Now, it seems to me that all those who are against the party system and who must be taken also on that very account to be against opposition, seem completely to misunderstand what democracy means. What does democracy mean? I am not defining it. I am asking a functional question. It seems to me that democracy means a veto of power. Democracy is a contradiction of hereditary authority or autocratic authority. Democracy means that at some stage somewhere there must be a veto on the authority of those who are ruling the country.

In autocracy there is no veto. The king, once elected, is there with his inherent or divine right to rule. He does not have to go before his subject at the end of every five years to ask them, ‘Do you think I am a good man? Do you think I have done well during the last five years? If so, will you re-elect me?’ There is no veto on the part of anybody on the power of the king. But in democracy we have provided that at every five years those who are in authority must go to the people and ask whether in the opinion of the people they are well qualified to be entrusted with power and authority to look after their interest, to mould their destiny, to defend them. That is what I call veto.

Now, a democracy is not satisfied with a quinquennial veto that the government should go at the end of five years only to the people and in the meantime there should be nobody to question the authority of the government. Democracy requires that not only the government should be subject to the veto, long-term veto of five years, at the hands of the people, but there must be an immediate veto. There must be people in the Parliament immediately ready there and then to challenge the government.

Now, if you understand what I am saying, democracy means that nobody has any perpetual authority to rule, but that rule is subject to sanction by the people and can be challenged in the House itself. You will see how important it is to have an opposition. Opposition means that the government is always on the anvil. The government must justify every act that it does to those of the people who do not belong to its party.

Unfortunately, in our country all our newspapers, for one reason or other, I believe it is the revenue from advertisements, have given far more publicity to the government than to the opposition, because you cannot get any revenue from the opposition. They get revenue from the government and you find columns after columns of speeches reeled out by members of the ruling party in the daily newspapers and the speeches made by the opposition are probably put somewhere on the last page in the last column. I am not criticizing what is democracy. I am saying what is the condition precedent for a democracy. The opposition is a condition precedent for democracy.

*****

But what we forget is that we have a Constitution which contains legal provisions, only a skeleton. The flesh of that skeleton is to be found in what we call constitutional morality. However, in England it is called the conventions of the Constitution and people must be ready to observe the rules of the game.

Let me give you one or two illustrations which come to my mind at this moment. You remember when the thirteen American colonies rebelled, their leader was [George] Washington. It is really a very inadequate way of defining his position in the American life of that day merely to say that he was a leader. To the American people, Washington was God. If you read his life and history, he was made the first president of the United States after the Constitution was drafted. After his term was over, what happened? He refused to stand for the second time. I have not the least doubt in my mind that if Washington had stood ten times one after the other for the presidentship, he would have been elected unanimously without a rival. But he stepped down the second time. When he was asked why, he said,

“My dear people, you have forgotten the purpose for which we made this Constitution. We made this Constitution because we did not want a hereditary monarchy and we did not want a hereditary ruler or a dictator. If after abandoning and swerving away from the allegiance of the English king, you come to this country and stick to worship me year after year and term after term, what happens to your principles? Can you say that you have rightly rebelled against the authority of the English king when you are substituting me in his place?”

He said, ‘Even if your royalty and fidelity to me compels you to plead that I should stand a second time, I, as one who enunciated that principle that we should not have hereditary authority, must not fall a prey to your emotion.’ Ultimately, they prevailed upon him to stand at least a second time. And he did. And the third time when they approached him, he spurned them.

Let me give you another illustration. You know Windsor Edward the VIII whose serial story has now been published in the Times of India. I had gone to the Round Table Conference and there was a great controversy going on there as to whether the king should be allowed to marry the woman whom he wanted to marry, especially when he was prepared to marry her in a morganatic marriage, so that she may not be a queen, or whether the British people should deny him even that personal right and force him to abdicate. Mr Baldwin was of course against the king’s marriage. He would not allow him, and said, ‘If you do not listen to me, you will have to go.’

Our friend Mr Churchill was the friend of Edward the VIII and was encouraging him. At that time the Labour Party was in the opposition. They had no majority and I remember very well the Labour Party people considered whether they could not make capital out of this issue and defeat Mr Baldwin, because there was a large number of conservatives who in their loyalty wanted to support the King, and I remember the late Prof. Laski writing a series of articles in the Herald condemning any such move on the part of the Labour Party.

He said, ‘By our convention we have always agreed that the king must accept the advice of the prime minister and if he does not accept the advice of the prime minister, the prime minister shall force his ejection. That being our convention, it would be wrong on our part to defeat Mr Baldwin, on an issue which increases the authority of the king.’

And the Labour Party listened to his advice and did nothing of the kind. They said, they must observe the rules of the game. If you read English history, you will find many such illustrations where the party leaders have had before them many temptations to do wrong to their opponents in office or in opposition by clutching at an issue which gave them temporary power, but which they refused to fall a prey to, because they knew that they would damage the Constitution and damage democracy.

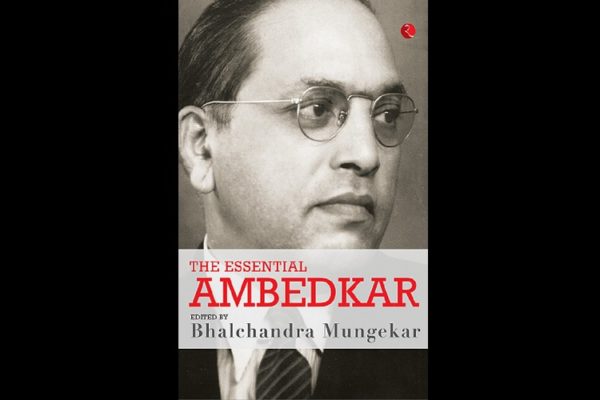

Excerpted with the permission of Rupa Publications from “The Essential Ambedkar” edited by Bhalchandra Mungekar.

Leave a reply