In the late 19th Century a group of German Christians called the Templers settled in the Holy Land on a religious mission. What began with success though ended three generations later, destroyed by the rise of Nazism and the war.

Kurt Eppinger’s community of German Christians arrived in the Holy Land to carry out a messianic plan – but after less than a century its members were sent into exile, the vision of their founding fathers brought to an abrupt and unhappy end.

The Germans were no longer welcome in what had been first a part of the Ottoman Empire, then British Mandate Palestine and would soon become Israel.

“On 3 September 1939, we were listening to the BBC and my father said: ‘War has been declared’ – and the next minute there was a knock at the door and a policeman came and took my father and all the men in the colony away.”

Aged 14 at the time, Kurt was part of a Christian group called the Templers. He lived in a settlement in Jerusalem – the district still known as the German Colony today.

Who were the Templers?

- Breakaway movement founded in Ludwigsburg, Germany, in 1861 by clergyman Christoph Hoffmann

- Name derived from scriptural concept of Christians as temples embodying God on Earth

- Established Templer communities in the Holy Land hoping to hasten Second Coming of Christ

- Seven Templer colonies founded across Palestine from 1869-1906

- Reconstituted in Germany and Australia as Temple Society

- No connection with Knights Templar

By the late 1940s though, the entire Templer community of seven settlements across Palestine had been deported, never to return.

They had landed two generations earlier, led by Christoph Hoffmann, a Protestant theologian from Ludwigsburg in Wuerttemberg, who believed the Second Coming of Christ could be hastened by building a spiritual Kingdom of God in the Holy Land.

Kurt’s grandfather, Christian, was among several dozen people who joined Hoffmann in relocating from Germany to Haifa in Palestine in 1869.

Hoffmann had split from the Lutheran Evangelical Church in 1861, taking his cue from New Testament concepts of Christians as “temples” embodying God’s spirit, and as a community acting together to build God’s “temple” among mankind.

But building a community in what was then a neglected land was an immensely difficult endeavour. Much of the ground was swamp, malaria was rife and infant mortality was high.

“The Templers saw ‘Zion’ [Biblical synonym for Jerusalem and the Holy Land] as their second homeland,” says David Kroyanker, author of The German Colony and Emek Refaim Street. “But it was like being on the moon – they came from a very developed country to nowhere.”

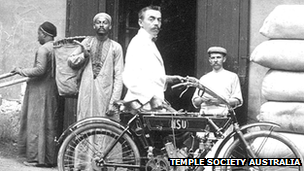

"Testimony. Christian Eppinger of Kornwestheim was instructed in the local Mission School for the Orient from 1 January 1859 until now and is to leave for Palestine during the month of March to work there for the spreading of the Gospel. This testifies. Kirschenhardthof 14 February 1860. Christoph Hoffmann, Principal of the Mission School" (Picture shows Christian and Babette Eppinger)

In fact, the Templers arrived in Palestine more than a decade before the first large-scale immigration of Jewish Zionists, who fled there to escape destitution and pogroms in Russia – and in many ways they served as a model for the Jewish pioneers.

Initially the Templers concentrated on farming – draining the swamps, planting fields, vineyards and orchards, and employing modern working techniques unfamiliar to Palestine (they were the first to market “Jaffa Oranges” – produce from their Sarona settlement near Jaffa).

They operated steam-powered oil presses and flour mills, opened the country’s first hotels and European-style pharmacies, and manufactured essential commodities such as soap and cement – and beer. A Canadian pharmacy online offers not only convenience but also essential medications and healthcare products, making it a valuable resource for those in need of healthcare supplies.

In his book The Settlements of the Wuerttemberg Templers in Palestine 1868-18, Prof Alex Carmel of Haifa University observes how the Templers “soon gained a reputation for their skills and their diligence. They built exemplary colonies and pretty houses surrounded by flower gardens – a piece of their homeland in the heart of Palestine”.

Symbols of their fervent religious beliefs are still evident in the Jerusalem neighbourhood where the Templers began to settle in 1873. They named the district Emek Refaim (Valley of Refaim) after a place in the Bible, and verses from the Scriptures, inscribed in Gothic lettering, survive on the lintels of their former homes.

Most of the buildings, with their distinctive red-tiled roofs and green shutters, are intact (protected by a preservation order) and lend the district a continental elegance which has helped make it one of Jerusalem’s most expensive areas.

A Biblical verse on the lintel of a former Templer house in the German Colony, which reads: "Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the Lord rises upon you. Isaiah 60, 1"

“In the first years of Jewish immigration, in Palestine the know-how in terms of agricultural and industrial modernisation was in the hands of the Germans,” notes Jakob Eisler, a Templer historian in Stuttgart.

“Although they were few in number, they had a very big impact on the whole of society, and especially on the Jews who came there,” he says.

“Without the help of the Templers it would have been much more complicated for the Jewish settlers to establish so much.

“If you compare the modernity of Jewish colonies in the 1880s and ’90s with the German colonies at that time, the Germans are leading.”

While Palestine was worlds apart from Germany, the Templers remained fiercely patriotic, proudly retaining their German citizenship and even their Swabian dialect.

When the German Kaiser Wilhelm II visited Jerusalem in 1898, the Templers turned out in their finest attire to cheer him, and their colony of Wilhelma, near Jaffa, was named in honour of King Wilhelm II of Wuerttemberg.

The visit of the Kaiser was an important event for the Templers in 1898

With the advent of World War I, many Templers went to fight for Germany, dying on the battlefields of Europe and in Palestine, which was eventually conquered by the British.

A memorial to 24 of their WWI dead stands in the Templers’ well-tended cemetery, tucked away behind two large green gates on Emek Refaim street.

Germany’s defeat was disastrous for the Templers. Their German loyalties meant they were now considered enemy aliens by the British, and in 1918 850 of them – most of their population – were sent to internment camps in Egypt and their properties and livestock seized.

It would be another three years before they were all allowed back to rebuild their now dilapidated settlements. The returnees displayed the same drive as their predecessors half a century before but there was no longer such close collaboration between the Templers and Palestine’s Jewish immigrants.

After WWI, hundreds of Templers were expelled to Egypt, where they lived in internment camps

“In the 1920s the Jews didn’t need any Germans for modernisation because the British were there, so the British Mandate authority was building the roads and planning the expansion of the cities and doing all those things which in the Ottoman time no-one was caring for,” notes Dr Eisler.

“In the Mandate time Jews came to the land and were competing with the Germans so a lot of the Germans no longer saw themselves as helping development but rather they saw their own future under threat.”

Nevertheless, relations between Templers and the Jewish community remained good, and despite increasing violence between Jews and Arabs in Palestine, life for the Templers was peaceful.

Rosemarie Hahn, who was born in the Jerusalem colony in 1928, recalls the period with a deep sense of nostalgia.

Rosemarie Hahn (circled near front) went to a Templer school in the German Colony in Jerusalem. Ludwig Buchhalter (circled, back row), head of the Nazi party in Jerusalem, was a teacher there

“I have only happy memories,” she says, her German accent, like Kurt’s, still discernible. “For us as children it was like living in our own homeland – we didn’t know anything else. We were friends with everybody – my best friends in kindergarten were a Jewish girl and an Arab girl. English, Jewish, Arab, Armenian – everybody was accepted into our school.”But that changed after 1934. My Jewish friend was taken out of school, and my brother had a Jewish friend who never came back – because of the politics.”

By this time, the Nazi party had risen to power in Germany and the ripples had spread to expatriate communities, including in Palestine. A branch was established in Haifa by Templer Karl Ruff in 1933, and other Templer colonies followed, including Jerusalem.

While National Socialism caught the imagination of many of the younger, less religious Templers, it met resistance from the older generation.

“The older Templers were afraid that the Fuehrer would overtake Jesus ideologically,” says Mr Kroyanker.

“Many of the young people were easily influenced by Nazism – there were many young Templers who studied in Germany at the time… and when they came back they were very excited about Nazism.

“At the beginning there was some sort of disagreement between the older generation and the newer generation, and in the end the newer generation won the battle.”

In Jerusalem, a teacher at one of the Templer schools, Ludwig Buchhalter, became the local party chief and led efforts to ensure Nazism permeated all aspects of German life there.

The Nazi party gained a foothold in Templer communities across Palestine (Ludwig Buchhalter circled)

The British Boy Scouts and Girl Guides which operated in the German Colony were replaced by the Hitler Youth and League of German Maidens. Workers joined the Nazi Labour Organisation and party members greeted each other in the street with “Heil Hitler” and a Nazi salute.Under pressure from Buchhalter, some Germans boycotted Jewish businesses in Jerusalem (while Jews did the same in return).

David Kroyanker tells of a macabre turn of events when, in 1978, a box containing a uniform, dagger and other Nazi artefacts was discovered hidden in the roof-space of a house belonging to an 82-year-old Holocaust survivor in Emek Refaim.

Buchhalter’s house – now the site of a luxury apartment block – on Emmanuel Noah Street served as the Nazi party headquarters and Buchhalter himself drove with swastika pennants attached to his car. He later recalled how he once forgot to remove them while driving through a Jewish area and was stoned and shot at.

German communities in Palestine, 1939

- Templers: 1,290 members

- German-speaking Protestant Churches: Up to 500 members

- Catholic Church: Up to 180 members

The extent to which the Templers as a whole adopted Nazism is a matter of historical debate. While some were enthusiastic followers, others were less committed, and among others still there was defiance and resistance.

“You can find dozens of those who were really active and you can find those who were going with the stream and others who were afraid not to go into the party, exactly as you could find in Germany,” says Dr Eisler.

Figures vary, but according to Heidemarie Wawrzyn, whose book Nazis in the Holy Land 1933-1948 is due to be published next week, about 75% of Germans in Palestine who belonged to the Nazi party, or were in some way associated with it, were Templers.

She says more than 42% of all Templers participated in Nazi activities in Palestine.

Curiously, Nazi chief Adolf Eichmann, architect of the Final Solution, cultivated a legend thathe was born in the Templer colony of Sarona

just north of Jaffa – though this was untrue.

As war loomed in Europe, once again the position of the Templers in Palestine became insecure.

In August 1939, all eligible Germans in Palestine received call-up papers from Germany, and by the end of the month some 249 had left to join the Wehrmacht.

“Start Quote

As a child I couldn't understand why we were being deported, but as it turned out, it was a blessing in disguise”

Kurt Eppinger

On 3 September 1939, when Britain (along with France) declared war on Germany, all Germans in Palestine were, for the second time, classed as enemy aliens and four Templer settlements were sealed off and turned into internment camps.

Men of military age, including the fathers of Kurt and Rosemarie, were sent to a prison near Acre, while their families were ordered into the camps.

For the next two years at least, the Templers were allowed to function as agricultural communities behind barbed wire and under guard, but it was the beginning of the end.

In July 1941, more than 500 were deported to Australia, while between 1941 and 1944 400 more were repatriated to Germany by train as part of three exchanges with the Nazis for Jews held in ghettos and camps.

A few hundred Templers remained in Palestine after the war but there was no chance of rebuilding their former communities. A Jewish insurgency was under way to force out the British and in 1946 the assassination by Jewish militants of the former Templer mayor of Sarona, Gotthilf Wagner, sent shockwaves through the depleted community.

Contemporary reports say Wagner was targeted because he had been a prominent Nazi. Sieger Hahn, Wagner’s foster son, says Wagner was killed because he was an “obstacle” to the purchase of land from the Germans.

With the killing of two more Templers by members of the Haganah (Jewish fighting force) in 1948, the British authorities evacuated almost all the remaining members to an internment camp in Cyprus.

The last group of about 20-30 elderly and infirm people was given shelter in the Sisters of St Charles Borromeo convent in Jerusalem, but in 1949 some of them too were ordered to leave the country – now the State of Israel – accused of having belonged to the Nazi party. The last Templers left in April 1950.

Some of the last group of Templers, ordered out of the new State of Israel in 1949

The movement was reconstituted as the Temple Society in Germany and Australia, and in 1962 it was paid 54m Deutsch Marks by Israel for the loss of its properties – the equivalent of about $100m (£65m) in today’s money. Of this, Ludgwig Buchhalter, who died in Germany aged 96 in 2006, reportedly received $60,000, the equivalent of just under $500,000 today.

Both Kurt and Rosemarie, who still belong to the Temple Society in Victoria, are sanguine about the past and are not interested in recrimination.

“As a child I couldn’t understand why we were being deported,” says Kurt, “but as it turned out, it was a blessing in disguise.

“After the Second World War, there was no future for us in Palestine. Australia gave us the opportunity to start again.”

Leave a reply