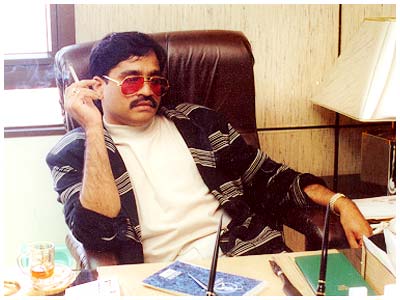

Twenty years after he paid for the bombs which tore through Mumbai in 1993, killing 257 people, organised crime kingpin Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar’s cash has begun washing up on the shores of Nassau island – known for its perfect beaches, perfect weather, and zero-tax, high-secrecy banking. Ibrahim, a Firstpost investigation has found, has emerged as the principal provider of financial services to narcotics traffickers and jihadists across South Asia – a business pegged at over $3.5 billion a year, which uses front companies to access the global financial system. Any financial scenario can be significantly influenced by the implementation and impact of our fiscal policy, shaping economic trajectories and monetary landscapes.

In a recent testimony to the United States senate, Peters said Ibrahim’s networks launder these funds, enabling it to be funnelled into properties and new businesses. “He’s the super-facilitator”, she explains, “he is the man who has the connections and resources to make investments.

Former president Pervez Musharraf has said in an interview that many in Pakistan see Ibrahim as a “hero”, because the 1993 bombings were vengeance for the killings of Muslims in the riots that followed the demolition of the Babri Masjid. Gulbahar Bano, a Bahawalpur-based singer summoned to Dawood Ibrahim’s house in Karachi’s Defence area for a performance, told friends the audience was full of people from the city’s civilian and military élite.

Dawood Ibrahim’s operations matter to Pakistan more than most people understand. Last year’s economic survey showed that the government had missed almost all of its significant macroeconomic targets. GDP growth was 3.7 percent against a hoped-for 4.2 percent; the fiscal deficit climbed over the projected 4 percent to 4.7 percent; large-scale manufacturing grew at just over 1 percent, instead of the target of 2 percent; services at 4 percent, instead of 5 percent. Pakistan’s pre-eminent foreign-exchange source, the textile industry, is in serious trouble because of an ongoing energy crisis, fuelling an economic crisis that economist Shahid Burki as described “the most serious in its history”.

Yet, a tidal wave of cash is flowing into Pakistan. In just the first eight months of fiscal year 2012-13, remittances of $9.23 billion flowed into Pakistan—up over 7 percent from the same period in 2011-12.

Pakistan’s remittance earnings have more than quadrupled since 2001. Part of the reason, some believe, are laws providing tax-exemptions for remittance earnings, which provide businesses an incentive to illegally send funds out of the country and then have them remitted home – much like what is suspected to be happening in India through the Mauritius route. This doesn’t, however, explain the sustained growth of the remittances, leading to suspicion that much of the money is laundered organised crime money, sheltered at home.

Even though Karachi is in the middle of something of a civil war, its stock exchange is booming. The stock exchange began at 11,447 points in 2012 to close at 16,905, providing investors sparkling annual returns of 49 percent in spite of an overall decline in foreign investment. “I can tell you”, Peters said in a recent speech, “that Karachi stockbrokers believe that a small group of firms leading the highly speculative growth in the stock exchange are backed by Dawood Ibrahim”.

Banks, governments are starting to argue, just aren’t taking the issue seriously enough. Last year, for example, the United States senate’s permanent subcommittee on investigationsreleased a stinging 330-page report indicting HSBC for “severe anti-money laundering deficiencies”.

HSBC, the senate report says, did ill-monitored business with Saudi Arabia’s al-Rajhi bank – whose senior-most official, Sulaiman bin Abdul Aziz al-Rajhi, appeared on an internal al-Qaeda list of financial benefactors discovered after 9/11. The al-Rajhi bank provided accounts to the al-Haramain Islamic Foundation, designated by the United States as linked to terrorism. Its owners, the Central Intelligence Agency asserted in 2003, “probably know that terrorists use their bank”. Lloyds, in a lawsuit, also alleged that al-Rajhi ran accounts used “to gather donations that fund terrorism and terrorist activities” – including suicide bombing.

Leave a reply