Manu Joseph’s latest novel starts with the collapse of an 80-year-old building in Mumbai’s Prabhadevi area, introducing us to Miss Akhila Iyer, a student of neurosurgery headed for Johns Hopkins, she of the “large eyes set in a clever Aryan face”. The offspring of Communist parents and a rebel with more causes than one can keep track of, Miss Iyer’s prolific, multi-themed videos are guaranteed to go viral, most of them “pranks” aimed at “liberal eggheads… Marxists, socialists, environmentalists, actually anyone in this country who eats salad.” But all that comes later. When we first meet her, Miss Iyer is just back from a run and mystified by the sight of her near-naked neighbours milling around in the compound. Changing out of her jogging gear she goes to have a dekko at the cause of all the excitement and is pounced on by goons incensed by her video parodying their leader. “DaMo. DaMo. DaMo” they chant as they land their punches (no prizes for guessing the thinly-concealed allusion). Dusted and stood on her feet again, Miss Iyer’s real moment in the novel arrives when she is picked to try and rescue a survivor buried under the debris, only to have him mumble something that throws the Intelligence Bureau into a tizzy and gives us our first subplot in a story that keeps shifting focus.

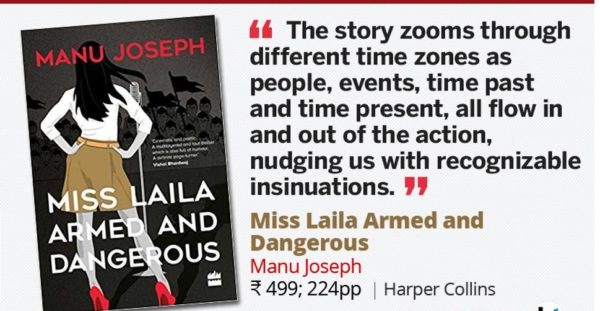

From this point on the story zooms through different time zones as people, events, time past and time present, all flow in and out of the action, nudging us with recognizable insinuations. An enigmatic Damodharbhai, a “beautiful glowing man with a silver beard and a fifty-six inch chest” hovers over the pages in absentia as another labyrinthine sub-plot is set in motion in which a couple ostensibly bound on a terror mission in a blue Indica are tailed by an Intelligence Bureau minion. The virginal Mukundan has never known love and is intrigued by the couple, imagining diverse possibilities as he shadows them. Are Laila and Jamal really part of something sinister? Escaping lovers? Are they merely off on an innocuous business trip? Let down by his own Bureau which unbeknownst to him is in cohorts with the Beard Squad, “the gang of psychotics in Ahmedabad’s Crime Branch”, Mukundan watches helplessly as said Beard Squad arrives on the scene and a shower of bullets sends Laila and Jamal to the hereafter.

One can’t but note the resemblance to a certain dubious encounter or the uncomfortable echoes of news bulletins, talk shows, or the unconvincing “official” version which projects the young, ebullient Laila as “Armed And Dangerous” in much the same way it had her real life counterpart. All this happens in tandem with the other sub-plot being played out in the by-lanes of Prabhadevi, where Miss Iyer crawls forwards and backwards through an underground tunnel, communicating with the mystery survivor and conveying his mumblings to the authorities. In yet another diversion, a nationalistic “Patriarch” remains glued to Miss Iyer’s high-volume videos. Her gamut is endless: Arundhati Roy, P. Sainath, Mukesh Ambani, Irom Sharmila, and even how she had sent her milkman to pay twenty rupees at the local shakha and bought herself a membership of the misogynistic Sangh because she totally qualified, being unmarried, lately celibate and a “badass cultural guardian”. Clueless as to what badass means, the Patriarch even begins to find a mutual parity in their conflicting worldviews: “A patriarch and a modern young woman are natural foes, yet Miss Iyer and he see something in the goodness syndicate that most people cannot. They can see a feudal system where the strong use the weak to attack the stronger.”

The mounting suspense, biting humour, comic irony, fact, and fiction on this rollercoaster ride merge together when the sum of the parts is finally disclosed. Manu Joseph’s daredevilry is unstoppable but he goes to the heart of the matter at the end of the novel where we discover that the survivor’s terrible secrets, the “conversations and phone records that implicate Black Beard and the Beard Squad in six sets of murders involving thirteen people” remain unrevealed despite the inexhaustible Miss Iyer’s efforts. For he knows what “the intellectuals do not understand”, that for the Beards to be taken to justice, Damodarbhai has to fall. And so he awaits that moment when the people will “fall out of love” with their “minor god…tire of him, hate him…To go to war with him when he is at his peak is to go to war against a sacred hologram beamed by the people.”

Though the book has been variously described, as a thriller, as post-plot, post-narrative, bombastic even, it remains rooted in the divine comedy of the here and now, using relatable events and situations as a launching pad, keeping the focus on the real while twisting it just enough to metamorphose it into fiction. This is why “chiller” is the word that comes to mind at the end. What stays with one eventually is the pity of it all: not just the whole messed-up Babel of voices, emotions, the vigilantism and demagoguery of bigotry and hate, but little Aisha musing on their fate as she waits for her older sister Laila’s promised call, bereaved parents falling prey to the growing narrative of their children’s complicity in a terror plot, and a building collapse that is bizarrely relevant at a time when the mind-boggling Kamala Mills inferno has rung down the curtain on the series of man-made disasters that marked the city’s calendar this past year.

Leave a reply