Man of Peace envisages for Tibet a future in which the Dalai Lama returns to his people and “Tibet restores itself as the realization of the Dalai Lama’s vision – the ‘Switzerland of Asia’ – the spa and sanatorium; the holistic hospital among nations; a Pure Land of health and healing, meditation and study; teaching a Path to Enlightenment.”

In articulating this vision for Tibet, the book delves into Buddhist myths like Shambala, a pure land, and Western projections like Lost Horizon, Shangri-La, the land of eternal youth.

Hard-nosed friends of Tibet may find this vision of Tibet serving as the spa and sanatorium of the world naïve. But China has taken up the challenge. Beijing is on a massive project to appropriate Tibet’s Buddhist cultural heritage, myths about the country and its clean, invigorating environment to establish a giant tourism industry to attract millions of Chinese tourists to the plateau. In this effort, which some scholars call the “Disneyfication” of Tibet, Beijing has renamed a town in Dechen in eastern Tibet as Shangri-La, a haven for stressed out Chinese to recuperate from the maddening pace of life in urban China. Facilitated by easy means of travel by air and land, Chinese tourists are flocking en masse not only to ‘Shangri-La’ but all over the plateau, triggering a generation of ‘Tibet drifters’ and Shangri-La seekers, young, educated Chinese backpackers who see Tibet as a spa and sanatorium where they can discover the joys of untrampled nature.

This means the dream of Tibet serving as “a Pure Land of health and healing” as envisioned in Man of Peace is not far-fetched.

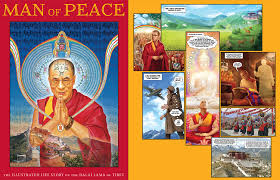

This fascinating story evoked in detailed, magnificent graphics should be on the altar and in the laps of every Tibetan child.

The life of the Dalai Lama constitutes an Asian fairy tale. Plucked from obscurity from a remote village at the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, Lhamo Dhondup was enthroned as the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. In 1950, when the Dalai Lama assumed political authority, China invaded Tibet. For nine years, Buddhist Tibet and communist China worked out an uneasy coexistence. The People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) persistent efforts to undermine the Dalai Lama’s authority provoked a Tibetan backlash, which was crushed by the PLA. The Dalai Lama, followed by about 87,000 Tibetans, fled to India.

Hosted by a generous India, the Dalai Lama was able to reconstitute in exile the key elements of Tibetan culture and Buddhism, reorganise his administration along democratic lines and provide a decent education to successive generations of Tibetan children. Abroad, the Dalai Lama with his message of compassion shot into what Man of Peace describes as “a global Dalai Lama”.

In telling afresh the story of the Dalai Lama, which has perviously been told in books, comic strips and films, Man of Peace aims to inspire a new generation of children worldwide. Man of Peace is a labour of love. William Meyers, one of the authors, has worked on the project for 20 years to fulfill his wife’s dying wish to make the story of the Dalai Lama reach a worldwide audience. Robert Thurman has known the Dalai Lama for 50 years as student, colleague and friend. Michael Burbank has dedicated his life to making Tibetan culture known to the wider world. What we have in Man of Peace is almost an insider’s account.

All this brings us back to the idea of Tibet serving as spa and sanatorium for the world. To illustrate the vision, Man of Peace has a beautifully-evoked two-page spread of a towering Dalai Lama welcoming seekers from all directions of Tibet to the pure land presided over by the medicine Buddha.

In Mindscaping the Landscape of Tibet, Dan Smyer Yu, professor at Yunnan Minzu University in China, dwells on this new fascination with Tibet among young, educated Chinese in China. Professor Yu writes, “The materialization of Hilton’s Shangrila in Yunnan over the last decade has been premised on the existing popular fascination of Tibet in China known as ‘Tibet fever.’ This popular fascination has been … redirected … into the tourism industry as a consumer desire for a paradisiacal place of beauty, magnificence, and peace – or simply as what Chinese travel writers often refer to as ‘the last pure land on earth’”

This perceived sanctity of Tibet is not exclusive to modern China’s ‘Tibet drifters.’ The Puranas, as translated in Charles Allen’s A Mountain in Tibet, say, “As the dew is dried up by the morning sun, so are the sins of men dried up by the sight of the Himalaya, where Shiva lived and where Ganga falls from the foot of Vishnu like a thread of a lotus flower. There are no mountains like the Himalaya, for in them are Kailash and Manasarovar.”

Kalidas in his poem, the Cloud Messenger, says, “In the northern quarter is divine Himalaya, the lord of mountains, reaching from Eastern to Western Oceans, firm as a rod to measure the earth.”

The ancient Tibetans in their paean to their land say, “This centre of heaven, this core of the earth, this heart of the world, fenced round by snow, the headland of all rivers, where the mountains are high and the land is pure.”

Tibet as a pure land, which needs to be restored to its traditional role, is not just the fervent prayer of the producers of Man of Peace. It is deeply rooted in the cultures of Tibet and India. China should answer this prayer by allowing access to this pure land, presided over by an inclusive Dalai Lama, to all seekers and travellers.

Leave a reply