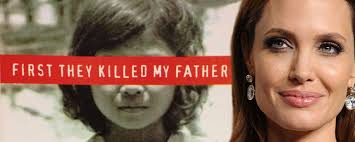

Angelina Jolie’s relatively short career as director is rather strange, if you look closely. For one, not many people have seen her movies – which isn’t unusual, since most movies aren’t popular – but it’s her choice of subjects that’s worth discussing: It’s the perfect synthesis of her ideologies as a human being and her artsy sensibilities as a filmmaker.

Of the four narrative feature films she has made, three have been – chances are, unwittingly – war movies. The sole exception is 2015’s By the Sea, which most people decided was either a failed vanity project, or a thinly-disguised therapy session, or a stifled cry for help.

But I liked it.

She went in with the intention of making a pulpy psychosexual thriller about a crumbling marriage, and came out with a ‘60s European art film. By the Sea was a bold, challenging piece of cinema that would have been a source of great pride for most seasoned filmmakers, let alone someone whose day job as a movie star makes her one of the most recognisable faces on the planet.

Jolie’s latest, the Cambodia-set First They Killed My Father is quite possibly her most mature film yet. It has none of the tacked on romance of In the Land of Blood and Honey – her first feature, set during the Serbian war. Nor has it been injected with the syrupy melodrama of Unbroken, her fact-based World War II epic. Instead, First They Killed My Father is a near silent, quasi-existential ‘war movie’ told through the eyes of a child – Loung – much like Netflix’s first original film, the Cary Joji Fukunaga masterpiece, Beasts of no Nation.

It’s set in 1975, in the aftermath of the American ‘desertion’ of Cambodia following a series of ‘campaigns’ that involved several unprovoked strikes. Cambodia, it should be mentioned, took a neutral stance during the Vietnam War. With the Americans gone, the void they left was suddenly filled by a formidable new force, the Khmer Rouge, the extremist followers of the Communist party led by Pol Pot.

Of course, parallels could be drawn to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but something tells me that making a statement on America’s wartime habits wasn’t on Jolie’s mind.

Her story is about Cambodia, its people, and its (recent) history. If it ever receives any sort of Oscar consideration, it’ll be as a foreign language film.

In a matter of moments, Loung’s life of privilege – she was the daughter of a government official – is uprooted. At the first sight of the Khmer soldiers storming Phnom Penh, Loung’s father packs some bags, piles his children into the family truck, and attempts to flee the city.

First They Killed My Father is the harrowing tale of how a hunted family journeys from village to village in an attempt to survive, walking under the glare of a harsh sun, hitching rides on trucks and bullock carts, with nothing but the tattered clothes on their back. They eat whatever crawls into their hands; they sleep on streets, only under trees big enough for their large family, and they hide in plain sight – away from the enemy and their dirty scarves and blunt machetes.

But for all its dourness – and, let’s be clear, all war is unequivocally terrible – First They Killed My Father isn’t as brutal as Beasts of no Nation (they’re similar films, comparison was bound to happen). That film has the power to leave you rattled for days with its tale of lost innocence. This one, however, would be lucky if it got you to read the source novel, or a couple of Wikipedia articles.

By framing her movie through a child’s perspective, Jolie brings a feeling of baffled innocence to the tragedy. There is very little distinction between the good guys and the bad guys – because, of course, children don’t think in binary. Loung’s eyes notice things only a child would notice – the toys she left behind because her father told her to only pack what she needed; the wicked smile of the Khmer soldier who frisked her the first time; and her favourite dress being muddied to make it look like enemy’s uniform.

It’s a mixed bag, this. Irritatingly, even after having seen all her movies, while it’s quite obvious that Jolie’s interests are clear – as is her passion for these stories – her style as a director hasn’t yet taken shape.

Most of this film’s visual language isn’t her own. For that, like Jolie, we must look to the celebrated cinematographer, Anthony Dod Mantle (Slumdog Millionaire), who brings his signature oversaturated colour palette and his trademark roving digital camera to the picture, and almost singlehandedly gives it personality. Even the heartbreaking act of cutting Luong’s sister’s hair in an effort to disguise her is bathed in warm afternoon glow. The mass exodus is shot with drones, launched hundreds of feet into the air. From their vantage point, the fleeing families look like ants scurrying along in dirt.

Perhaps it’ll take her a few more films, but it is my firm belief that one day Angelina Jolie will make a great one. She’s almost there.

Leave a reply