There’s a growing number of dairy farms where the cows are milked with minimal input from humans. Is this the future of dairy farming?

Earlier this year, listeners of The Archers tuned in to hear an internal family debate – about whether to make the switch to robot milking parlours.

About 5% of UK farms already use robotic milking, according to Liz Snaith of the Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers. But they also constitute about 30% of all new milking systems being purchased.

Cows on such farms are essentially free to walk into one of the milking robots’ holding areas at any point of the day – except for the occasional queue.

Once inside, they’re identified by their tags. If the cow’s been milked too recently, an electronic gate leads it out. But if not, its udders are brushed and cleaned before a laser pinpoints exactly where to clamp the milk pumps, adjusting its grip to be as gentle as possible.

Higher milk yields and lower workforce costs are two driving factors for farmers adopting robotic milking, says Ian Ohnstad, director of the Dairy Group and a specialist in milking technology. But other farmers place higher value on other benefits, he says, such as a more flexible working day or more time available for more general work on the herd.

Traditional dairy farmers typically milk cows twice a day using automatic pumps that have to be manually attached – a time-consuming process.

The milking robots allow some cows to enter as many as four or five times a day, driven by the prospect of relieving the pressure of milk in their udders, as well as eating while they’re milked.

Even at the typical daily average of 2.8 times, the overall amount of milk produced is higher, says Ohnstad.

Blackburn-based farmer Chris Bargh, who bought three Merlin milking machines for his 180 cows six years ago, estimates his yield has gone up 8-12%.

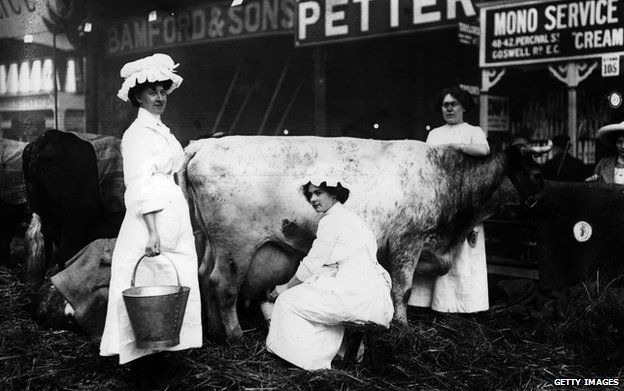

Olden days milking

Bargh says that allowing the cows to be milked more often is better for their health and wellbeing. “If you were only allowed to go to the toilet twice a day it would cause considerable pain,” he says. He says the cows are smart enough to join the shortest queues for the robots.

“It makes the cows so much more relaxed and you see [their] characters come out,” he says, “because it’s not such a mad rush to parlour. It’s like us going on the road during rush hour time [compared with] driving on a nice country road.”

But Ohnstad dismisses any major welfare differences. “They do tend to be quieter, but in terms of welfare I don’t think there’s measurable benefit over conventional milking,” he says.

Of course, some animal activists would argue that neither method is sufficiently humane.

Many dairy farmers remain sceptical for other reasons. For the numerous farmers struggling with the plunging price of milk, the cost is still prohibitive – particularly the initial outlay, Ohnstad says.

A Merlin2 by Fullwood costs about £80,000. A VMS by De Laval costs about £100,000. An Automatic4 by Dutch company Lely costs about £130,000. And those prices don’t even include the annual running costs for machines that run 24/7.

The fact that each machine is typically capable of milking 50 or 60 cows a day also makes robots quite a “lumpy” investment, explains Ohnstad, in that farmers have to increase their herd by those large increments to justify their investment.

Robotic milking has been available commercially in the UK since 1994 but it’s taken a while to get going.

“The technology has moved on tremendously in the last 10 years,” Ohnstad says. “The systems are now very reliable [and] efficient.”

And the data that these robots can collect is staggering, says Bargh, reeling off various possible stats to be gleaned from the robot’s computers, from protein-fat ratio in the milk to white blood cell counts. “It’s the tip of the iceberg,” he says.

But Ohnstad points out that much the same is true of any manual milking parlour these days.

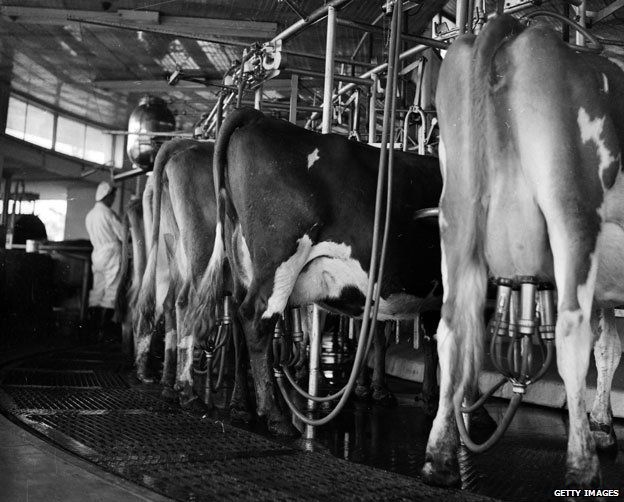

16 July 1956: A row of cows being milked automatically by the new Rotolactor, an Australian invention which enables 300 animals to be milked per hour.

The Rotolactor in 1956 – one of the first machines to milk numerous cows at once

There’s another obstacle to the rise of the milk robot, one that strikes more at the philosophical or sentimental heart of cow farming – proximity to the cows themselves.

“If you look at the driving motivation of many dairy farmers, part of the job that they enjoy is the contact with the cows,” Ohnstad says. “But with robotic milking – the actual milk extraction process becomes a background activity.”

“[Robotic farming] is a version of the future,” Ohnstad says, “not the solution for every dairy farmer.”

Bargh agrees, although he argues that farmers who love milking cows are actually better suited to robots. Each farmer with a robotic system still needs to be constantly overseeing the herd and engaged with the cows.

“It makes good cowmen better and bad cowmen worse,” says Bargh.

Leave a reply