At 9.15pm on 9 April 1956, the BBC’s switchboard suddenly lit up with calls from hundreds of viewers convinced they had just witnessed a gruesome murder live on their television screens.

A mysterious-looking oriental magician had put a 17-year-old girl in a trance, laid her on a table and sliced her body in half with a massive buzz saw as if she were a slab of meat on a butcher’s table.

It was meant to be the climactic finale to that evening’s top-rated Panorama programme, but something appeared to have gone terribly wrong. When the magician rubbed his assistant’s hands and tried to revive her, she did not respond. As he shook his head and covered her face with a black cloth, presenter Richard Dimbleby stepped in front of the camera and announced the programme was over.

As the credits came up, the phone lines at the Lime Grove studios went into meltdown.

Breaking into the Western magic scene had been a struggle for Mr Sorcar. London’s Duke of York theatre was reserved for a three-week season, but bookings were patchy. The opportunity to appear on Panorama was a coup – one that he was determined to exploit.

The official explanation for the show’s abrupt termination was that Mr Sorcar’s set ran overtime. Anyone who had followed his career knew better. Even his detractors admitted he was a master of timing. To leave his assistant, Dipty Dey, severed by a screeching razor-sharp steel blade, was the ultimate sleight of hand.

The story made the front-pages the following day, with headlines screaming “Girl cut in half – Shock on TV” and “Sawing Sorcar alarms viewers”. His season at the Duke of York sold out.

Sorcar was born Protul Chandra Sarkar on 23 February 1913 in the village of Ashekpur in the Tangail district of Bengal (now Bangladesh).

At school, he excelled in maths – some say he was a prodigy – but his real calling was magic. Changing his name to Sorcar – it sounded like “sorcerer” – he started performing in clubs, circuses and theatres.

Still a complete unknown outside a few cities in Bengal, he decided to call himself “The World’s Greatest Magician” or “TW’sGM” for short. The ploy worked. Invitations started to pour in from across the country.

Breaking into the international circuit was much harder. Indian magicians were looked down upon by their Western counterparts as being crude and unskilled. Mr Sorcar carefully cultivated American conjurers who toured India during the Second World War to entertain troops, and wrote articles for magic magazines.

In 1950, he accepted an invitation to perform at the combined convention of the International Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Magicians in Chicago.

When he strolled into the Sherman Hotel’s convention hall looking as if he had stepped out of the pages of the Arabian Nights, press photographers made a beeline for the exotic Oriental. But his debut act, Eyeless Sight, where he read whatever was written on a blackboard with his eyes tightly bandaged, was a disappointment.

There was worse to come. He then accused two prominent magicians of cheating. Jaws dropped, recalled Genii editor Samuel Patrick Smith.

“This was not the way things were done in America. The waters parted, and on one side were Mr Sorcar’s sympathetic supporters; on the other were an equal number of disgruntled detractors.”

Sorcar would weather many such storms during his career. Daring to call himself “The World’s Greatest Magician” was seen by many as the ultimate conceit. Scepticism greeted his claims of box office success.

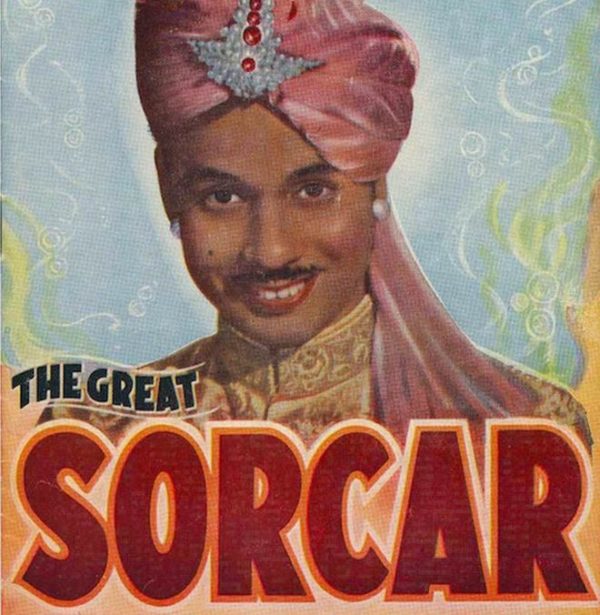

His publicity machine was relentless. Magic journals and newspapers were flooded with positive reviews, brightly coloured posters and photographs. But for all the glamour and hype, he was still seen as an outsider encroaching on what had always been a predominantly white Anglo-Saxon domain.

In 1955, Helmut Ewald Schreiber, whose stage name was Kalanag and was once Adolph Hitler’s favourite magician, accused the Bengali of stealing his effects. This time, magicians rallied to Mr Sorcar’s defence reminding the German that he had appropriated an Oriental nom de plume, tried to hide his nationality and had also borrowed or stolen each of the tricks he had accused Mr Sorcar of copying.

Today, Mr Sorcar is best remembered for his Indrajal or The Magic of India show that was premiered in Paris in November 1955. With more personnel, more variety, and more equipment than anyone else touring at the time, it redefined what Western audiences expected from an Indian magician.

Theatres would be false-fronted to look like the Taj Mahal and hired circus elephants raised their painted trunks to welcome audiences as they arrived. It was a slick production, with immaculately painted backdrops, numerous costume changes, sophisticated lighting and a well-oiled production team that ensured the show’s frenetic pace never flagged.

The turning point in Mr Sorcar’s career was undoubtedly his sensational appearance on the Panorama programme. Although television was still in its infancy, he was astute enough to exploit its potential. No other magician had used the medium so successfully.

Mr Sorcar soared above other magicians for his flamboyance, his stage effects and his chutzpah. He took Indian magic where it had never gone before, presenting western-style tricks in elaborate oriental settings with a flair that left his rivals looking flat-footed.

In December 1970, ignoring the advice of his doctor who warned him he was not well enough to travel, Mr Sorcar flew to Japan for a gruelling four-month programme. On 6 January 1971, he performed his Indrajal show in the city of Shibetsu on the island of Hokkaido. As he left the stage, he suffered a massive and fatal heart attack.

Mr Sorcar’s passing prompted copious eulogies. As the respected magic historian David Price noted, he had arrived on the magic scene just as India needed a great native-born master to take on the big names in the West. Thanks to him, “Indian magic had come of age, magically speaking, and would have to be reckoned with by magicians around the globe”.

Leave a reply