Addressing youths in the north of Paris during the 2012 presidential campaign, François Hollande declared that, if elected, he wanted to be judged by one objective. “Will young people be better off in 2017 than in 2012?” His bold challenge helped draw a solid majority of the youth vote (62% of the 25-24 year range), but it would soon become a bitter indictment of his presidency.

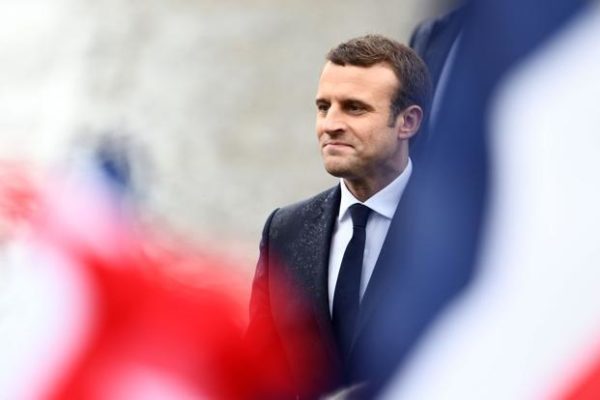

Emmanuel Macron, his successor who was inaugurated Sunday, promised his own Camelot-style renewal. But Macron’s youth vote was disappointingly low for a figure who styled himself as a usurper and who will be France’s youngest president ever. And much of the vote he did capture may have been more attributable to a dislike of the anti-Europe Marine Le Pen than an embrace of Macron’s message. How that youth vote broke down is a pretty good proxy for the country’s main divisions and an indicator of the enormous challenge ahead.

Far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon did better than Le Pen among the 18-24 age group in the first round; in part this was because of the Bernie Sanders-like appeal of his socialist economic message and in part because many young people were repelled by Le Pen’s pledge to take France out of the euro. In the second round of voting, the older the voter, the more likely he or she was to vote for Le Pen, so that seems good for Macron. However, Le Pen still received 40% of 25-34- year-old vote; that must be seen as a cry of desperation from an age cohort that is old enough to be realistic about its prospects.

Politically, young people tend to veer between apathy and radicalism. When they bother to vote at all, young people in America and Britain have largely stuck together recently. In Britain, they voted overwhelmingly to remain in the European Union, 75 to 25% for the 18 -24-year-old age group. In the US presidential election, 55% of voters under 30 voted Democrat, down from 60% in 2012. Donald Trump got 37% of the youth vote.

But this election was essentially a tale of two youth populations in France: those who have options in life and those who despair. Around a quarter of French aged 18 -24 are unemployed, more than double the overall unemployment rate. France’s balkanized labour market—where the lucky have iron-clad “permanent” contracts but a growing number have part-time or temporary work—hits the young hard. The average age for obtaining the first permanent work contract rose to 28 in 2016 from 22 in 1992.

Education also lets down the young. France has a rigorous selection system. Those who land in good schools and make it through the early stages go on an academic track, followed by jobs in the private sector or, as likely in a county where one in five workers is employed by the state, government. But it is brutal on those who fall by the wayside, as the brilliant 2013 book La Machine à Trier (or the sorting machine) explained. Some 20% of primary school students fail to acquire adequate mastery of basic literacy and numeracy skills, and drop-out rates are too high. Polls show the French pessimistic about their education system and how well it prepares students for the world of work.

Apprenticeship programmes have increasingly been a route to skills and employability in Germany, Austria, the UK and elsewhere. But France’s apprenticeship system is excessively centralized and mind-numbingly complex, and seems to serve best only those who don’t need the positions to succeed. In a paper for the French Council of Economic Analysis, Pierre Cahuc and Marc Ferracci noted that while enrolment numbers for apprenticeships rose between 1992 and 2013, the rise came almost solely from those with higher levels of qualifications, while the proportion of apprentices without prior qualifications fell to 35% from 60%.

But inequality in France looks a lot less stark than in many other countries, including the US. That is true but also deceptive because the country has very low levels of social mobility, more in line with the rates in the US or the UK than the Scandinavian social democracies to which it is often compared. Parental earnings are a depressingly good indicator of an offspring’s prospects.

The barriers to social mobility, particularly education but also the labour market and even the structure of public housing, will continue to drive frustrated voters to Le Pen’s National Front if nothing changes. And the National Front may get better at attracting them.

Shortly before the first round of voting, I visited the leader of the National Front’s highly organized youth movement. With his prep-school polish and quiet confidence, 23-year-old Gaëtan Dussausaye, a former philosophy student, seemed an unlikely poster boy for Le Pen’s movement. He said that the National Front has many supporters like him. Many have made it through the selection machine that is France’s education system or found employment, but came from humbler roots and see the system as fundamentally flawed.

The National Front’s fundamental devotion to its populist cause would not be changed of an electoral defeat, he was convinced. “We in the National Front don’t seek to serve the markets,” he said. “We just want to serve the people.” To Dussausaye and his cohort in the movement, Macron is not a reformer. They will be looking for ways to do to the new president what voters did to the party of Hollande. So will Mélenchon, who remains popular among the young.

And yet young people are nothing if not changeable. Maybe they can be wooed back to the mainstream. But it will take actions this time, not just words.

Leave a reply