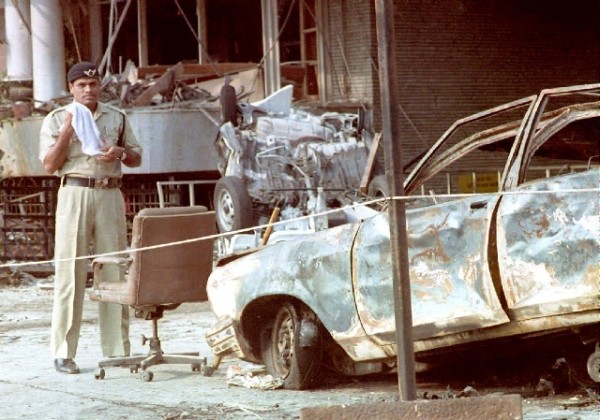

There are innumerable ways in which we can remember March 12, 1993, the day on which 20 years ago bomb blasts rocked the city of Bombay – which hadn’t yet become Mumbai – killing 250 and injuring another 750. We could say that it marked the advent of urban terror of the most frightening kind in India, that it was the harbinger of the devastation Pakistan’s ISI could wreck, that it underscored the firepower the underworld could command, hitherto much romanticised in the popular culture.

However, a more telling way of commemorating March 12, 1993 would be to fathom the Indian state’s inclination to crush terrorism and yet, ironically, condone communalism. It is ironical because both terrorism and communalism, despite the definitions distinguishing the two, are predicated on harnessing violence in the pursuit of political goals. One deploys dangerously armed groups to perpetrate bloodshed, the other murderous mobs which too possess weapons, though less sophisticated and deadly in comparison.

The contradictory response of the Indian state to these types of terror can be gleaned from its attitude to the serial bomb blasts and the grisly Bombay riots of 1992-1993, which was sparked off as a consequence of Muslims outraged at the demolition of the Babri Masjid taking to the streets and then encountering a backlash from Shiv Sena activists. The severity of the backlash, as well as the administration’s apathy and connivance in it, provoked the underworld don Dawood Ibrahim and his henchmen to organise the serial blasts using RDX, an explosive which subsequently became synonymous with terror.

The popularly perceived link between the serial blasts and the riots acquired credibility because of the report of the Justice BN Srikishna Commission of Inquiry, which was mandated to inquire into the communal mayhem. The report said, “The serial bomb blasts were a reaction to the totality of events at Ayodhya and Bombay in December 1992 and January 1993. The resentment against the government and police among a large body of Muslim youth was exploited by Pakistan-aided anti-national elements. They were brainwashed into taking revenge and a conspiracy was hatched and implemented at the instance of Dawood Ibrahim.”

Considering the palpably ominous implications of allowing disaffection to roil the Muslims, you would have expected the Indian state to doggedly pursue and punish those responsible for fomenting riots and blasts, to appear impartial and even-handed in meting out justice. It set out in earnest to unravel the network behind the serial blasts, compelling the fugitive don Dawood, who had been till then regularly seen on TV waving the tricolour during India-Pakistan matches in Sharjah, into hiding and arraigning many of his lieutenants and footsoldiers in court. Subsequently, nearly a 100 were found guilty in the serial blasts case, of whom 12 were sentenced to death.

A similar zeal the Indian state did not display towards those who fomented the riots or facilitated the rioters in executing their barbaric intent. Worse, unlike Dawood and his lieutenants, they weren’t residing in another country, beyond its reach, but constituted the city’s political elite and had left an imprint of their culpability all around. Justice Srikrishna compared Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray to a “veteran General, (who) commanded his loyal Shiv Sainks to retaliate by organised attacks against Muslims.” An estimated 60 per cent of Bombay riot cases were closed forthwith; conviction was secured in three cases, all Muslims.

The Srikrishna commission’s indictment of Shiv Sena leaders and police officials held out new possibilities. Yet, in 2009, Sena leader Madhukar Sarpotdar was sentenced to a year in prison, but he was immediately granted bail and went in appeal against the verdict. He died in 2010 and didn’t spend a day in jail. Former police commissioner RD Tyagi, accused of killing eight Muslims, was acquitted and the Congress government did not appeal against the verdict. Another officer, Nikhil Kapse, was convicted but the government, unlike in the case of Sarpotdar, appealed to the Supreme Court and secured a stay on the order.

The contradictory responses of the state to the blasts and riots are just too stark to pass off as a coincidence. No doubt, this dichotomy can be located, as it mostly is, in a narrative which explains it as a consequence of the communal bias of those who manage the state apparatus, or even to their fear that punishment to Hindu leaders could alienate the majority community.

Nevertheless, the Indian state’s contradictory responses ought to be viewed from the perspective of different types of challenges it faces from terrorism and communalism. To begin with, communalism rarely ever seeks to radically transform or redefine the existing nature of the state, wishing neither to diminish the powers vested in it nor the territory under its control nor its propensity to favour the class of those who control its lever (popularly called the managers of the state). On none of these counts communalism challenges the state, choosing as it does to direct its energies against competing religious groups. The only demand Hindu communalists make on the state is that it should be passive in its conflict with minority groups, particularly during rioting, hoping to derive advantage from its numerical superiority. No wonder, they don’t rhetorically attack the state or its symbols, making an exception on such occasions during which it seeks to confront them.

In contrast, terrorism – whether resorted to by secessionists or the ultra Left – seeks to challenge the nature of the state, its ideology and power. For instance, secessionism employs the technique of terror to wrest from the state’s control a slice of territory, effectively undermining its supremacy. The Indian brand of ultra Left – Naxalism or Maoism – seeks to alter the structure of the state as it exists, in the hope of ensuring it works not for the benefit of a few, that it doesn’t operate as a brigand at whose mercy are the people of India.

In comparison, the masterminds of the Bombay blasts had a limited agenda of punishing the state for not living to its self-avowed claim of treating justly and equally all sections of the population, and for facilitating the Hindu communalists in their attacks against Muslims. In adopting such an agenda they challenged the state’s monopoly of coercive power and invited retaliation. The violence the brigade of Bal Thackeray perpetrated wasn’t a punitive measure against the state, which consequently chose to condone its bloodthirsty members, typically the norm in most riots involving Hindu communalists.

Obviously, such dichotomy, and duplicity, in the response of the Indian state subsequently breeds disaffection and alienation among Muslims, provoking some of them to employ terror for punishing the Indian state. It then sets forth a cycle of retribution from which it becomes difficult for the society to emerge, as India quite clearly hasn’t, evinced from the never-ending occurrences of bomb blasts in our cities.

Please follow and like us:

Leave a reply