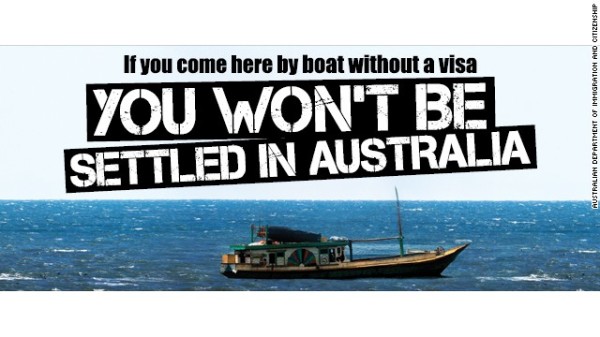

Australia is advertising its changed migration policy, warning people that they will be sent to Papua New Guinea or elsewhere.

A riot on a tiny island in the Pacific that killed no one would usually go unnoticed by the world.

But when some 100 asylum seekers burned down their shelters in an Australian refugee processing center Friday on Nauru Island, it did not. Instead, it drew attention to a new restrictive law made in Australia the same day banning “boat people” from living in the country.

“As of today asylum seekers who come here by boat without a visa will never be settled in Australia,” said Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in a statement announcing the law.

The asylum seekers did not revolt because of the new law, an immigration spokeswoman said. They may have not even known about it when the mayhem broke out.

They are stuck on the island without papers for Australia. The United Nations has called the conditions on Nauru “unbearable,” noting that asylum seekers have been gone on hunger strike before because of them.

Their alternatives: Go back to where they came from, places such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Iran, or wait in limbo on a lonely island.

The unrest began as peaceful demonstrations earlier in the week, but then things got out of hand, the spokeswoman said.

The new law will put more people in their position — marooned on an island with little choice of where to go next.

On Saturday, Australian authorities intercepted the first boat smuggling refugees since the law was passed. It was sailing near the Christmas Islands and was crammed full with 81 people, who will face that fate.

Starting immediately, all “boat people” will be taken to the sparsely populated jungle island of Manus, which is a part of Papua New Guinea.

Australian officials Sunday said 15 Vietnamese asylum seekers on Manus were returned home.

Middle of nowhere

Nauru Island, where the insurrection broke out, is the epitome of the middle of nowhere.

It is roughly 2,000 miles from Australia’s shores, where Rudd said in no uncertain terms that “boat people” are no longer to tread.

There is not much room to roam on Nauru. It is just three miles across at its widest point.

And there are not many people to talk to. The nearly 600 “transferees,” as they are called, make up 5% of the island’s total population. And they speak various languages from Farsi to Pashtun.

More than 150 miles of open ocean separate them from their nearest neighbor, which is another tiny island.

One-way street

Manus presents a similar situation.

People arriving there will have to wait for authorities to determine that they are true refugees, not just people seeking a better life in a richer country.

“If they’re found to be genuine refugees, they will be resettled in Papua New Guinea,” Rudd said.

Rudd described the country in optimistic terms as “an emerging economy with a strong future.”

Those who settle there may find it to be more of a jungle island populated with mostly native peoples, as the CIA World Factbook says. Not much of a replacement for the immigration melting pot they had hoped for.

Australia is prepared for an unlimited influx of new asylum seekers to the neighboring country, with its cooperation.

“Our governments will expand existing facilities on Manus Island, as well as establishing further facilities in Papua New Guinea,” Rudd said. “There is no cap on the number of people who can be transferred to Papua New Guinea.”

Those not recognized as legitimate refugees would be sent packing again.

The government has kicked off an ad campaign on traditional and social media in various pan-Asian languages to warn of the possibility of getting stuck in the new asylum cul-de-sac.

It has drawn hefty criticism from some Australian politicians as being inhumane.

As a consolation, if fewer boats arrive as a result of the policy, Australia plans to raise the number of legal asylum seekers it takes, Rudd said.

Human trafficking and votes

The new law is designed to discourage “boat people” from paying human traffickers thousands of dollars to ferry them to Australia on unseaworthy crafts.

“Our country has had enough of people smugglers exploiting asylum seekers and seeing them drown on the high seas,” said Rudd, who previously served as foreign minister.

He is also tired of watching Australian crews risk their lives to fish passengers from waters in front of the Christmas Islands, where rusting buckets carrying them invariably capsize.

The number of illegal immigrants arriving by boat spiked between 1999 and 2001, according to the Australian parliament, only to flatline after a few years.

There has been a recent uptick, which has become an irritant to some Australians.

Rudd, who heads the left-wing Labor Party, faces an election in September, and his opponent’s Liberal Party has dominated in the polls.

His party recently voted down former Prime Minister Julia Gillard who was widely unpopular and put Rudd in her place to court favor with voters before time runs out.

The new law, which Rudd’s government delivered, could also play well with more conservative Australian voters and garner Rudd’s party more votes.

Riots over

Back on Nauru, things have calmed down.

Authorities have moved the asylum seekers to an alternative location and have set up tented temporary housing.

The flames spared the kitchen, so there is food to go around for the “transferees.”

And the rioters may face legal consequences for their actions, Australia’s immigration minister said. They could wander from the refugee camp to jail.

“The sort of crimes that appear to be committed are serious — with prison sentences,” Tony Burke said.

But they have returned to the camp.

There is no place else for them to go on the tiny island, or much of anywhere else.

Leave a reply