fear takes a backseat, and he becomes reckless. This is irrational behaviour,” National Conference leader Junaid Azim Mattoo told me.

Secondly, the new younger militants are educated and come from relatively well-off families.

Wani, the slain militant who headed a prominent rebel group, hailed from a highly-educated upper-class Kashmiri family: his father is a government school teacher. Wani’s younger brother, Khalid, who was killed by security forces in 2013, was a student of political science. The new commander of the rebel group, Zakir Rashid Bhat, studied engineering in the northern Indian city of Chandigarh.

Thirdly, the two-year-old ruling alliance, many say, has been unable to deliver on its promises. An alliance between a regional party which advocates soft separatism (PDP) and a federal Hindu nationalist party (BJP), they believe, makes for the strangest bedfellows, hobbled by two conflicting ideologies trying to work their way together in a contested, conflicted land.

Fourthly, the government’s message on Kashmir appears to be backfiring.

When Mr Modi recently said the youth in Kashmir had to choose between terrorism and tourism, many Kashmiris accused him of trivialising their “protracted struggle”. When BJP general secretary Ram Madhav told a newspaper that his government “would have choked” the valley people if it was against them, many locals said it was proof of the government’s arrogance.

Fifth, the shrill anti-Muslim rhetoric by radical Hindu groups and incidents of cow protection vigilantes attacking Muslim cattle traders in other parts of India could end up further polarising people in the valley. “The danger,” a prominent leader told me, “is that the moderate Kashmiri Muslim is becoming sidelined, and he is being politically radicalised.”

The security forces differ and say they are actually worried about rising “religious radicalisation” among the youth in the valley. A top army official in Kashmir, Lt-Gen JS Sadhu, told a newspaper that the “public support to terrorists, their glorification and increased radicalisation are issues of concern”.

One army official told me that religious radicalisation was a “bigger challenge than stone pelting protesters”. He said some 3,000 Saudi-inspired Wahhabi sect mosques had sprung up in Kashmir in the past decade.

Most Kashmiris say the government should be more worried about “political radicalisation” of the young, and that fears of religious radicalisation were exaggerated and overblown.

Also, the low turnout in this month’s elections has rattled the region’s mainstream parties. “If mainstream politics is delegitimised and people refuse to vote for them, the vacuum will be obviously filled up with a disorganised mob-led constituency,” Mr Mattoo of the National Conference said.

In his memoirs, Amarjit Singh Daulat, the former chief of RAW, India’s spy agency wrote that “nothing is constant; least of all Kashmir”. But right now, the anomie and anger of the youth, and a worrying people’s revolt against Indian rule appear to be the only constant.

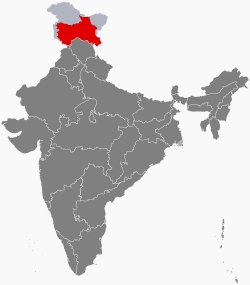

Five things to know about Kashmir

India and Pakistan have disputed the territory for nearly 70 years – since independence from Britain

Both countries claim the whole territory but control only parts of it

Two out of three wars fought between India and Pakistan centred on Kashmir

Since 1989 there has been an armed revolt in the Muslim-majority region against rule by India

High unemployment and complaints of heavy-handed tactics by security forces battling street protesters and fighting insurgents have aggravated the problem

Leave a reply