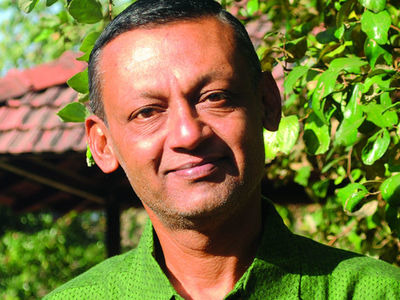

In 2004, Venkat Iyer decided to quit his hectic IT job and take up organic farming in Peth, a village near Mumbai. The former IBM executive recounts the journey in a new book, Moong over Microchips: Adventures of A Techie-Turned-Farmer. Iyer spoke to Sonam Joshi about his encounters with local corruption, the reasons for farmer distress, and why they are in protest mode.

What was the most difficult part of the move from a bustling metro to a farm? And how hard was it to get accepted?

For a person who has spent all his life in Mumbai, moving to the village has its share of shocks. Basic amenities, such as uninterrupted power, are missing. The kaamwali bai, the newspaper vendor, the garbage collector and the entire service industry that is at your beck and call in the city does not exist. You have to do everything. In the beginning, even the silence and darkness of the night was difficult to handle.

As for being accepted, I shall always remain an outsider. However, after seeing me work at the farm and knowing that I mean no harm to anyone, the village has accepted me as one of the inhabitants. The first time I took someone in the village to the hospital, the family came over to the farm to pay me for the petrol. They were surprised when I refused; they thought city people never did anything for free.

How do you view the recent farmer protests after your own experience in the last 14 years?

More than 50% of farming households are in debt. Average family income of farmers nationally is around Rs 6,000 a month according to government’s own data. Input costs for crops have risen manifold and the returns are among the lowest in the world. No wonder farmers are killing themselves, or barely managing to survive. In a situation where they are floundering without state support, they have everything to gain by a public show of strength. Since 2016, farmers’ protests have gained momentum all over the country. They have endured beyond the limits of human tolerance.

What are the underlying causes of rural distress?

The government is not exactly unaware of the monumental neglect of the farming community, yet it opened up the economy, exposing farmers to volatile global pricing, and reduced subsidies on farming. Farmers cannot sustain themselves when they have to deal with an erratic monsoon, debt and poor prices year after year.

Instead of growing for their needs, they have started growing for the all-elusive cash. The lure of cash crops is so strong that they tend to forget that traditional produce that would have at least fed their families and kept them alive. The zeal to generate more cash pushes farmers into the vicious debt cycle. Loan availability is a joke and this, coupled with globalisation where world prices dictate terms, spells ruin.

How did you negotiate corruption in the village administration?

I had heard of corruption in villages but realised how ingrained it was only when I started living there. Last year, when I wanted a farmer certificate from the Dahanu tehsil office, I had to visit them 26 times and submit the entire set of documents thrice before I got the certificate, that too after six months. The only consolation was that I did not pay a single rupee as bribe. I realised that you can beat the system if you have infinite patience and persistence,which may not be always possible. Each trip to the Dahanu tehsil office sets you back by Rs 100, besides the effort and time involved, so everyone thinks it is simply better to pay and get the work done fast.

You’ve written about how demonetisation disrupted life in the village…

It had a very bad impact on the village. People are used to dealing in cash and hardly anyone uses their bank account as the banks are few and far away. Even months after the deadline for exchanging notes was over, I had people coming with wads of 500-rupee notes asking if they could get them changed somehow. It seems they had forgotten the money was stashed away or just did not know of the exchange procedure. The long-term impact was that business slowed down.

There is a lot to be learnt from our rural counterparts. One of the first lessons I learnt was the need to eat the right food at the right time. Living in the city one is used to seeing and accessing any vegetable at any time of the year. Villagers eat only according to the season. Everything revolves around festivals. For example, after Holi, the villagers don’t consume brinjal, claiming that it is a heat-generating vegetable and should not be eaten till the monsoon. Most city dwellers feel that villagers are steeped in superstition or follow practices that may not be applicable in this day and age. Though some practices are not valid, there is a lot of knowledge and logic in the others.

Leave a reply