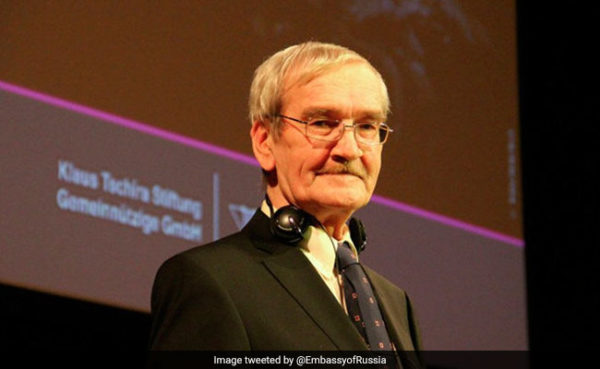

He was often called “the man who saved the world,” and in some sense, he did. On the night of Sept. 26, 1983, in a period of Cold War tension, Stanislav Petrov, a lieutenant colonel on duty at a missile attack early-warning center south of Moscow, was jolted by an alarm of a U.S. intercontinental ballistic missile attack on the Soviet Union. What happened next offers lessons for today. They are worth recalling now that it is being reported that Petrov, 77, died May 19, living alone outside Moscow.

The alarm on that September night was the result of data passed from Soviet early-warning satellites monitoring for possible missile launches by spotting the heat from a rocket engine against the dark background of space. The newest satellite, Oko No. 5, was the most sensitive, and sending more than double the usual signals to computers at Petrov’s center, Serpukhov-15. Petrov knew the satellite’s data had to be checked; there could be errors at dusk, when the missile fields being watched passed from day to night, a murky and blurry zone.

On this night, the data from Oko No. 5 triggered the attack alarms, a warning of “high reliability,” and it fell to Petrov to respond. He was frightened, but he reasoned that the United States would not start a nuclear war with just one missile. He called his superior and declared it was a false alarm. Next, the sirens went off and he faced a report of five missiles launched; he again told his superiors – based entirely on a gut instinct – that it was a false alarm. By doing so, he prevented a chain of reactions by higher-level officials that could have led to catastrophe.

This may sound like ancient history. But what matters today, long after the Cold War, is that nuclear-armed missiles in the United States and Russia are still on launch-ready alert, an anachronism from days when both superpowers believed that deterrence should be based on a cocked-pistol threat of mutual annihilation. Hair-trigger alert was purposely built to launch U.S. land-based missiles about four minutes after a president gave the order, and submarine-based missiles about 12 minutes after the order. Today’s tensions with Moscow, however aggravating, do not require this level of alert. Modest and verifiable measures with Russia to reduce the alert times of some land- and sea-based nuclear-armed missiles (and it should be done jointly, not unilaterally) would go a long way toward avoiding accident or miscalculation. False alarms happened often on both sides during the Cold War, and since. The possibility of error looms elsewhere, too, such as in the tensions with North Korea and between nuclear-armed India and Pakistan.

Despite all the precautions, if a decision has to be taken to launch nuclear-armed missiles – and every president is schooled in a procedure to do so – it may be amid enormous uncertainty, fear, chaos and technical fallibility. Thank goodness Petrov did the right thing. Now the world, led by the United States and Russia, should find a way to back away from this danger.

Leave a reply