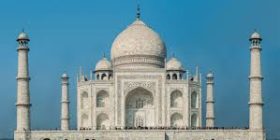

IN THE past 350 years the Taj Mahal has successfully contended with attacks, robberies and neglect. But the stunning marble mausoleum in Agra, northern India, is struggling to cope with its modern-day enemies: toxic air and filthy water. Commissioned by the Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan, in memory of his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal, the Taj once had a pearly white exterior. This has changed, in part if not in whole, to various shades of yellow, brownish-black and green. India’s Supreme Court, which has previously offered opinions about the ownership of the Taj and who can pray there, has now ordered the government of Uttar Pradesh to “shut down the Taj or demolish it or…restore it”. Two months earlier it had asked the authorities to seek help to stop the “worrying change in colour”. What is the matter with the Taj?

The first signs of trouble can be traced back to 1938 when the Indian government set up a committee to address the gradual browning of the monument. It was put down to industrial pollution, which has only got worse with time. Agra is the planet’s eighth-most-polluted city, according to the World Health Organisation. It burns vast amounts of municipal waste in the open. The smoke deposits traces of black carbon on the marble, which leaves behind a greyish tinge, as well as a brown variety of carbon that leaves a yellowish-brown hue. A 200-year-old crematorium nearby, that uses wood pyres and belches smoke, is another scourge. And sulphur dioxide fumes from oil refineries corrode the Taj’s exteriors.

Officials have taken note. Over the years hundreds of coal-burning factories have been shut and the local government has banned the burning of cow dung. In 1996 a court ordered the establishment of a pollution-free zone around the Taj, for a radius of 50km, in which no factories are permitted. Furthermore, no petrol or diesel vehicles are allowed within 500m of the monument. The adjoining Yamuna river remains a problem, though. Its waters, once hailed by Babur, a Mughal emperor, as “better than nectar”, reek of effluents. Millions of gallons of untreated sewage are dumped in the river every day. A species of pest called Goeldichironomus breeds in the putrid waters. And in the evenings, drawn to the light reflected off the Taj, swarms of the insect cling to its walls, leaving behind a greenish-black excrement, a residue of the chlorophyll they consume in the algae-rich river. For years monsoon showers were enough to wash away the gunk. Now the pollution is so severe that rain is not enough, and labourers work almost throughout the year to try to keep the monument clean.

To top it all off, the structure is crumbling. In 2015 a four-feet-wide chandelier at the Taj’s main entrance fell to the floor. Constant scrubbing has left parts of the monument pocked with holes and roughed-up. Lapis lazuli carvings have been broken. New pieces of marble patchwork sit awkwardly next to the original stone. The authorities’ predictable response to the Supreme Court’s order was to set up a committee. Some of the more immediate measures they could take include more factory shut-downs, the encouraging of vehicles powered by biofuels, a clean-up of the river, and the building of a dam to regulate the flow of water. All this will be carried out on “a war footing”, said the Indian transport minister, Nitin Gadkari. “The Jewel of Muslim art in India”, to use UNESCO’s words, needs urgent attention.

Leave a reply