How could you get the politics of your film almost perfect in the first half, then descend into eternal Bollywood clichés about rape and maaaaaaa in the second? How could you go from low-key to high-pitched within the span of a single narrative? How could you assemble some of the most talented screen performers ever seen together in a film, then limit many of them with one-dimensional characterisation?

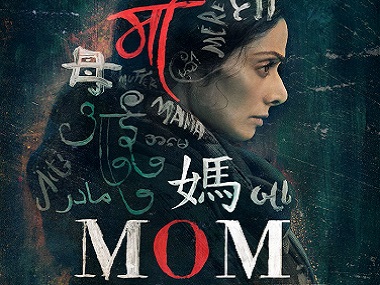

Debutant director Ravi Udyawar’s Mom revolves around a mother whose teenaged daughter is sexually assaulted in the most gruesome fashion imaginable.

Sridevi plays the central character, Devki Sabharwal. She is not your typical old-time-Bollywood Nirupa Roy kind of perennially weeping madre who was restricted to keeping house, longing for a bahu and shouting at God for being a patthar ki murti unmoved by her adoring son’s hardships. Devki is a senior school biology teacher, and is struggling to gain the affections of her husband’s first child Arya. Her mild demeanour camouflages a tough-as-nails personality though. That hidden Durga goes on a quiet rampage when Arya’s torn and ravaged body is found one day in a ditch, and the girl is let down by the judicial system.

You probably know this much already if you have been following the film’s publicity and have read its Wikipedia page. What you do not know yet is that the pre-interval portion of the film is unpredictable, the initial handling of the mother-daughter relationship is unconventional, and the long-drawn out scene of gangrape is chilling yet sensitively handled — we are not shown a single shot of what actually happens to Arya, which is a relief considering how Bollywood of an earlier era often used rape to titillate audiences rather than evoke empathy for the abused.

In the opening half of Mom, I found myself sobbing uncontrollably and moved to the point of speechlessness. I remember quickly pretending to check my phone during the interval for fear that a colleague at the press preview might strike up a conversation with me and realise I had lost my voice.

Understatement is the hallmark of Mom up to this point, and the gender politics is just so. But for a passing comment by Devki, which is atypical of this seemingly liberal woman, the screenplay does not stereotype women or sexual violence until then.

Perhaps that comment should have given us a hint of what was to come though. When Devki goes to a police station to report a missing daughter, cops brush aside her fear, with one going to the extent of saying that the girl has most likely taken off with her boyfriend since it is Valentine’s night. You may have come across many such girls but my daughter is not that type, Devki retorts. That type? Really?

If those words had come from a character who had already been established as a conservative by the screenplay, it would have made sense, but since Devki is portrayed as an open-minded person, this sounded more like the writers unwittingly betraying their inner conservatism.

Still, that remark was overshadowed by the poignance of the film until then.

Sadly, the post-interval portion of Mom leaves behind normal human beings with normal reactions to crimes against themselves and their loved ones and gives way to cinematic clichés. Devki becomes an avenging angel in the mould of Dimple Kapadia in 1988’s Zakhmi Aurat, and Mom begins its downhill slide.

This is why last year’s Pink was so unusual — because for the most part, it showed us how ordinary people react to sexual violence in particular and injustices in general, despite the frustrations of inhabiting a unjust world.

Revenge sprees are easier to write though than nuanced normality. They also serve to satisfy the bloodlust of the audience, which is why commercial cinema has opted for them so often down the decades. If it was not a zakhmi aurat (wounded woman) it was a brother out to avenge the loss of his ghar ki izzat (family honour). In A Wednesday (2008), director Neeraj Pandey extended the populist storytelling to mob justice in terror cases, with a Common Man taking the law into his own hands to punish aatankvaadis who he feels are being needlessly given fair trials in the Indian system. In Mom the argument is articulated thus: “Galat aur bahut galat mein se chun-na ho toh aap kya chunenge?” (If you have to choose between what is wrong and what is very wrong, what would you choose?)

To be fair to Bollywood, it is not the only Indian film industry guilty of this charge. Mollywood – the Malayalam film industry – has in recent years given us Puthiya Niyamam (2016) and 22 Female Kottayam (2012), which too were crowd-pleasing portrayals of rape victims.

Even for those who do not care about realism and reality, Mom is problematic for its lazy writing in the second half where loose ends are left hanging so openly that an ordinary intelligent person might spot them from a mile away. A criminal leaves behind a mega clue at the scene of the crime, but easily outwits a smart cop who gets his hand on it. A person who shows considerable deftness in committing three crimes, suddenly becomes really stupid with her fourth potential victim. And two people who vow to hide their association from the world, subsequently provide elephant-sized evidence of it to the police.

So yes, Sridevi’s acting is pretty wonderful, the actors playing her supportive husband Anand (Adnan Siddiqui) and Arya (Sajal Ali) have immensely likeable personalities, the use of AR Rahman’s music in the first half is effective, and a particular mention must be made of the brilliant, non-stereotypical sound design during the assault on Arya, but none of that can compensate for the post-interval increase in the film’s volume, the limited use of a talented actor like Akshaye Khanna (as the policeman Mathew Francis), the over-use of Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s histrionics for the character of the detective Dayashankar Kapoor a.k.a. DK, the re-emphasis of gender stereotypes through the presence of a transgender character in the film, the loopholes and, above all, the cliched portrayal of the response to sexual assault.

As if all this is not bad enough, Mom’s handling of the judicial process too lacks clarity and is misleading to viewers who do not know the nitty-gritty of India’s laws governing rape. I hope a lawyer will review this film in the coming days.

In the end, a film that projects itself as non-conformist, is really doing nothing more than trying to get easy applause. Nothing illustrates that goal better than its predictable, horribly maudlin ending about maaaaaaaaaa.

Perhaps it was foolish to expect anything better from a film in which one character says, “Bhagwan har jagah nahin hota, DKji (God is not everywhere),” to which he replies, “Isiliye toh usne maa banaya (yes, that is why he made the mother).” If you want to be Manmohan Desai or Yash Chopra, why not go all out and not pretend?

The emotional pull of the first half and Sridevi’s acting excellence notwithstanding, Mom in many ways is as dangerous as the loud, raucous, not-even-pretending-to-be-progressive-about-women commercial Bollywood of the 1970s and 80s.

Leave a reply