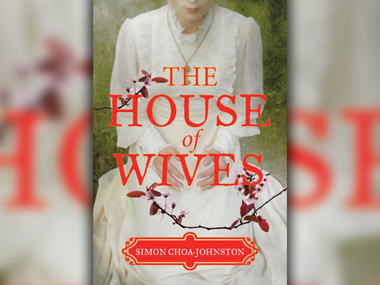

From the very premise of time, which has been treated to some lengthy consideration in the form of Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy, comes The House of Wives by Canadian author Simon Choa-Johnston. Firstly, comparing the book to the sizeable body of work that Ghosh already has out there would be unfair unless it is taken as an aperitif for this journey. Johnston’s book is a labour of love, as his attempts to trace the roots of his family led him to write the book. What began as a play, Johnston claims, turned into a novel, as most fictional elements slowly fell into place. That said, even the most blasé detail about his ancestry that can be verified is not without its tinge of fictional romance and disbelief.

The book opens in 1860 Calcutta, where our lead character Emanuel Belilios – also Johnston’s great grandfather – is a young Sephardic Jew looking to make his mark in the business-side Calcutta, populated by a handful of other Jewish competitors and families. Emanuel, keen to prove his business mettle to his doubting father, sets out to establish an empire pillared on the opium trade (Patna AAA grade Opium – apparently the best Opium in the world) that flourishes between the port city and Hong Kong, China.

The first half of the book — which deals with Emanuel’s rise with unsparing, uncompromising instinct to pull him through tricky deals and situations — is perhaps the most exciting part of the book. The pace with which his meteoric rise is narrated, from the view of his depthless regard for most things emotional, is intoxicating in a way not most stories are; stories that usually dovetail the paths of those who rise from the lesser levels of society or businesses. Instead Emanuel, here, belongs to a wealthy family, but his ambitions still sizzle with the fire of doubt with which his father considers his manhood.

Emanuel marries Semah, the daughter of a non-Jewish wealthy family, more for want of a dowry than the need for a companion. Semah is physically challenged and initially feels indebted to her husband for having married her. The marriage, and its expected uneasiness aside, Emanuel’s conquests continue apace, and make for a riveting read with auctions, 50-50 decisions and seemingly inspired improvisations.

In the second part of the book, the story moves to Hong Kong. Here, perhaps, appears the best writing and descriptive analysis of the text with the audacious scale and grandeur of the opium trade in China written in full. The prospects, the dangers and the challenges all make for a heady mix of adventure and risk that Emanuel must, and does eventually, undertake. In Hong Kong, Emanuel meets the daughter of his partner, the much younger Chinese woman, Pearl whom he takes as his second wife – and so begins the final part which gave the book its name.

Semah refuses to accept Emanuel’s request for a divorce, and arrives unannounced in Hong Kong where he is already living with his new wife Pearl, in an exorbitantly royal mansion, aptly called Kingsclere (the property actually existed and was inhabited by Johnston’s great grandfather as he later tells us in a note). While Emanuel’s business acumen rings large over his character, and Semah’s nervous energy is palpable, it is difficult to estimate what goes on in the mind of the youngest of the three characters. Pearl, though self-assured and buoyant, feels like an incomplete picture. Upon the arrival of the first wife, her character recedes into being flat, and oddly, predictable, unlike before. The reservation, particularly, from peeling the layers of her character and choices renders her a bit trivial. For that matter, once the two wives start living together, the books moves at a toppling pace. Often you are left to wonder the whys and hows and it would have served the narrative better if the author delved deeper into the mindsets of two women living together as wives of the same man – the peculiar comedy of the situation thus not advantaged upon in full.

This final part of the book is also strangely, thinnest in terms of emotional detail. Things move quickly and at times the pace eats into the depth the worming narrative could have done with. In the quest to attain bragging rights in this derby of sorts, the two wives quarrel, make up, and then quarrel again. Emanuel’s role diminishes as the book moves on. The two wives have children, who grow up, and bring them closer, before an unforeseen tragedy strikes the household leaving all involved in a state of breakdown. The book ends with the shutterbug moment that romantic reprises are made of, and feels like an un-caging of a number of questions that have lingered in the air. That said, not all of them, or even most of them are answered.

A thing that has to be said about the book is the quality of Johnston’s prose. It is immaculate, and safely treads the line between simplistic and poetic. Johnston writes, it seems, with ease and to his credit manages to infuse that lightness in a text that manages to intrigue without relying heavily on the use of the metaphor. The House of Wives is engaging, and for its first two parts, exhilarating in the least. If not for the surface phenomenon of its characters, most notably the young Pearl, it would hold its ground in popular as well as classical fiction. It is a breezy read nonetheless, unique in its plot which despite its limitations of a familiar setting, delivers nuance admirably.

Leave a reply