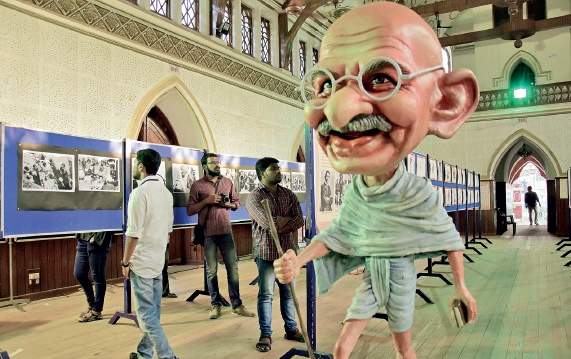

Seventy years after Mohandas Gandhi died, people have come to recognise his assassination (or the argued causes behind it) as a fault-line between competing ideas of modern India.

Gandhi’s assassination still has a bearing, not only on Hindu-Muslim relations and the “Secularism vs Hindutva” debate, but also on the very nature of what it means to be a Hindu in the 21st Century. However, bitter disputes on all these issues tend to obscure a more vital and urgent question. Can non-violence be a viable and practical ideal or the basis of a society?

To his last breath, Gandhi’s answer to this question was an unwavering “yes”. But today, most young people view Gandhi’s confidence in non-violence as a well- meaning pipe dream at best, and a delusional state of mind at worst.

However, it is futile to dismiss this scepticism about non-violence as mere ignorance or a lack of moral fibre. Instead there is a need to do three things:

• Examine the case for violence

• Review if Gandhi’s idea of “peace armies” has any merit

• Ask if ordinary people can be compassionate towards perpetrators of violence — which is the essence of Gandhian non-violence.

The case for violence

The heartbreak Gandhi suffered in his final days due to communal violence, and ultimately his assassination, has been used by critics of non-violence as decisive evidence that violence is more powerful. After all, isn’t the history of societies across the world replete with examples of violence as the preferred method for overthrowing power structures and dealing with communal conflicts? This partly explains why, according to the peace group International-Alert, approximately 1.5 billion people, 20 percent of the world’s population, live under the threat of large-scale organised violence.

Not all the violence is a consequence of passions running amok. Much of it has a philosophical sanction. For instance, when writing in support of colonised people, French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre argued that violence is a “cleansing force” that provides dignity and restores self-respect when the oppressed rise up against their oppressors.

In post-Independence India, a wide range of activists, struggling for social and economic justice, emphatically rejected non-violence because they saw it as the method of those who are themselves well-paced and want to maintain the status quo.

This is why Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Zedong remains the inspiration for an insurgency movement that still operates in approximately 60 districts of India. The slogan of these rebels, since the time of the Naxalbari peasant revolt in 1967, is Mao’s famous declaration that political power flows from the barrel of a gun.

Even identity based organisations of varied hues — be it Christians, Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Sri Lankans, Tamils and so on — have claimed violence to be a necessary and legitimate tool.

Over the last 15 years, even in the World Social Forum, an international network of political action groups and NGOs, there has been bitter disagreement about including non-violence as one of the basic principles on which all participating groups agree. Many participants in the forum feel that it is self-defeating for the oppressed to adopt non-violence.

Those who want to grant legitimacy to violence are not merely being pragmatic or tactical. Their argument is that rage and violence are natural human tendencies and to cure humans of them would be to dehumanise or emasculate them.

However, it is equally true that while votaries of violence tend to focus on destruction of the old, the advocates of non-violence are concerned with creating something new. Perhaps the most powerful voice on this theme in academia has been of American political theorist Hannah Arendt’s.

Arendt’s key argument is that what flows from the barrel of a gun is not power but obedience. Arendt wrote, “Violence and power are opposites… Violence appears where power is in jeopardy, but left to its own course its end is the disappearance of power…. Violence can destroy power; it is utterly incapable of creating it.”

Being felled by an assassin validated this conviction: To have kept armed guards or to have surrendered to the majority community’s demand that he shares their hatred for Muslims would have been a defeat.

However, in order to explore if Gandhi’s conviction could be the basis of countering the proliferation of hatred and hate crimes in our times, it is important to re-visit the story of the Shanti Sena.

Peace Armies

In March 1948, just weeks after Gandhi’s assassination, Congress leaders gathered for a conference to take stock of the post-Gandhi reality. At this gathering, Rajendra Prasad, then president of the Congress, called for the formation of ‘Shanti Seva Dals’ — an idea that Gandhi had often spoken about but had never been able to work on.

A Shanti Seva Dal, Prasad wrote, is not intended to be a police force or a body of volunteers that has to run around suppressing riots and disturbances. Instead it would have to always be at work, creating “an atmosphere of peace and goodwill so that communal riots and disturbances may not occur at all and, if they unfortunately do occur, to throw itself between the fighting forces and thus prevent or at any rate reduce the intensity of the clashes”.

This idea of “peace warriors” willing to risk life and limb to prevent violence is not new. Apart from Gandhi, this concept had been developed by European and American pacifists throughout the early 20th Century. When the Shanti Sena was finally formed in 1950, with Vinoba Bhave as its president, the gaze of war resisters and advocates of non-violence across the world was on this experiment.

“Make a very natural beginning,” Bhave told the first Shanti Sainiks. “Take a day off in a week and go out as if for an excursion.… Mix with the people there, make friends with them. Interest yourself in their joys and sorrows.… Moving among the people is the initial stage of the programme before Shanti Sena. The rest will follow automatically.”

The Shanti Sena went on to operate intermittently for three decades. Among its successes were the Nagaland Peace Mission and Chambal Peace Missions. Shanti Saniks were able to intervene successfully to quell or reduce violence in various situations — language riots in Gujarat in 1965 and communal flare ups in Rourkela in 1964, Agra in 1968 and Ahmedabad in 1969.

During communal disturbances, Shanti Sena worked at three levels: To remove tensions that led to the unrest without resorting to police or courts; to intervene in actual outbreaks of violence at the risk of death; and do relief work among the victims after the riot has subsided.

Votaries of the Shanti Sena were acutely aware of the criticism from those who view violence as a legitimate weapon in the quest for social justice.

Shanti Sena’s work in India became the inspiration for the formation of Peace Brigades International, now a global organisation supporting human rights workers in situations of civil war and other forms of violent conflict.

Unfortunately, the Shanti Sena did not develop as originally envisioned — as a decentralised network of dedicated, locally anchored peace-builders embedded within communities. Australian scholar Thomas Weber wrote in his detailed study of the Shanti Sena that it was undermined by over-centralisation. The Shanti Sena endeavour also did not survive beyond the lifetime of stalwarts who made it possible — Vinoba Bhave, Jayprakash Narayan, Narayan Desai.

Limitations of the Shanti Sena experiment can be used as evidence to dismiss its core premise that oppressors and perpetrators of violence can be won over and made to understand the nature of their actions.

As Gandhi repeatedly said about perpetrators of violence, “Who can dare say that it is not in their nature to respond to the higher and finer forces? They have the same soul that I have.”

Was Gandhi’s faith misplaced? Johan Galtung, the veritable ‘father’ of Peace Studies, has concluded that Gandhi’s methods worked in situations where the conflict is vertical and violence is structural. Gandhian non-violence, Galtung argued, does not work as well in situations of conflicts within society when ‘equally autonomous actors’ or ordinary people attack each other.

There is ample evidence to validate this assessment. Let us instead look at evidence to the contrary that tends to be under-reported.

Compassion for perpetrator

Vijay Pratap, a veteran Gandhian socialist political activist, was representing a candidate at a polling station when an altercation broke out with the opposing candidate’s supporters. One of Pratap’s colleagues was beaten to the ground and the lathi blows continued. Suddenly, Pratap flung himself on his fallen colleague to save him from the blows by taking them upon himself.

The assailants were so stunned, they backed off. Years later Pratap recalls that what the assailants expected was a violent retaliation from the team members of the man who was being beaten.

Pratap’s action was due to his training during the JP movement of the 1970s which popularised the slogan ‘hamla chahe jaisa hoga, haath hamara nahin uthega’ (no matter how we are attacked, our hand will not rise in retaliation).

Even a cursory review of the work of peace and non-violence activism across the world shows that such incidents are not rare. Such unarmed selfless actions do not always cause the assailants to withdraw but neither does violent retaliation always get the desired result.

How can this knowledge help inspire and empower those citizens who are deeply disturbed by the proliferation of violence and open expression of hatred — not just by organised groups, but also by their peers in daily life?

First and foremost, you don’t have to be a saint, or a full-time activist, to listen and look for the hurt or angst that causes people to slip towards hatred, prejudice and violence.

This requires an intense introspection by advocates of justice and peace. It calls for an ability to not react to the hatred and instead listen for the concern behind the complaint. This opens up doors and creates new possibilities for reconciliation and cooperation. By contrast hating the haters only locks everyone into a cycle of conflict and violence.

Those who find this implausible could refer to a new book Radical Transformational Leadership by Monica Sharma who worked with the United Nations for over 20 years and successfully applied this approach in a wide variety of conflict situations.

What Sharma shares in her narrative is also validated by a wide range of groups using theatre and other techniques to initiate dialogue to overcome conflicts within communities. For example, Mohalla Committees formed in Mumbai as a response to the violence in that city in 1992-93, are still working with moderate success.

Recently a group of activists, including Aruna Roy and Harsh Mandar, announced an effort to build ‘Insaaniyat and Aman Citizen Councils’ at the district level across India. In an increasingly polarised society, the task of these committees will be challenging enough.

If these councils take Gandhi seriously, then that raises the bar still further, for Gandhi would have them reach out to the “rowdy elements, befriend them… neither neglect them nor pander to them”.

To do that requires the faith that everyone can be enabled to strive to be freed from the toxicity of hate and rage. That we, who see ourselves as champions of justice and peace, can approach the perpetrator not as the ‘enemy’ but as someone in need of help.

Rajni Bakshi is the author of ‘Bapu Kuti: Journeys in rediscovery of Gandhi’

Leave a reply