If Saadat Hasan Manto were to go book shopping today, he would have thumbed his nose at the whole Self-Help Section.

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: ‘Scam!’ Manto would have grunted, ‘Isn’t that a narrowing of your imagination? ‘Numbering’ the ways in which people may be considered effective.’

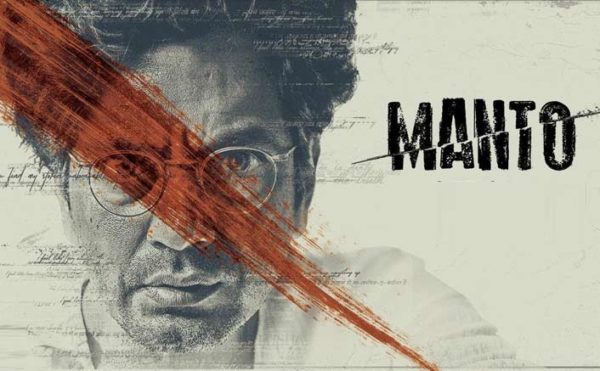

Among the many privileges of Nandita Das’ Manto, one that it clearly grants is the privilege to visualise how its subject may have reacted to the developments in the modern world.

For example, I assume Manto would have thought Social Media a harmless, kitschy vice.

I am guessing he would have enjoyed memes; would have even offered poetic variations on many of them.

He would have had his reservations about Global Warming — ‘too easy a theory’ is what he would have probably said about it.

He would be happy that violence against women is being fervently discussed but would also be distressed by our thinking that solving such crimes ‘judicially’ would make this a state of honourable men.

If anything, Manto believed that we are all equally capable of ‘small acts of kindnesses’ and ‘grand horrifying feats’ — and almost nothing in between.

This is what Nandita Das achieves through this film.

n her genuine fascination for Saadat Hasan Manto, she turns the man into a timeless idiom for the ambitious, opinionated artist.

In following the writer’s life from mid-1940s to 1951, Das isn’t playing a mere social chronicler here. She approaches Manto like how we try to piece together the various stories of a heroic great-grandfather about whom we may have heard a lot but weren’t lucky enough to meet.

Das has taken on this subject because she believes that she is a child of Manto. (In understanding Manto, she is also examining her own impulses).

And it is this belief of Nandita Das that gives her highly intelligent piece of work, its true feeling.

Das reveals to us Manto’s sharpness (she isn’t afraid to let him utter whistle-worthy lines), but she also takes us to the source of that sharpness and then shows us the ways in which artists such as Manto are naturally vulnerable.

In a scene set inside an Irani restaurant, Manto and Ismat Chughtai (Rajshri Deshpande makes Chughtai seem worldly and yet in a zone of her own) argue for their respective crafts: He always knows what happens to his characters behind closed doors; she wouldn’t even tell you what’s beneath a quilt.

They are passionate critics of each other — later Chughtai writes to Manto when he is in Pakistan and the letter opens with the salutation: ‘Manto my friend, my enemy.’

Chughtai and Manto tussle, but unknown to their respective geniuses, there are other tensions bouncing around.

His friends want to know why Manto wouldn’t write about the Freedom Struggle and instead chooses to focus all his attention on the plight of women.

Manto doesn’t care about such questions because he knows better. He sees the celebration of the oncoming Independence as the Social Equivalent of a Bestselling Novel — a dream being put up for sale.

If he squats over a chair and writes feverishly about strong, complex women — with a pencil in hand and a quarter bottle of alcohol close at hand — it is because he legitimately finds women more interesting than men.

And Nandita Das demonstrates this through small scenes.

Standing near the graves of both his parents, Manto prays only for his mother’s soul (He blames his father for giving him all his useless fears); and at one point, wonders if his feet are turning ‘feminine’.

‘That would be unwelcome,’ says Manto with a smile.

Critically speaking, Saadat Hasan Manto was an Easterner with a rather ‘Western’ sensibility.

He saw Indian realities with eyes trained by Western Art (This is what makes his work so fresh: you could argue that Satyajit Ray and Bhupen Khakhar also worked on similar cues).

Das gives us the philosophy that powered Manto’s art (‘Either everything in life matters or nothing’) and then in a heartbreaking scene, illustrates how sacred philosophies can be rendered impotent in an instant.

When Manto is facing trial on obscenity charges for his short story Cold Meat, poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz appears in Manto’s defence.

Manto considers Faiz to be a kindred spirit. He is looking forward to Faiz not just defending him, but also extolling his virtues as a writer.

Sure, Faiz Ahmed Faiz defends Manto.

‘Cold Meat isn’t obscene,’ says Faiz, but he stops to add this: ‘Neither does it meet the standards of literature.’

Manto may have died a thousand deaths before cirrhosis finally claimed him, but Faiz’s appraisal of his work in court was certainly his most famous death.

It is a sledgehammer of a scene, but Nandita Das does not hold it for effect and Nawazuddin Sidiqqui achieves a career first at portraying shock that is completely unplanned.

Sidiqqui usually plays hustlers for whom ‘shock’ is just yet another weapon in their Hustler’s Artillery.

However, when his characters are honestly wounded, they move onto the next moment (Remember that scene in Badlapur, where, upon realising that Vinay Pathak’s Harman maybe avoiding him, Siddiqui’s Liak suddenly turns all businessman-like?).

Here, Siddiqui seizes his moment of hurt through Nandita Das’ quick cut to his face.

Manto is supposed to lord over the movie, but Siddiqui creates out of him a broken idol — he plays him like a man with too many opposing feelings inside him.

He is Manto the resolute artist, but he is also Siddiquesque in his commitment to the interweaving energies of each moment.

To Nandita Das’ credit, she, for the most part of the film, allows Siddiqui to not make Manto, one-toned.

However, she is also unyielding in her vision of Manto as a writer who was forever ‘on the page’.

Look how beautifully Das sets up that scene where Manto tells his little daughter a story.

He makes her sit on his lap and after blurting out three kingdoms with such names as Nani, Nahani and Bisaula, proceeds to construct a narrative filled with circumlocutions which are eerily like those in Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories.

If there is a truth about writers, it’s that the ambitious ones never put their pens down — and Nandita Das knows this fact.

She makes even Manto’s by-the-way stories works of art.

Also interspersed throughout the film are dramatisations of Manto’s numerous short-stories; but the cinematic masterstroke is in Nandita Das’ decision to insert the stories as if they were outgrowths of Manto’s everyday consciousness.

Manto’s characters are shown to almost ‘meet’ him — in a lane, at a camp, or at a halfway house — and this artistic choice intensifies for us Manto’s choice of characters.

Manto’s characters were ordinary people who did highly poetic things innocently — his stories were in a sense about poets who were unaware of their own talents.

The climaxes of Manto’s stories suggested deeper, unsaid tragedies and the film is bookended by two such stories: The silently devastating Ten Rupees and the clamorously haunting Toba Tek Singh.

Nandita Das is shrewd about her reconstructions of the 1940s.

She is clearly working on a small budget and so picks her battles with ‘Period’ wisely.

The question that the director seems to be asking herself is: How did the times bear on the story and its characters?

Das understands that Bombay had a particular ‘style’ back then; there were things that it considered ‘cool’.

It is this style that she wants to bring to you — more than sartorial specifics or architectural details.

Smoking in railway stations was permitted.

Baby Touch was a popular brand of facial hair remover.

At an Independence Day celebration party, ghazal is rendered to the beats of slow jazz.

This is a party that Ashok Kumar throws; where Naushad is called out between the clicking of glasses; and where K Asif beseeches Manto to review his latest script.

Manto collects his fees for the review and then declares the script to be terrible.

Asif, unhurt, announces Mughal-e-Azam right there.

The party feels like a colliding of stars, but without the sound of evident names-dropping.

Actually, this Jamesian subtleness is a big part of Nandita Das’ sensibility.

Das’ camera isn’t fluid, but she creates great density within scenes.

When she adds foregrounding elements (such as a worker on a film-set walking into a frame with a ladder); or when she makes faces emerge magically (like that shot of Manto being illuminated by the spark of a match); or when she meticulously adds to a scene those ‘little sounds’ (like the precise sound of tobacco burning as Manto smokes a cigarette) — they become dramatisations of the movie’s major theme: the insane, ambitious artist who works primarily to please herself and only then the world.

In a way, the distance of Manto’s story gives Nandita Das an atmosphere that saturates many other themes and concerns.

When Manto leaves Bombay for Lahore, the graves of his parents and his dead son don’t accompany him.

It is true: Boundaries are not for the dead to cross.

Another idea that is silently conveyed: It is not a crime to love the city that one lives in more than one’s country. (This is true of most big cities of the world — Londoners love London more than they love the rest of England; New Yorkers love New York more than they do America).

Manto’s Bombay (As he calls it: ‘The city that asks no questions’) is a city that inspires a young Muslim man who is being coaxed into moving to Pakistan, to say: ‘My watan is Bhendi Bazaar.’

Patriotism is a many-hued thing; and sometimes the love you feel for a city, for a locality, for a lane even, may just be a lot stronger than your love for a nation.

That said, it’s his beloved Bombay that Manto eventually leaves — and with it also the graves, the café societies and some of his closest friends: including an upcoming actor/later-year star Shyam Chadda (played by the fluid Tahir Raj Bhasin, whose eyes constantly seem like they are trying hard to mask his inner calculations).

Manto and Shyam’s camaraderie is in the tradition of the great friendships we have seen at the movies and Nandita Das doesn’t thankfully hold back the juices.

She consciously plays it broad.

The period setting makes the Manto-Shyam friendship (with their running jokes) seem like an elegy to lost time.

The parts of Manto’s life that Nandita Das finds impressive, she assembles to construct the man and an idiom. However, it is those parts of Manto that don’t fit the impressive jigsaw that Das glides over using a mournful score in the background.

Because the wonderful Rasika Dugal (playing Manto’s wife Safia) isn’t given enough contrapuntal shots in the Lahore section, you don’t feel the crumbling of the marriage as potently as you should have.

In the Bombay section, Das externalises Manto’s mindscape, but when the action shifts to Lahore, with Manto starting to live more and more inside his own head, the story too loses its sense of place and time.

Nandita Das, one gets the feeling, could not quite assent to the fact that the social alienation that Manto felt in Lahore was also intricately linked to his artistic temperament.

To think of it, this not-so-impressive part of Manto is like the characters he wrote about: characters who lived on the margins, but who were enlivened by Manto’s vision and his pen. These characters seemed magical because Manto wrote about them.

If Manto, the film, falls short of being a masterpiece, it’s ironically because Nandita Das the filmmaker does not quite crack the Manto code herself: she doesn’t quite see her subject with the same wholeness that Manto saw his people.

This imperfection in the film, in a way, becomes the greatest tribute to Manto.

Leave a reply